Article of the Month -

December 2013

|

Climate Change and Responsible Governance: The Role of Surveyors in

Assisting Small Island Developing States

John HANNAH, New Zealand

1) This paper was presented

in a plenary session at the Pacific Region Small Island Developing

States Symposium, 18-20 September 2013 in Suva, Fiji. The paper

discuss how surveyors can contribution to the issues of climate change

and responsible governance, particularly as they affect Small Island

Developing States (SIDS). The paper reflects some of the work the FIG

Task Force on Climate Change has been undertaking since it was

established in 2010. John Hannah is chair and at the FIG Congress 2014

in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia the task force will deliver a final report.

ABSTRACT

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) face much

higher vulnerabilities than developed nations. A substantial number of

these vulnerabilities are linked to climate change and involve decisions

over the future best use of land and other resources. The surveyor has a

diverse skill set that can be used to provide the data, the analyses,

the insights and the understanding needed to help make these decisions.

This paper then, which reflects some of the work of the FIG Task Force

on Climate Change, discusses the contribution that surveyors can make to

the issues of climate change and responsible governance, particularly as

they affect SIDS. It begins by outlining the role that the surveyor can

play in climate change and land governance studies and then discusses

the important issues being faced by SIDS. It then draws all these

threads together, making some firm suggestions as to how surveyors can

help SIDS as they grapple with future change. It concludes by noting

that while in recent decades it has perhaps been the profession’s lack

of public profile that has limited the call for such contributions, this

need not be the case in the future.

1. INTRODUCTION

The professional skills that form an essential part

of the surveyor’s tool kit, while not widely appreciated or understood,

are diverse, varied and valuable. In its most recent definition of the

functions of a surveyor, the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

considers that such a person has the, “academic qualifications and the

technical expertise to conduct one or more of the following activities:

-

to determine, measure and represent land,

three-dimensional objects, point-fields and trajectories;

-

to assemble and interpret land and geographically

related information,

-

to use that information for the planning and

efficient administration of the land, the sea and any structures

thereon; and,

-

to conduct research into the above practices and

to develop them” (FIG, 2004).

While these are very broad statements of capability,

they give rise to a practical, pragmatic professional person who

understands spatial measurement, who can represent and interpret spatial

information, who is very competent in the administration and governance

of rights to the land and sea, and who is capable of planning for the

development and use of land. Such a person typically has much of the

technical understanding and many of the skills necessary to exercise

responsible governance over land, being willing to innovate and reform

where necessary. The breadth of professional knowledge and experience in

these issues that surveyors have is an invaluable resource to a world

seeking long-term sustainable solutions to its many and varied land

administration problems.

In addition to finding solutions to

these land administration problems, the surveyor’s expertise in spatial

measurement and analysis allows reliable measurements to be made in

monitoring some of the direct impacts of climate change. For example, it

is the surveyor who measures sea level rise, then links these

measurements to a local reference frame. The surveyor then further links

these to a global reference framework. It is only in such a framework

that the true global impacts of climate change can be understood.

Additionally, it is the surveyor who is able to take a wide variety of

measurement data, transform it into a common reference system and then

integrate it into a Geographic Information System (GIS). The GIS then

becomes a powerful tool for assessing the likely impacts of climate

change on communities (large or small) thus supporting the development

of the mitigation policies needed to protect those communities.

This paper then, which reflects some of the recent work of the FIG Task

Force on Climate Change as well as earlier work done in 2010 (see FIG,

2010), discusses the contribution that surveyors can make to the issues

of climate change and responsible governance, particularly as they

affect Small Island Developing States (SIDS). It begins by outlining the

role that the surveyor can play in climate change and land governance

studies and then discusses the important issues being faced by SIDS.

Finally, it draws all these threads together, making firm

recommendations as to how surveyors can help SIDS as they grapple with

future change.

2. CLIMATE CHANGE – THE ROLE OF THE SURVEYOR

The evidence for present day, human induced climate

change is overwhelming. However, the full extent to which climate is

likely to change in the future (both near term and long term) remains

unclear. Climate models produce a wide range of possible outcomes

depending upon the various forcing factors used – factors that, in turn,

depend upon assumptions relating to industrial growth, greenhouse gas

emissions, deforestation, and human response (amongst other things).

