Post Disaster Consolidation of Land, Memory and

Identity

Walter Timo DE VRIES, GERMANY

1)

This peer reviewed paper was presented at the FIG Working Week in

Christchurch, New Zealand, 2-6 May 2016. This paper takes a closer look

at the post-disaster re-development plan for urban areas, with a

particular focus on reconsolidating historical social memory and

preservation of identity. This is done using two well-documented cases

of urban disasters: the firework disaster in Enschede/Netherlands in

2000 and the Merapi disaster in Yogyakarta / Indonesia 2010

SUMMARY

Disasters in cities contain severe destruction of buildings and loss

of access to land. Consequently, a post-disaster re-development plan may

need to rely on different land consolidation approaches. An associated

dilemma is to re-establish the built-up area in its original formal

shape, or to innovate the urban design partially or completely. An

important consideration in the allocation of new land and building

rights is whether to restitute former rights or allocate new rights.

Participation of former residents and firm owners alongside overcoming

the immense social trauma are crucial elements of this process.

The aim is to derive new land consolidation optimization criteria

which could support urban post disaster land consolidation. The guiding

hypothesis hereby is that consolidation of memory and identity are two

important aspects which need to be incorporated in land consolidation

design and implementation procedures in order to ensure ownership of the

consolidation result and to help overcoming the social trauma.

Land consolidation theory has primarily been rooted in agricultural

economics and land management. The concept of optimization during the

consolidation processes can however be critically questioned from the

perspective of social disaster mitigation experiences. In this body of

literature it is argued that the return to daily life after a disaster

requires both a sufficient acknowledgement that humans tend to want to

re-install historically known artefacts in order to be able to

reintegrate into regular new social routines. This is summarized by the

concepts of memory consolidation and preservation of identity. These

concepts provide an analytical way to question contemporary urban land

consolidation approaches.

Two relatively recent specific cases were used to assess the degree

to which elements of memory consolidation and identity preservation are

incorporated in post disaster land consolidation: the firework disaster

in Enschede, Netherlands in 2000, and the Merapi disaster in Yogjakarta,

Indonesia in 2010. These cases were chosen because sufficient

documentation has been collected, and it was still possible to acquire

additional data from people who had experienced both the previous and

post disaster situation.

Both cases exhibited considerable attention for the simultaneous

processes of reconstruction and participation in the land consolidation

processes. Participation is often framed as a process which has to be

stimulated during a technical land consolidation and reconstruction

process. In some instances it is however an endogenous social process

whereby citizens claim ownership of the process prior to the technical

reconstruction. Especially in the resurrection of historical monuments

and/-or in the delineation of areas with spatial significance in

relation to the disasters.

Where conventional consolidation approaches in rural areas tend to

emphasize the need to optimize agricultural production or environmental

protection, optimization indicators in post disaster consolidation need

to be adapted. Especially procedures and tools to incorporate memory

consolidation and identity preservation need to be incorporated. This

can be done theoretically, but still requires further research and

actual implementation experiences into how to consolidate that into

current institutional procedures and operational software packages.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the past 15 years there have been an increasing number of urban

disasters, the most prominent ones being the 2011 earthquake in

Christchurch / New Zealand, 2011 earthquake and Tsunami affecting

various urban centres in Japan, the 2010 earthquake affecting

Port-au-Prince in Haiti and the 2004 south East Asian Tsunami affecting

Banda Aceh amongst others. A disaster is ‘a sudden, calamitous event

that seriously disrupts the functioning of a community or society and

causes human, material, and economic or environmental losses’ (IFRC) .

Besides the natural disasters there is also an increase in mand-made

disasters, usually due to an increase in traditional hazards such as

fires and explosions, or due to human conflicts, terrorism, war, human

errors, irresponsible settlement or mismanagement in planning. Both

natural and man-made disasters manifest themselves with loss of lives

and usually severe loss of buildings. Sustainable reconstruction after

disasters takes place when the immediate threat of the disaster event

has disappeared. In this phase there is an urgent need to rehabilitate

livelihoods, reconstruct buildings and infrastructure and (re-) allocate

land and building rights. Here, spatial planners, land managers,

architects and civil engineers play a crucial role.

