Article of the Month -

March 2006

|

Cadastre in Itself Won’t Solve the Problem: The Role of

Institutional Change and Psychological Motivations in Land Conflicts – Cases

from Africa

Dr. Babette WEHRMAN, Germany

This article in .pdf-format

This article in .pdf-format

1)

This article has been prepared for the 5th FIG Regional Conference -

Promoting Land Administration and Good Governance to be held in Accra,

Ghana, March 8-11, 2006. This paper was not presented in the conference.

Key words: land conflicts, land market, land administration,

institutions, psychological motivation, conflict resolution

1. INTRODUCTION

The governments of many African countries are currently investing in the

improvement of their land administration – aiming mainly to develop an

efficient land market. As a side product, there is the objective to decrease

land conflicts through the implementation of a functioning land registration

and/or cadastral system. Experience, however, shows that more is needed than

surveying, demarcation and land registration to avoid severe land conflicts.

The question therefore arises what are the deeper roots of land conflicts

and how can we respond to them.

2. SHORT-COMINGS OF THE LAND MARKET AND ITS INSTITUTIONS FACILITATING

LAND CONFLICTS

2.1 Economic efficient land markets can cause land conflicts

Not only imperfect land markets, even a perfect land market cannot

prevent land conflicts if it is not regulated by institutions. For the

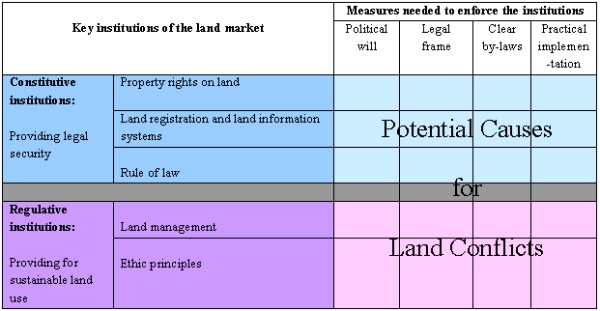

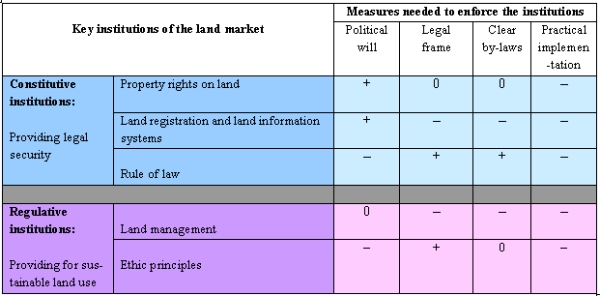

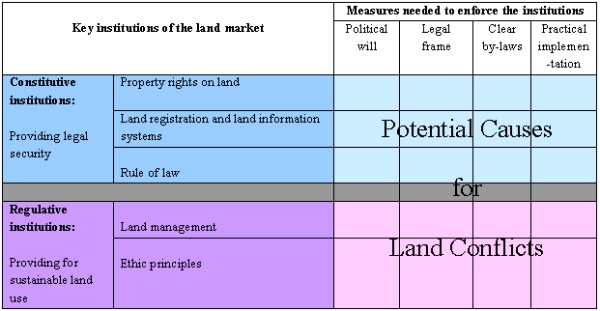

purpose of this paper two types of institutions are distinguished:

constitutive and regulative institutions. Constitutive institutions are

needed to enable an economic efficient land market to work (such as land

rights, land registration and rule of law), while regulative institutions

are necessary to make the land market socially sustainable and

environmentally sound (such as land management and ethic principles).

However, even if all these institutions are in place, land conflicts can

still occur. This is mainly due to extreme emotional and material needs.

2.2 Institutions constituting and regulating the land market to

minimize land conflicts do not work properly in developing countries

In most African countries, many constitutive and regulative institutions

have massive functional deficits: Land rights are most often characterized

by a fragmented or overlapping legislation and legal pluralism, resulting in

unclear property rights and consequently land ownership conflicts. Land

administration authorities dealing with land registration, land information

systems, land use planning and land development lack trained staff,

technical infrastructure, and financial resources. Beyond that,

administrative services are over-centralised and responsibilities are often

not clearly assigned or overlap each other, thus impeding cooperation and

coordination. As a result, the little available and mostly incomplete or

isolated data on land ownership and land use is being gathered by different

non-cooperating institutions, making it difficult or even impossible to use

it properly. Endless procedures and low levels of implementation are the

result. Therefore, neither institutions constituting nor those regulating

the land market make a substantial contribution to avoiding land conflicts.