Coping with the resulting environmental change (the 20th ranked issue in

UNEP, 2012) requires the assessment of a wide variety of response

options.

In the same vein, other UN documents (e.g., FAO,

2012) encourage states to have laws, policies, strategies and actions

that are designed to protect the legitimate tenure rights of those

affected by climate change. Such states are encouraged to prepare and

implement strategies and actions to help those displaced by the impacts

of climate change. Similar (but wider) provisions are suggested for

dealing with the effects of natural disasters.

The question may be asked, ”Where do surveyors fit

into this picture?” What particular knowledge does the surveyor have

that can assist the global community as it grapples with its

understanding of the quantum of change and, with it, the various

mitigation or adaptation strategies that may be required? The paragraphs

below seek to answer these questions.

2.1 Measuring and Monitoring Change

The surveyor, by virtue of his/her spatial

measurement skills, is closely involved in monitoring spatial change.

Typically, such change is determined with respect to some coordinate (or

reference) system – a system most likely established by professional

surveyors. It was surveyors, for example, who were responsible for the

definition of the current Fiji Geodetic Datum (1986) [c.f., Hannah and

Maseyk, (1989)].

As with any reference system, its long term stability

(or alternatively, an accurate knowledge of movement in that system with

respect to time), is crucial if the data provided by global monitoring

systems are to be correctly interpreted. For example, best estimates of

global mean sea level (GMSL) change from satellite altimetry indicate a

sea level rise from 1993-2013 of 3.2 ± 0.4 mm/yr compared to in-situ

tide gauge data of 2.8 ± 0.8 mm/yr (Church and White, 2011, 2013). While

this would seem to imply recent acceleration in the rate of rise of mean

sea level (MSL) from its long-term average of 1.8 ± 0.2 mm/yr, no clear

evidence of such acceleration can be detected in the long-term tide

gauge records. Could this discrepancy then, in part, be a reference

system problem?

While the above example highlights issues at the

global level, monitoring issues at the local level are just as important

to climate change studies. It is the local surveyor who is responsible

for providing the high precision measurement link between a tide gauge

and the various bench marks needed to monitor its stability. In New

Zealand, it is the surveying community (in conjunction with others) that

has been at the forefront of the long-term sea level change analyses

that have informed public policy makers on future climate change

scenarios (e.g., Hannah et al, 2010).

2.2 Data Integration and Analysis

In any climate change analysis, “what if” scenarios

form an important part of that analysis. In principle, integration and

analysis of the relevant data needs to precede mitigation and

adaptation. It is the outcome of such analyses that will inform policy

makers if the primary need is one of mitigation or adaptation. Not only

must the spatial data used be in the same reference system (see 2.1,

above), but the spatial analysis tools used for such analyses must be

capable of the necessary analyses. Such tools, which are typically part

of a GIS, are found in the surveyor’s tool kit (e.g., Mardkheh et al,

2012).

2.3 Mitigation and Adaptation

From the surveyor’s spatial perspective, climate

change mitigation measures need to be developed for three primary land

use categories.

2.3.1 Urban Areas/Human Settlements. Here the

surveyor’s professional focus will be upon urban design(so as to

reduce carbon footprint), land tenure issues (so as to address

housing and urban poverty needs), and building orientation (so as to

maximise the use of renewable energy sources). In Italy, for

example, surveyors use their professional skills to assist in

certifying the energy efficiency of both new and renovated

buildings.

2.3.2 Peri-urban Areas. These are areas of rapid

urbanization that are typically heavily influenced by rural-urban

migration. Here there is a need both for spatial planning tools and

for fresh approaches to land tenure issues. De facto urbanization by

squatting is not a long-term, nor a sustainable solution. FIG,

(2010) notes that, “access to land ---- is challenged by a lack of

clearly defined property rights which in turn causes disputes and

resultant instability”.