For both types of disaster a key characteristic of urban disasters is

that they - besides the loss of lives and severe destruction of

buildings - are accompanied a loss of access to land and real estate

property. In the process of reconstruction, a post-disaster

re-development plan may needs to rely on different land consolidation

approaches. Not only may previous owners and occupants of land and

buildings have died as a result of the disaster or do the buildings no

longer exist (as a result of which reallocation of ownership may be

necessary), also the entire infrastructure may prevent the immediate

reconstruction of the area in exactly the same shape. A reconstruction

dilemma is therefore to re-establish the built-up area in its original

formal shape, or to innovate the urban design partially or completely.

An important consideration in the allocation of new land and building

rights is whether to restitute former rights or allocate new rights.

Participation of former residents and firm owners alongside overcoming

the immense social trauma are crucial elements of this process. In other

words, land consolidation and reconstructing property should not only

cater for the administrative process, but also take the social

reconsolidation into account. This article takes a closer look at what

this consist of, with a particular focus on reconsolidating historical

social memory and preservation of identity. This is done using two

well-documented cases of urban disasters: the firework disaster in

Enschede/Netherlands in 2000 and the Merapi disaster in Yogyakarta /

Indonesia 2010. In these cases the degree to which elements of memory

consolidation and identity preservation are incorporated in post

disaster land consolidation are assessed.

2. URBAN LAND CONSOLIDATION

The conventional association of the scope and utilization of land

consolidation is with agricultural economics and rural development. FAO

(2003) refer to land consolidation as Land consolidation can assist

farmers to amalgamate their fragmented parcels. For example, a farmer

who owns one hectare divided into five parcels may benefit from a

consolidation scheme which results in a single parcel. In many eastern

European (FAO, 2004) and African land consolidation programs tend to

have primarily such an economic production (Musahara, Nyamulinda,

Bizimana, & Niyonzima, 2014) and/or and rural development focus

(Bullard, 2007). Musahara et al. (2014) describes this micro-economic

agrcultural benefit in the cases of Rwanda, where the Land Use

Consolidation (LUC) programme was initiated in 2008 as part of a broader

Crop Intensification Programme in Rwanda launched earlier in 2007.

More recently land consolidation is associated specifically to a

societal benefit or public value, such as food security (Bennett, Yimer,

& Lemmen, 2015) or environmental protection (Louwsma et al., 2014). Not

the micro-economic agricultural production values count in these cases,

but the public values at a larger – often national or regional - scale.

The optimal output of a land consolidation process then needs to be

evaluated in terms of this societal benefit, rather than a pure economic

benefit.

Method-wise, Louwsma and Lemmen (2015) introduce land consolidation

as an instrument to counteract land fragmentation and the associated

negative impact on the productivity and costs of farming. The most

common interpretation of land fragmentation relates to physical aspects

of fragmentation, i.e. holdings with a large number of small parcels

scattered over a considerable area. (Savoiu, Lemmen, & Savoiu, 2015)

indicate that different types of land consolidation exist which each

require different methodologies of implementation and different

indicators of optimization. Vitikainen (2004) specifies such indicators

of land consolidation are (Vitikainen, 2004): defragmentation of parcel

size and location (improvement of agricultural and/or forest land

division, re-allotment of leasehold areas, enlargement of farm size),

reconstruction of urban areas (land use planning in village areas,

readjustment of building land), creation of accessibility to roads and

utilities (improvement of road network, drainage network), environmental

protection and planning (implementation of environment and nature

conservation areas), spatial and regional development (promotion of

regional development). Demetriou, See, and Stillwell (2013) further

specify procedures and decision support systems to quantify the

resultant optimization parcel sizes.

Louwsma and Lemmen (2015) acknowledge that there are multiple

socio-economic dimensions of fragmentation. Participation and embedding

of economic, technical informational and infrastructural solutions in a

societal context is considered of crucial importance (Louwsma, Van Beek,

& Hoeve, 2014). Especially in urban disasters parcel fragmentation is

however not the key problem when reconstructing and returning to daily

life. Moreover, also the methods, processes and key indicators used on

rural land consolidation do not seem to fit the objectives of urban land

consolidation. Plot size, land value are not the primary elements, but

rather public value, participation, resilience and public acceptance.

Furthermore, in urban areas there is a different sense of neighborhood

and spatial identity.