Given the low salaries and the openness to motivation payments of the people

working within these institutions they rather contribute to land conflicts.

Legal security is furthermore limited by insufficient implementation of

rule-of-law principles, while mechanisms for sustainable land development

suffer from the fact that ethical principles are not broadly acknowledged.

For all institutions, lacking implementation is the crucial point. Unclear

implementation guidelines and contradicting legislation worsen the

situation. Political will is very unsteady. Generally, it can be concluded

that imperfect constitutive institutions of land markets promote land

ownership conflicts, while poor regulative institutions are responsible for

land ownership as well as land use conflicts.

Fig. 1: Constitutive and regulative institutions

of the land market

Own draft

3. THE DEEPER CAUSES OF LAND CONFLICTS

3.1 Dysfunctional institutions only act as catalyst of land conflicts,

selfish individual interests being the deeper causes

It needs to be stressed that functional deficits are not the core reason

for land conflicts; they merely facilitate them. Profit maximisation of a

multitude of actors is the driving force, either by unjustly grabbing land

or by excluding disadvantaged sections of the population from legally using

land. Theoretically, these actors include all social gate keepers, mostly

identical with principals in principal-agent-relationships. Notoriously low

wages in the public sector contribute to corrupt behaviour of social

gatekeepers in this field. In my opinion, however, the decisive factor for

these irregularities is the “normality of misbehaviour”: Nepotism,

corruption, and disregard for regulations are considered normal by the

population. Social and religious values are of little relevance for everyday

life; self interest is paramount to public interest. This underlines the

importance of ethical values and rule-of-law principles in preventing land

conflicts. If individual profit maximisation – under widespread absence of

functioning institutions – is the underlying reason for land ownership

conflicts, then a capitalistic land market associated with increasing land

prices can be seen as facilitator. (For as long as land has no monetary

value, land ownership conflicts occur comparably seldom.) In this situation,

dysfunctional institutions constituting and regulating the land market act

merely as catalysts of land conflicts – especially in times of institutional

change.

3.2 Psychical fears and desires resulting in emotional and material

needs are at the root of land conflicts

As any egoistic behaviour, taking advantage of functional deficits for

the sake of reckless individual profit maximisation is based on emotional

and material needs, which again are a consequence of psychical fears and

desires. Therefore, psychical phenomena form the basis of land conflicts. A

typical psychical fear is the fear of existence. This fear can result in

extreme emotional and material needs such as the need for shelter, the

longing for survival and self-esteem – in some cases resulting in a desire

for power – and strong need for independence – often resulting in the

accumulation of wealth. It is mainly the combination of very strong

emotional and material needs (seeking power and wealth) that let people

either break rules (institutions) or profit from institutional shortcomings.

Land conflict resolution should therefore look at the psychical fears and

desires of those breaking the law or profiting from loopholes – especially

in those situations where illegal behaviour is rather the rule than the

exception. This is the case in many post-conflict countries where psychical

fears and desires and the thereby provoked emotional and material needs are

a common phenomena influencing the entire society and overall development.

4. INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE AS CATALYST

Institutional changes are conflict prone and therefore tend to be phases

of increased land conflicts. While some forms of land conflicts can occur

under different and even stabile institutional frame conditions (such as

border or inheritance conflicts), others depend on the kind of institutional

change. Multiple sales due to legal pluralism for instance are typical for

slow institutional changes that lead to the overlapping of two systems,

while illegal sales of state land are quite common in situations of either

abrupt institutional change that are marked by a temporary absence of rules

(transformation) or longer term absence of a functioning legitimated

institutional frame (civil war, dictatorship).