2.3.3 Rural Areas. These regions are largely

influenced by agriculture, forestry and farming practices. For some

populations, fishing and mineral extraction are important

activities. As urban areas expand (possibly due to climate change

migration) and arable land resources diminish, increasing pressure

will be placed upon the remaining productive land resource. The

surveyor is not only able to use his spatial tools to assess and

analyse the extent and character of climate change impacts, but also

to improve land productivity. In the developed world, precision

agriculture techniques using real-time GPS measurements have been

shown to be able to improve land productivity by more than 30%.

In addition to the above, climate change adaptation

will involve the design and construction of new infrastructure

(particularly in the coastal margins and in flood prone areas), the

re-location of land boundaries (particularly those abutting water

bodies), re-forestation, the development of carbon markets and the

construction of renewable energy sources. All of these activities

require the intimate involvement of the surveyor.

3. RESPONSIBLE GOVERNANCE – THE ROLE OF THE SURVEYOR

In 2012 the United Nations Environment Programme

issued its report on the most important emerging issues related to the

global environment (UNEP, 2012). The top ranked issue in that report

relates to aligning governance procedures to the challenges of global

sustainability. It involves the task of putting in place environmental

administrative and governance processes that are representative,

accountable, effective and transparent. This, too, is an underlying

theme in FIG (2010).

3.1 Measurement and Mapping

The land and seas form two crucial components of the

global environment. In the modern world, the first step to sustainable

governance of a resource is to understand the environmental

characteristics of that resource and its spatial dimensions. In this

regard, it is the surveyor who undertakes the spatial measurements that

determine the dimensions and the topography of both the land and the sea

floor. It is the surveyor who integrates these data into the Geographic

(or Hydrographic) Information System (GIS) that, in turn, allows these

areas to be displayed in digital form, thus providing the basic stepping

stone for their sustainable management and governance.

3.2 Administration and Governance

While the accurate definition of the global

topography is a vital component in any move towards global

sustainability, it is but a supporting part of a bigger picture. The

Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land,

Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (FAO,

2012), point to this bigger picture when they note the three important

elements of responsible governance. Such governance:

- Recognises and respects legitimate tenure right holders and

their rights.

- Safeguards all holders of these rights against threats and

infringements.

- Promotes and facilitates the use and enjoyment of these rights.

Amongst other things, states are encouraged to

establish up-to-date tenure information on land, fisheries and forests

and to hold this information in such a manner that ownership rights are

transparent. Where appropriate, land consolidation is suggested as a

means of improving layout and use. The Voluntary Guidelines then proceed

to recommend that,

“States should provide systems (such as registration,

cadastre and licensing systems) to record individual and collective

tenure rights in order to improve security of tenure rights“- (Sec.

17.1).

At their very essence, these tasks fall squarely

within the professional domain of the surveyor. In most jurisdictions it

is the surveyor who defines land (and sea) boundaries, who understands

the rights associated with the associated land parcels and who helps

devise the administrative and governance processes used to control these

parcels. The successful land titling project in Thailand that was

initiated in 1984 has served as a model for other Asian nations as an

example of what the surveying community can achieve (Brits et al, 2002).

On a much smaller scale it was two New Zealand surveyors who, in 1957,

travelled to Tonga to begin work on designing and implementing the

official cadastral survey system – a system that continues to work well

to this day. Their task was to help fulfill the constitutional

requirement that every Tongan man should be allocated an area of arable

land for the support of his family, (Alexander and Wordsworth, 2013).

Unfortunately, in some cases, while the surveyor may wish to be a change

agent, that which can be achieved is constrained by institutional

impediments such as political systems and gender bias. Long-term

sustainable solutions depend, in part, upon addressing such issues.

3.3 Land Use Planning

The 11th ranked issue in UNEP, (2012) is the need to

boost urban sustainability and resilience. The key to such

sustainability is seen to lie in the concept of “green” cities or “eco”

cities which differ from conventional cities in that they, “have a vital

mix of land uses within their borders, produce renewable energy and

provide low-energy transportation opportunities”. It is clear that the

design of such cities will require multi-skilled teams of whom the urban

planner is but one. It is of relevance to note that in some

jurisdictions (e.g., New Zealand and NSW, Australia) such planning

functions form an important part of the surveyor’s training and tool

kit. In these jurisdictions, the design of urban and rural subdivisions,

with their associated planning constraints, are an integral part of

professional surveying practice.

4. SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES (SIDS) – WHAT ARE THE ISSUES?

SIDS were first recognized as a distinct grouping of

countries at the UN Conference on Environment and Development held in

June, 1992. They are a distinct grouping of developing countries,

typically low lying, that share similar social, economic and

environmental vulnerabilities. Their greatest challenge is one of

sustainable development at a time when, for some, their very existence

may be under threat.

Briguglio (1995), in developing a vulnerability index

for such countries, noted their small size (thus leading to limitations

in natural resources, small domestic markets, a dependence upon exports

from a narrow range of products, and poor economies of scale), their

insularity and remoteness (resulting in high transportation costs and

uncertainties in supply), their proneness to a disproportionally high

level of disruption from natural disasters, and other environmental

factors. These other environmental factors were seen to include any or

all of the following:

-

depletion of natural resources leading to their

long-term unsustainability,

-

dependence upon external finance and skills and,

-

a reliance upon the use of the coastal zone for

tourism or marine related activities.

In many regards it is a combination of small size and

this latter reliance that makes them particularly vulnerable to sea

level rise and storm related devastation – both potential consequences

of climate change. It is thus no surprise that, amongst other things,

the 2005 Mauritius Strategy for SIDS (UN, 2005) specifically mentions

the need for strategies and actions related to climate change and sea

level rise, natural and environmental disasters, and land resources.

In order to provide a first measure of vulnerability,

Brigugilo (1995) developed a normalized vulnerability index. By his

assessment, SIDS countries had a vulnerability factor of 0.635 versus an

index of 0.418 for non-island developing countries and an index of 0.328

for developed countries. Even allowing for subsequent refinements in

these indices, the message remains clear, that SIDS are far more

vulnerable to natural disasters and external shocks than larger,

non-island developed nations.

Of the 52 identified SIDS countries, 14 are in the

Pacific Region. Of these 14, three (Tuvalu, Marshall Islands, and

Micronesia), are particularly subject to the consequences of sea level

rise. Indeed, even the seemingly modest rise of 18–59 cm by 2100, based

upon IPCC (2007) has the potential for very significant consequences.

Wong (2010) identifies some of the difficulties that the majority of

SIDS face with respect to climate change. Such difficulties include:

- Limited physical space within which to adapt.

- Small populations but with a high density, again limiting

adaptation options.

- Vulnerability to storm events of increasing severity.

- Relatively small watersheds and threatened water supplies.

- Narrow (and decreasing) range of land use makes

self-sustainability increasingly problematic.

- Increasing coastal hazard risk compromises tourism (typically an

important income earner).

In total, the problems arising from climate change

that directly affect SIDS are vastly greater in overall magnitude than

those facing many of the non-island developing nations. It is in this

arena that surveyors give thought to the contribution that they can

make.

5. PULLING IT TOGETHER - WHERE CAN SURVEYORS ASSIST?

The previous paragraphs provide a foundation for

understanding the role of surveyors and the particular problems faced by

SIDS. From them it should be clear that surveyors have an important role

to play in helping SIDS, not only in their development (as has been the

case in the past), but also in their adaptation to future change and the

mitigation of the effects of such change. The following avenues for

action are suggested.

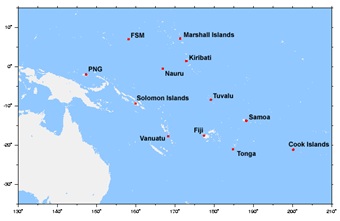

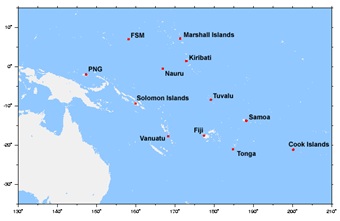

1. The provision, support and maintenance of

local, stable coordinate systems that not only support local mapping

but that will also allow change to be monitored. The South Pacific

Sea Level and Climate Monitoring Project, sponsored by the

Australian Agency for International Development, is a good example

of what can be achieved. The stations that are part of this network

are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Stations that are part of the S. Pacific Sea Level and Climate

Monitoring Project

While some additional work needs to be undertaken

to ensure the long-term stability of the local coordinate systems

used, work is now underway on the essential task of linking each of

these sites into a global reference framework. These links need to

be maintained into the future, driven in part, by the fact that many

of these stations lie in tectonically active areas. The

determination of any tectonic uplift or subsidence is an essential

element in understanding long-term sea level rise risk. Recent

studies in New Zealand, for example, have shown that the Wellington

region is subsiding at approximately 1.7 mm/yr, thus essentially

doubling the relative rate of sea level rise for that region from

2.0 mm/yr to 3.7 mm/yr (Bell and Hannah, 2012).