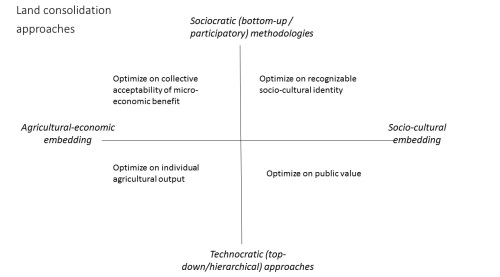

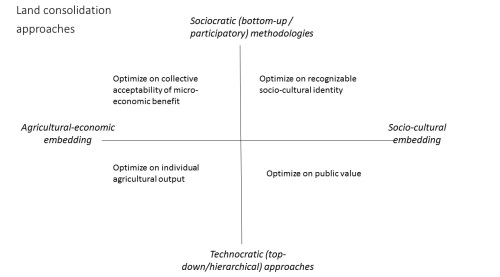

Based on the above considerations, Figure 1 summarizes the land

consolidation approaches and its optimization criteria relevant for the

consolidation tools and instruments. The traditional land consolidation

optimizes on economic productivity or collective micro-economic benefit.

When emphasizing socio-cultural embedding, optimizing public values

become more important. Real participation in all steps of a land

consolidation process, including participating on which values are

crucial for the stakeholders, optimize on criteria which are

recognizable and identifiable by stakeholders.

Figure 1. Summary of land consolidation

approaches and optimization criteria

3. MEMORY AND IDENTITY

The analytical framework to evaluate this documentation relied on the

conceptualization of post-disaster ’memory’ by Bevan (2006) and urban

cultural identity by (Boom, 2009). Although Bevan (2006) primarily

focuses on the deliberate (instead of accidental) destruction of

cultural heritage during man-made disasters, such as war times and

terrorists attack, implicitly he conceptualizes cultural memory from an

extensive description of symbolic meanings which are manifested in

specific buildings, locations and infrastructure. The Twin Towers attack

on 11 September 2011 indeed destroyed 110 floors of two prominent

buildings, but essentially the symbolic value of that physical

destruction was related to a difference in historically grown and

accepted cultural and societal values. Similarly, the 1993 destruction

of Stari Most bridge in Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina during the Balkan war

and the more recent destruction of world heritage site Hatra in Mosul,

Iraq, in the contemporary war of Islamic State is primarily meant to

destroy collective memory and spatial-physical anchor points of societal

fabric. Both were symbols and meeting point of a multicultural and

cosmopolitan society, with ethnically mixed marriages and religious

diversity. The destruction of the physical artefacts was an immediate

statement against such cultural values and identities.

As cultural identity and collective memory depend on imitating and

prolonging traditions on the one hand and physical recollection of the

past or personal linkages from the present to the past, reconstructing

artefacts with the aim to restore previously existing values needs to

make both a physical and symbolic connection to the past. The simplest

way is imitation of the past. Architectural building imitations rely on

procedures and methods to re-erect the buildings and artefacts in the

exactly the same shape as before. Many cities after the Second World War

were reconstructed in this way. Although this did result in some degree

of cultural memory reconstruction, it became also clear that the

buildings lost value in authenticity, because they were no longer

original and could no longer be identified with the building labour of

the past (Denslagen & Gutschow, 2005).

Instead of exact imitation which is primarily based on the physical

artefacts, it is also possible to rely on the personal memories and

values of the people involved. Monuments, for example, are one way to

prolong the collective memory of people, rather than to bring back the

buildings of the past. In line with this reasoning, land ownership

imitations could be one way to complement the cultural memory

reconstruction. This is where land consolidation touches memory

consolidation. Symbolic land consolidation is then more related to

common land artefacts which have some public significance, such as

historical sites or parcels of land or buildings with significant value

to local communities. Such values can often not be recognized by

physical objects, but only be identified by extensive discussions with

local representatives of both the past and the future.

4. URBAN DISASTER CASES

Two urban disaster cases were identified for this research, which

were different in location, size, impact and origin of disaster. Similar

was however that land consolidation took place, and that this process

was relatively well documented. The 2000 firework disaster in a

residential area, Roombeek in Enschede, in the east of the Netherlands

near the German border on 13 May 2000. The blast had destroyed 400 homes

and damaged 1500 buildings of the residential area. The documentation of

this case is largely based on the documentation aggregated by the

dedicated websites http://www.roombeek.nl,

http://www.enschede-stad.nl/projecten.php?project=Roombeek , and the

theses of de Groot (2005), Langereis (2014). The second case concerns

the Merapi volcanic disaster in Yogyakarta / Indonesia which took place

in October-November 2010. Over 350,000 people were evacuated from the

affected area. The volcanic material from the eruption overflowed the

river running through the province of Yogyakarta, inundating hundreds of

houses along the riverbank. After the mudflow subsided, people returned

to their homes, and reconstruction started, yet the area remains prone

to the next disaster if not accompanied by proper planning and land

management. Land consolidaiton is an important part of this. The data of

this case are largely based on the documentation and reports of the

provincial office of Yogyakarta of the Indonesian land agency BPN (BPN

Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, 2014).