5. INTERDEPENDENCY OF FACTORS CAUSING LAND CONFLICTS

Changing frame conditions often provide the base for land conflicts:

natural disasters such as droughts and floods leading to rural-urban

migration, natural population growth, the resulting increase in the demand

of land and consequently land prices, the introduction of the market economy

giving land a monetary value and thereby eradicating traditional ways of

land allocation, increasing poverty making it difficult to acquire land

legally and last but not least an institutional change causing a temporary

institutional vacuum at the land market create fears, desires, needs,

interests, attitudes and opportunities concerning land use and ownership

that are no longer controlled and therefore easily lead to land conflicts

(see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Interdependency of land conflict causes

Own draft

Poverty, institutional change and other changes in society (including war

and peace) influencing each other provoke strong psychological desires and

fears (such as fear of existence, desire to be loved) which result in

extreme emotional and material needs (such as the need for shelter, feelings

of revenge, the longing for survival and self-esteem – in some cases

resulting in a need for power – and strong need for independence – often

resulting in the accumulation of wealth). Given the institutional

shortcomings due to institutional change, these emotional and material needs

– sometimes supported by the sudden opportunities to reap economic profits –

result in either taking advantage of institutional weaknesses, ignoring

formal and/or informal institutions or in preventing their

(re-)establishment.

Looked at these causes from a different analytical perspective, they can

also be distinguished in political, economic, socio-economic,

socio-cultural, demographic, legal, administrative, technical (concerning

land management), ecological and psychical causes (see Fig. 3). All of these

causes are also included in the model presented in figure 2: Political,

economic, socio-economic, socio-cultural, demographic and ecological causes

are part of the changing framework. Legal, administrative and technical

causes are summarized under the institutional shortcomings. The psychical

causes have already been addressed (see 3.2).

Fig. 3: Causes of urban and peri-urban land

conflicts

|

Causes |

Examples |

| Political causes |

- change of the political and economic system

- lack of political stability and continuity, lack of predictability

- introduction of (foreign, external) institutions that are not

accepted

- war/post-war situation

|

| Economic causes |

- evolution of land markets

- increasing land prices

- limited capital market

|

| Socio-economic

causes |

- poverty and poverty-related marginality/exclusion

- extreme unequal distribution of power and resources (incl. land)

- lacking micro-finance options for the poor

|

| Socio-cultural

causes |

- destroyed or deteriorated traditional values and structures

- rejection of formal institutions (new, foreign, external)

- low level of education and lack of information on institutions and

mechanisms of land markets

- high potential for violence

- abuse of power

- strong mistrust

- helplessness of those disadvantaged

- unregistered land transactions

- fraud of administration and/or individuals

- patronage-system, clientelism

- strong hierarchical structure of society

- heterogeneous society, weak sense of community, lacking

identification with society as a whole

|

| Demographic

causes |

- strong population growth and rural exodus

- new and returning refugees

|

| Legal causes |

- legislative loopholes

- contradicting legislation

- legal pluralism

- traditional land law without written records or clearly defined

plot and village boundaries

- formal law which is not sufficiently disseminated and known

- limited claims of legal entitlement by disadvantaged

- insufficient establishment of rule-of-law-principles (e.g. lack of

independent courts)

- insufficient implementation of legislation

- missing or not applied mechanisms for sanctions

|

| Administrative

causes |

- insufficient implementation of formal regulations

- centralism (e.g. centralised land use planning)

- corruption

- insufficient control over state land

- lack of communication, cooperation, and coordination within and

between different government agencies as well as between public and

private sector (if existent at all)

- lack of responsibility/accountability

- limited access (distance, illiteracy, costs etc.)

- insufficient information for the public

- limited/inexistent public participation, especially in land use

planning

- insufficient staff and technical/financial equipment of public

agencies

- very low wages in the public sector

- low qualification level of public employees

- missing code of conduct

- lack of transparency

|

Technical

causes |

- missing or inaccurate surveying

- missing land register (e.g. destroyed) or it does not meet modern

requirements

- missing, outdated or only sporadic land use planning or not

adapted to local conditions

- insufficient provision of construction land

- missing housing programs

|

| Ecological causes |

- erosion/drought/floods leading to urban migration

- floods and storms in squatter settlements

|

| Psychical causes |

- fear for one’s existence

- lack of self-esteem

- loss of identity

- collective suffering

- desire for revenge

- thirst for power

|

Source: Wehrmann 2005

6. EXAMPLES FROM DIFFERENT AFRICAN COUNTRIES

6.1 Accra, Ghana

The institutional change that occurred in Ghana which still has an impact

on the current situation started with the colonalization. The import of

colonial/European/British institutions that have been introduced by the

British and later be kept after independence by the now independent Republic

of Ghana resulted in legal pluralism that still characterizes today’s

situation. The slow transformation from one system to another has never

destroyed the entire institutional framework – although many formal as well

as informal institutions are ignored. While being weak, the institutional

setting functions to a certain degree.