2. The integration of local land and resource

related data into a Land or Geographic Information System, thus

facilitating risk, disaster management and economic analysis. The

cadastre will form a fundamental layer in any such system. Given

that SIDS by definition are small, such systems need not be

expensive. Low cost GIS packages exist, as does open source

software. Unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) can now be used for

aerial data collection, both for remote sensing imagery and mapping

imagery. Although typically used for tasks that require fast data

collection and frequent observation of a specific area, the extent

of their coverage is a simple function of flying height and lens

focal length. UASs offer excellent potential to SIDS where the cost

of mobilizing traditional aerial mapping platforms is very high.

3. The rethinking of some traditional land-tenure

practices. In the South Pacific, some 83-97% of land remains vested

in the stewardship of indigenous guardians who retain the superior

interest in and control of the land (FIG, 2010). Where freehold

title to land has been granted in the past, or where such superior

interests exist, it may be time to move to more of a leasehold

model. Freehold implies permanency, whereas leasehold implies the

opposite. Preparing for future inundation, particularly in the

coastal margins, may be better served if land-holders had a more

temporary (or time-limited) view of their holdings or land tenure

rights. Equally, the compression of more people into increasing

limited land areas suggests that traditional land tenure rights over

the “safer” areas (most likely the higher standing land), will need

to be reconsidered.

4. Where appropriate, improved transparent

systems of land governance (e.g., registration, cadastre and

licensing systems) need to be implemented to record individual and

collective tenure rights. Such transparency will not only help

eliminate corruption, should it exist, but as noted in Point 2.

above, such systems form an essential and necessary pre-requisite to

effective land administration and management.

5. Improved land planning practices. It is clear

that land in the coastal margins will require either measures to

mitigate future sea level rise or will need to be subject to a

process of managed retreat. In either event, integrated coastal zone

management will be required. Such planning practices are becoming

established in some parts of New Zealand (Bell and Hannah, 2012).

“What if” scenarios are easily modeled by GIS software. In addition,

however, remaining arable lands will need to become more productive

if island communities are to at least maintain the status quo. While

precision agriculture finds its best use over large expanses of

arable land, there will be opportunities for its use in some island

communities.

6. New (or extended) research initiatives. The

susceptibility of Pacific SIDS to seismic activity and to vertical

tectonic motion is well known. However, the spatial extent of such

motion needs to be determined. This will require long-term GPS

monitoring campaigns such as is found in New Zealand’s GEONET (see

www.geonet.org.nz). In addition, work is required on assessing

alternative land tenure options and planning practices. It would be

preferable that that such activities be undertaken by local SIDS

communities wherever possible, but this, in turn, presupposes the

availability of a pool of skilled professional people. In some cases

this will require an investment in people.

CONCLUSIONS

Surveyors have traditionally played an unheralded but

leading role in the development of small nations. Their spatial

measurement, planning, and land administration skills have combined to

support the development of essential elements of island infrastructure.

As SIDS face the significant changes that lie ahead, the surveying

profession has the skill base to provide assistance through this next

phase of their development. In recent years it has perhaps been the

profession’s lack of public profile that has limited the call for such

contributions. This need not be the case in the future. The author would

advocate strongly that great benefit could be derived by SIDS if they

had greater access to the knowledge and skills that are an integral part

of the surveyor’s professional tool-kit. This should be an integral part

of their capacity building exercises.

REFERENCES

Alexander, B., and Wordsworth, L.S (2013). 100 Fathoms Square - the

Surveying of Tonga. Available from Bruce Alexander, 111 Hackthorne Road,

Cashmere, Christchurch, 8022, NewZealand.