4.1 Land consolidation after Firework disaster Enschede,

Netherlands, 2000

The reconstruction and consolidation of the Roombeek area employed

new methods of spatial planning and management, allowed many architects

to design individual houses and relied on new urban consolidation

methods. In other words, the disaster also opened up new ways of

reconstruction and reconsolidation. The boundary of area Roombeek in

Enschede is closely related to recent history. Being originally an area

of textile factories, the area consisted of a mix of working class

houses, factory areas, small parks, middle class residential areas and

estates of textile factory owners. This mix of land use and economic

activity explains why it was possible that a firework storage resided in

the area. However on the fatal day of the disaster 177 ton of firework

exploded after a chain reaction of smaller explosions. It wiped out an

area of 42,5 hectare (the approximate size of the Vatican city),

affected 650 houses, 500 small sized enterprise buildings and 8

associations residing in buildings. A total of 23 people were killed,

whilst approximately 950 people got injured.

The reconstruction of the area was subcontracted to a specific

project bureau ‘Projectbureau Wederopbouw Roombeek’ (PWR) under the

supervision of the urban designer Pi de Bruijn. In addition to the new

urban design, and information and advisory centre (IAC) was established

with the aim to help victims cope with the traumatic experiences and

support them with information needs and psychological help.

Furthermore, a foundation city recuperation (SSE) was established to

make an inventory of the damage to houses and property. Both IAC and

SSE currently no longer exist, but they played a pivotal role in the

reconstruction alongside the PWR.

The process of reconstruction had one central objective:

participation. Members of the PWR visited victims and discussed requests

and needs during and after reconstruction. This resulted in a collation

of 3000 opinions and ideas to reconstruct the new area Roombeek. The

objectives included:

-

Maintain the area as a specific quarter with its own

characteristics, especially the mixed types of social and economic

activity and socio-economic backgrounds

-

Ensure the possibility for all previous residents and small

enterprises to return to the area

-

Maintain part of the original layout of the area

-

Maintain or reconstruct old industrial buildings and restore the

industrial heritage

-

Ensure that the area has an economic future

-

Interconnect the area as closely as possible with surrounding areas

/ quarters

-

Support autonomy of the area in terms of development and economic

activity

These objectives led to a reconstruction and consolidation plan in

which diversity and multi-functionality were key and preservation of

both cultural and economic identity was important. The reconstruction

plan included:

- 1500 houses of which 150 were renovated

- An area for 4000 residents

- 400 private companies – small-sized businesses

- 1200 commercial work places – working from home – were

established

- 4500-8000 m2 of retail

- Studio spaces and room for culture

- Maintenance of industrial heritage (through reconstructing older

factories)

- Close accessibility to neighboring areas through access

corridors

The reconstruction of houses and buildings formed a trend break in

Dutch urban planning practices. Instead of subcontracting all housing to

large real estate developers (thereby ignoring all possibilities of

public participation), the project bureau deliberately opted for

allowing private housing projects (in addition to the social housing).

This allowed people to influence their own working and living

environment with the support and supervision of professional experts.

Parcels were individually re-allocated with a limited number of

conditions. A total of 400 people opted for this possibility and each

created their own style house, which promoted the variety.

The industrial factory remnants were reconstructed into museums, art

schools, studio spaces, small apartments and small office spaces. It

maintained the look and feel of factories, be it that the usage has

changed. This also implied a change of land and building ownership and

use as compared to the previous status.

4.2 Land consolidation after Merapi eruption and subsequent flooding

in Yogyakarta province, Indonesia

The Merapi eruption especially affected areas close to the crater.

Material bursts of Mount Merapi damaged several villages in the region

of Sleman, destroying thousands of homes and affecting ownership of

local residents. To avoid the potential of land conflict the provincial

land agency decided to execute a land consolidation process,

specifically in the local villages surrounding the area of village of

Cangkringan. This process is well-documented in the BPN reports, the

final report being ADDIN EN.CITE BPN Provinsi

Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta20142591(BPN

Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, 2014)2591259127BPN

Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta,

Laporan hasil akhir konsolidasi tanah tahun 2014.3962014Badan

Pertanahan Nasional Republik Indonesia(BPN

Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, 2014). The land consolidation plan

was based on 4 pillars:

- the regional spatial plan, primarily targeting re-establishing

and reconstructing economic activity such as agriculture;

- infrastructure development associated with the handling and

control of disasters;

- local topographical conditions,

- community participation.