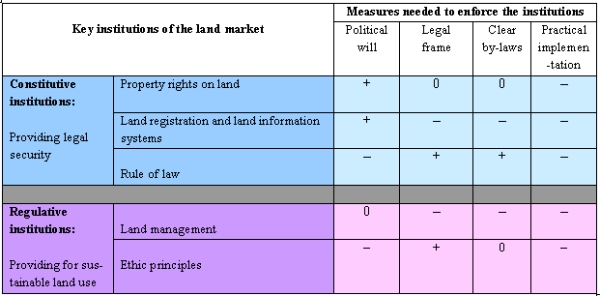

Fig. 4: Constitutive and regulative institutions

of the land market in Accra

Wehrmann 2005

An analysis of the land market insitutions in Accra showed that the

weakest point is the implementation. The questions now is why are the formal

institutions not implemented sufficiently. Apart from limited financial

means and human capacities, lack of coordination and cooperation etc. a main

problem is the lack of acceptance of formal institutions. This might partly

be due to long procedures and high (official as well as inofficial) costs

but it also reflects people’s general perception of and attitude towards the

state. What’s the reason for it? The negligence of autochthonous

institutions and the attempt to replace them by external models (European

institutions) have in certain cases resulted in non-acceptance and

viola¬tions of government regulations by traditional authorities. Multiple

sales of land by different traditional chiefs (head of stools, head of

families) and the violation of land use regulations by individuals represent

the most common forms of land conflicts.

In spite of all the existing laws and the many institutions dealing with

land management and land administration, there have been more than 60.000

land cases in Accra at the beginning of the new millenium, keeping the

courts busy (Daily Graphic, 15.11.2001). The most common land conflicts

apart form boundary conflicts are multiple sales of land. These are

conflicts where several people – most often traditional authorities – claim

being the owner and sell the land to different innocent clients. Although

these activities are facilitated by the weaknesses of the land

administration, the question remains why some people exploit them while

others don’t.

The egoistic exploitation of institutional weaknesses is partly due to

the people’s hurt feelings that are a result of the collective negative

experience of taking away traditional institutions which are part of the

traditional culture and thereby identity of the people. The exploitation of

institutional weaknesses and the misuse of institutions is further motivated

by the human pursuit of wealth and by the emotional longing for status so

typical of African societies and particularly common among traditional

chiefs (Wehrmann 2005)

6.2 Johannesburg, South Africa

The most previous institutional change in South Africa was the transition

from apartheid to the post-apartheid system. The change in law, giving –

among others – freedom of movement to everybody resulted in massive

migrations of Black people from homelands and townships towards the (big)

cities in search of work. In Johannesburg, many of these people looking for

housing became “victims” of the land mafia – or with other words had been

provided with land by the land mafia. The new-comers often stayed in shacks

they built in the backyard of friends or relatives living in a township

close to the city. Many of them became organized by local, informal

community leaders and often got into contact with the land mafia. A team of

land mafioso identified a group of landless, already organized people and

charge them R 50 (about US$ 10) each to sign up on a list. Once they had

brought together about 2000 signatures (which corresponds to R 100.000 / US$

20.000), they choosed a suitable site to occupy. This was planned very

precisely and often carried out with professional assistance. They completed

deeds searches on the land to determine who owns it and used skilled

planners to structure a settlement on paper. They avoided occupying private

land because they know that the government will treat them softer than

private owners. Once the squatters are settled, they had to pay a monthly R

50 (US$ 10) rent and an additional R 20 (US$ 4) „protection fee“ to the land

mafia. They also paid another R 10 (US$ 2,50) legal fee every month. The

legal fee was paid into a fund so that a legal representative could have

been called in if action would have been taken against the squatters (Reeves

1998; Wehrmann 1998).