Bell, R.G., and Hannah, J., (2012). Sea-Level Variability and Trends:

Wellington Region. Report prepared by the National Institute of Water

and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

Briguglio, L (1995). Small Island Developing States and Their

Economic Vulnerabilities”. World Development, Vol. 23, No. 9,

pp.1615-1632.

Brits, A-M., Grant, C., Burns, T., (2002). Comparative Study of Land

Administration Systems with Special Reference to Thailand, Indonesia and

Karnataka (India). Regional Workshops on Land Policy Issues, Asia

Program. Available at

http://www.landcoalition.org/sites/default/files/legacy/legacypdf/wbtcsind.pdf?q=pdf/wbtcsind.pdf

Church, J.A., and White, N.J., (2011). Sea-Level Rise From the Late

19th to the Early 21st Century”. Surveys in Geophysics 32:585-602,

doi:10.1007/s10712-011-9119-1

FAO, (2012). Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of

Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food

Security, available from FAO, Rome.

FIG, (2004). Found at

www.fig.net/general/definition.htm and accessed

on 4 Sept. 2013.

FIG, (2010). Sydney Agenda for Action (Small Island Developing States

and the Millenium Development Goals: Building Capacity). FIG Publication

No. 53, available from

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub53/figpub53.pdf

Hannah, J., Bell, R., Paulik, R., (2010). Sea-Level Change in the

Auckland Region. Report prepared for the Auckland Regional Council.

Hannah, J., and Maseyk, J., (1989). The Definition and Adjustment of

the Fiji Geodetic

Datum – 1986. Survey Review, Vol. 30, No. 1.

IPCC, (2007). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and

Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

Mardkheh, A.J., Mostafavi, M.A., Bédard, Y., and Long, B., (2012).

Toward a Spatial Decision Support System to Improve Coastal Erosion Risk

Assessment: Modeling and Representation of Risk Zones. Presented at the

FIG Working Week, Rome, May, 2012. Available at

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2012/papers/ts04k/TS04K_jadidimardkheh_mostafavi_et_al_5958.pdf

UN, (2005). Found at http://www.sidsnet.org.

UNEP, (2012). 21 Issues for the 21st Century: Result of the UNEP

Foresight Process on Emerging Environmental Issues. United Nations

Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

White, N., (2013). Historical Sea-Level Changes Over the Last Two

Decades. CSIRO sea-level rise web site:

http://www.cmar.csiro.au/sealevel/sl_hist_last_15.html

Wong, P.P. (2010). Small Island Developing States. WIREs Climate

Change 2011 2 1-6 DOI:10.1002/wcc.84. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

John Hannah completed his BSc (Surveying) in 1970, a Post Graduate

Diploma of Science in 1971, and became a Registered Surveyor in New

Zealand in 1974. He subsequently completed an MSc and PhD at The Ohio

State University. From 1982 -1988 he was employed by the Dept. of Lands

& Survey, New Zealand as a Geodetic Scientist and then as Chief

Geodesist/Chief Research Officer. After an appointment to the Chair in

Mapping, Charting and Geodesy at the US Naval Postgraduate School,

California in 1989-1990, he returned to New Zealand as Director of

Geodesy and then Director of Photogrammetry for the Dept. of Survey and

Land Information. In 1993 he joined the School of Surveying at the

University of Otago as Professor and Head of Department. He became the

School’s Dean in 2001, relinquishing this role at the end of 2004. From

2005-2007 he was President of the NZ Institute of Surveyors. He retired

from the University of Otago in 2012 and is currently the Managing

Director of his own consultancy, Vision NZ Ltd. He is Chair of the FIG

Task Force on Climate Change and is on the Council of Standards New

Zealand.

CONTACTS

Emeritus Professor John Hannah

University of Otago Vision NZ Ltd.

School of Surveying

22 Woodstock Place

PO Box 56 Stoke

Dunedin 6054 Nelson 7011

NEW ZEALAND

Tel. + 64 3 479 7585; + 64 3 547 3061

Fax + 64 3 479 7586

Email: john.hannah@otago.ac.nz

and jandlhannah@gmail.com

Web site: www.otago.ac.nz

|