After 4 years the reported results included:

- The availability of public facilities and social amenities

without moving the landowner;

- A financing model whereby the land owners profited from land

development;

- Optimization of road and parcel infrastructure;

- Allocation and control of land ownership rights by title

certification.

The spatial plan for the next 20 years also included that it would

not be allowed to live in a residential development area directly

affected eruption Merapi 2010; that it would not be allowed to add new

facilities and infrastructure in the affected areas Direct eruption

2010; and, that land utilization would only be allowed for special

interest tourism, agriculture, plantation and reforestation in areas

directly affected the eruption in 2010.

One of the main reasons why it was possible to find support for these

plans and execute the land consolidation without any major resistance

was the presence of ‘gotong royong’ (mutual aid) among people in a

certain community, which is an Indonesian tradition, rooted in Javanese

culture, to support among others the reconstruction of each other’s

houses.

4.3 Comparative summary of results

Table 1 summarizes and compares the results with regard to different

aspects of the reconstruction:

| Aspects of

reconstruction |

Firework disaster in Enschede

|

Merapi disaster in Yogjakarta

|

| Objectives of

reconstruction |

Preservation of area characteristics,

and support autonomous development |

Land consolidation to avoid potential

for land conflicts |

| Objectives of

reconstruction |

Preservation of area characteristics,

and support autonomous development |

Land consolidation to avoid potential

for land conflicts |

| Key claims of

success and results of reconstruction |

Support autonomy of

the local community in the area of development |

Gotong royong, a Javanese tradition, to

support each other within the community |

| Key claims of

success and results of reconstruction |

Support autonomy of the local community

in the area of development |

Optimization of land management and land

rights distribution alongside sustainable financing model |

Figure 1. Summary of land consolidation

approaches and optimization criteria

Table1. Summary and comparison of results

5. DISCUSSION

Both cases exhibited considerable attention for the simultaneous

processes of reconstruction and participation in the land consolidation

processes. Although participation is a word that is frequented mentioned

in the documentation and success factors in both cases, it is often

framed as a process which has to be stimulated during a technical land

consolidation and reconstruction process. It is a passive participation,

whereby – perhaps formulated a bit black and white, but to make the

point clear - stakeholders either need to be convinced of their possible

benefits of the land consolidation, or stakeholders become gradually

informed of their benefits and rights. The economic perspective of land

consolidation tends to be on the forefront, either in the form of

agricultural productivity or in the form of economic potential of small

businesses. The participation is than considered a dependent factor of

economic optimization rather than the opposite.

At the same time there is however also evidence that the

participation is an endogenous social process whereby citizens claim

ownership of the process prior to the technical reconstruction.

Especially in the resurrection of historical monuments and/-or in the

delineation of areas with spatial significance in relation to the

disasters. This refers to the symbolic consolidation alongside the

physical consolidation. In fact, memory is preserved and optimized

rather than economic value.

A second issue which comes back in both cases is the explicitly

defined objectives to seek long-term security. This security is however

mainly formulated as a perception of security. Feeling comfortable and

feeling security are passive characteristics of such a perception. After

reconstruction these perceptions should be fostered and optimized. More

actively, reconstruction and land consolidation focuses on building

attractiveness. This may seem a vague concept, but it is literally

formulated in both cases as a planning principle. Apparently,

attractiveness is a societal value which can be used as a concept to

bridge shared perceptions to hard planning aims. This type of

optimization indicator is one that often does not appear in most land

consolidation reports or essays.

Finally, for the specific urban context of the Roombeek cultural

historical, architectural and urban design value (in addition to

economic value) is considered important. This requires an insight into

the industrial and constructive elements of buildings, knowledge and

experience with light, usage of visual elements, spatial perception,

functionality of buildings and public spatial element, and the

psychology of the environment. This finding relates both to a cultural

value and a professional value. Such values may not be very explicit,

yet they are recognizable in so-called epistemic communities, i.e.

communities who shared among each other similar values, rules and

traditions. Consolidating epistemic values often does not occur by hard

rules, rather by soft rules or isomorphic behavior. Yet, adhering to

such values and acknowledging such values is crucial for the acceptance

of the technical land consolidation solution.