Actors in this land conflict are the poor searching for land and the

people acting as land mafia. While the poor’s motivation is mainly the need

for shelter (material need), the land mafia is motivated by the search for

wealth (material and emotional need). The people acting as land mafia are

mainly state officials or well educated, highly qualified people who work

within the administration dealing with land issues or who have close

relations to state officials. They get the information from within the

system and exploit it for their private benefit – thereby exploiting the

state and taking advantage of institutional shortcomings – mainly concerning

the control of land development and the use of sanctions.

The example of the land mafia shows that land conflicts do also occur

even when a land registration/deeds cadastre is in place and when there are

just little or no institutional shortcomings. This underlines the importance

of psychic motivation, material and emotional needs as deeper causes of land

conflicts and highlights the need to address them if land conflicts shall be

limited.

6.3 Kenya

Misuse of power, motivated by psychic desires and the resulting emotional

and financial needs, are also the mayor cause of the big land conflicts in

Kenya which consist in land grabbing and illegal land allocations by

influential people. The Ndung’u report from 2004 revealed that the former

presidents Kenyatta and Moi as well as cabinet ministers, former high

ranking civil servants and other influential people illegally acquired title

deeds. They grabbed land from farmers as well as forest areas, game parks

and reserves – mainly with the support of public officials. The report asked

for the prosecution of those people who illegally gained land and those

public officials being involved in land grabbing. The report also demanded

to set up a Land Titles Tribunal to clarify ownership. As a final objective

all illegally acquired title deeds should be cancelled.

Fig. 5: Kenyatta and Moi accused of illegal land

allocation

Source: Daily Nation, 7.10.2004

This third example shows once more that the individual motivation of

people and their chances to manipulate the system are crucial factors in

land conflicts. The motivation can, however, be very different: a poor

landless person’s psychic desires and material needs resulting in the

illegal occupation of a small spot is definitely different from a

president’s psychic desires when he sells out state land or registers huge

areas on his own name. The crucial issue is to identify the emotional and

material needs and the psychic desires behind to find alternative solutions.

A person’s desire for power, influence and maybe even wealth might be

satisfied in a different way (e.g. by attributing additional status through

other means) which allows transferring at least part of the state and

private property back to the original owners.

7. CLASSIFICATION OF LAND CONFLICTS

Among the many different ways to classify land conflicts (Wehrmann 2005)

the one based on the social dimension of conflicts is the most suitable of

all – especially when it comes to conflict resolution. One possibility of

classification conflict research offers in this regard is the distinction

according to the social level where a conflict takes place: inner-personal,

interpersonal, inner-societal and inter-societal/international level. While

in the case of land conflicts the inner-personal level can be ignored, the

other three levels are very useful for a classification. Land conflicts

within one country will then occur at either the interpersonal or

inner-societal level (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 6: Classification of land conflicts according

to social level and dimension

Own draft

Another, however quite similar way of conflict classification is based on

the social dimension of the conflict, distinguishing between micro-societal,

meso-societal and macro-societal dimension. While the micro-societal

dimension is equivalent to the interpersonal level, the other two allow a

more precise classification of inner-societal conflicts (see Fig. 4).

The classification of land conflicts according to their social dimension

illustrates the high number and diversity of inner-societal land conflicts

compared to inter-personal land conflicts (which, however, does not tell

anything about their absolute number). While in most cases interpersonal

land conflicts can be addressed by existing formal or informal conflict

resolution bodies (see Wehrmann 2005), inner-societal conflicts are much

more difficult to tackle – mainly because conflict resolution mechanisms at

the higher level are part of the problem.

8. LAND CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND PREVENTION

In the long term, land conflicts can only be resolved and avoided if

addressed with an integral and system-oriented approach. Core elements of

conflict resolution and prevention are therefore the establishment of a

state under the rule of law and the implementation of good governance to

minimise the abuse of power and corruption. Beyond that, an active trauma

counselling and a reappraisal of historic injustice by integrating

psychotherapeutic methods are required to restore missing trust in the state

and its institutions. Further elements of conflict resolution are

functioning regulative and constitutive institutions of land markets, which

have been locally adapted, a transparent capital market and a coordinated

system of arbitration boards and jurisdiction. Good governance is of

particular importance in this context. Its criteria such as sustainability,

subsidiarity, equality, efficiency, transparency, accountability, public

participation and security – if applied to land tenure and urban land

management – form a good basis for development of cities in developing

countries to be relatively free of land conflicts (see WEHRMANN ET AL. 2002;

MAGEL/WEHRMANN 2001).