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Where conventional consolidation approaches in rural areas tend to

emphasize the need to optimize agricultural production or environmental

protection, optimization indicators in post disaster consolidation need

to be adapted. The main reason is that post-disaster consolidation also

needs to take into account how to cope with the social trauma. The

societal context and the social values existing prior and after the

disaster are thereby critical. Socio-cultural embedding, optimizing

public values as well as active participation in all steps of a land

consolidation process, prior, during and after the land consolidation

process are decisive. Consolidation of memory and identity needs to be

enacted alongside realizing the micro economic benefits (of either

agriculture, small-medium businesses or real estate). This requires that

procedures and tools to incorporate memory consolidation and identity

preservation need to be incorporated in both hard legal and technical

instruments and soft methods and tools. This can be done theoretically,

but still requires further research and actual implementation

experiences into how to consolidate that into current institutional

procedures and operational software packages.

REFERENCES

Bennett, R. M., Yimer, F. A., & Lemmen, C. 2015. Toward

Fit-for-Purpose Land Consolidation, Advances in Responsible Land

Administration: 163-182: CRC Press.

Bevan, R. 2006. The destruction of memory: Architecture at war:

Reaktion books.

Boom, S. J. 2009. Roombeek. De vernietiging van cultureel

geheugen en de wederopbouw van culturele identiteit (In English: The

destruction of cultural memory and reconstruction of cultural identity).

Universiteit Utrecht.

BPN Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta. 2014. Laporan hasil akhir

konsolidasi tanah tahun 2014. : 396: Badan Pertanahan Nasional Republik

Indonesia.

Bullard, R. 2007. Land Consolidation and Rural Development.

Papers in Land Management. No. 10: 149.

de Groot, F. 2005. Integrale aanpak-Wederopbouw Roombeek: Erasmus

University.

Demetriou, D., See, L., & Stillwell, J. 2013. A parcel shape

index for use in land consolidation planning. Transactions in GIS,

17(6): 861-882.

Denslagen, W. F., & Gutschow, N. 2005. Architectural imitations:

reproductions and pastiches in East and West: Shaker Publishing.

FAO. 2003. The design of land consolidation pilot projects in

Central and Eastern Europe. In FAO (Ed.): 55.

FAO. 2004. Operations manual for land consolidation pilot projects in

Central and Eastern Europe: 69. Rome: Food and agiculture organization

of the United Nations (FAO).

Langereis, M. 2014. Herontwikkeling van industrieel erfgoed:

vervallen monumenten als aanjager voor vernieuwing. Onderzoek naar

bestuursstijlen van de gemeenten Enschede en Deventer.

Louwsma, M., & Lemmen, C. 2015. Relevance of leased land in

land consolidation, FIG Working week - From wisdom of the ages to the

challenges of the modern world: 15. Sofia, Bulgaria.

Louwsma, M., Van Beek, M., & Hoeve, B. 2014. A new approach:

Participatory Land Consolidation 10. XXV FIG Congress, 16-21 June 2014,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. FIG, 2014. .

Musahara, H., Nyamulinda, B., Bizimana, C., & Niyonzima, T.

2014. Land use consolidation and poverty reduction in Rwanda, 2014 World

Bank Conference on Land and poverty: 28. Washington DC.

Savoiu, C., Lemmen, C., & Savoiu, I. 2015. Systematic Registration in

Romania a New Opportunity for Land Consolidation, FIG Working Week -

From the wisdom of the ages to the challenges of the modern world: 29.

Sofia, Bulgaria. Vitikainen, A. 2004. An overview of land consolidation

in Europe. Nordic jounral of surveying and real estate res

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Prof. dr. ir Walter Timo de Vries,

wt.de-vries@tum.de, is chair

land management at the faculty of civil, geo and environmental

engineering at the Technical University Munich. His research interests

include smart and responsible land management, public sector cooperation

with geoICT and capacity development for land policy. Key themes in his

most recent publications advances in responsible land administration,

mergers of cadastres and land registers, capacity assessment

methodologies for land policy and neocadastres.

CONTACTS

Walter Timo de Vries

Technical University of Munich

Lehrstuhl für Bodenordnung und Landentwicklung / Chair of Land

Management

Department of Civil Geo and Environmental Engineering

Arcisstraße 21, 80333 München GERMANY

Tel. +49 89 289 25799 : mobile : +49 (0) 174 204 1171

wt.de-vries@tum.de

Website: http://www.bole.bgu.tum.de

|