Tools and approaches to avoid and resettle land conflicts can be

distinguished in preventive and curative measures. The preventive measures

mainly focus on the institutional frame conditions such as:

- the establishment and strengthening of the constitutive institutions

(rule-of-law, secured land tenure and land registration/cadastre),

- the establishment and strengthening of the regulative institutions

(spatial planning, guided land use changes, land market monitoring, land

banking, proportional tax benefits for the state as land value increases

(mainly in peri-urban areas) and promotion of ethnic principles) and

- the establishment and control of an accessible and transparent capital

market.

The curative measures include a much broader range of activities.

Among them three types of measures can be distinguished:

- Conflict resolution, including moderation, mediation and arbitration.

Conflict resolution can take place at different levels; it can be applied

within the formal as well as within the informal sector or even in mixed

forms, so called hybrid structures. Conflict resettlement institutions can

also be based within the administration – be it the state or the

traditional administration.

- Land management, including different ways to clarify land rights and

secure tenure, surveying and land registration, land consolidation, land

readjustment, land sharing, land pooling, land use planning, investments

into the housing market (including housing for the middle class, social

housing, social concessions, site and service programs and site without

service programs), recovery of state assets and an increase of

transparency and documentation of land conflicts (e.g. through state land

inventories, special GIS which document land conflicts).

- Psychotherapeutical approaches. Land conflicts as any other type of

conflict often end up in vicious circles when the conflict parties stick

to their positions and unconsciously force each other to represent

increasingly extreme positions. People normally tend to project negative

characteristics on each other until the opposite party finally

incorporates them. Reality becomes more and more disguised and the other

conflict party ends up being responsible for all negative aspects in life,

e.g. squatters often make the state responsible for all their problems

while the state considers them as a handicap to any development. In such

situations it becomes necessary that both conflicting parties change their

perception of the other to pave for an equitable dialog. This can be

achieved by a sociodrama (a kind of psycho-analytical/therapeutical role

play). As generally it cannot be expected that both parties will do it

together, they can at least do it among themselves, thereby experiencing

the feelings of the other party and developing empathy for their position,

behaviour, interests and needs. As an alternative, street theatre and TV

soap operas can be used to deal with typical land conflicts people are

typically involved in.

Land conflicts can only be minimized if all approaches are combined as

required by the specific land conflict and adopted to the specific

situation, respecting existing rules, organisational structures and the

overall cultural, political, legal, economic and social frame conditions.

9. CONCLUSION

Institutional changes are conflict prone and therefore tend to be phases

of increased land conflicts. While some forms of land conflicts can occur

under different and even stabile institutional frame conditions (such as

border or inheritance conflicts), others depend on the kind of institutional

change. Multiple sales due to legal pluralism for instance are typical for

slow institutional changes that lead to the overlapping of two systems,

while illegal sales of state land are quite common in situations of either

abrupt institutional change that are marked by a temporary absence of rules

(transformation) or longer term absence of a functioning legitimated

institutional frame (civil war, dictatorship). The dimension of (the

physical and psychological) violence that occurs, however, always depends

strongly on the conflict asymmetry, which despite of all the differences of

land conflicts leads to similar patterns of inter-personal relations – a

fact that underlines the importance of the inherent psychosocial dynamic.

The case studies illustrate that institutional change as well as other

elements of change and a low level of development can result in massive

deficits in the institutional framework of land markets. These functional

weaknesses can enable land conflicts. Land conflicts are however rather

caused by the egoistic exploitation and intentional continuation of

institutional gaps and by the disregard of formal institutions than by an

absence of rules or an overlap of regulations. Reasons for this are of

psychical nature: The fact that the state widely ignores legitimate informal

institutions triggers off an act of defiance by the population. In turn,

governmental institutions and their rules are likewise disregarded. This can

lead to massive violations of land use regulations and consequently to land

use conflicts. The material desire for wealth and the emotional desire for

status – especially pronounced in African societies – additionally

contribute to the violation of regulations. In civil-war and post-conflict

countries, the exploitation and continuation of institutional weaknesses is

particularly common, which again can be understood when considering the

psychological factor. Civil war evokes and intensifies extreme psychical

fears (fear of loss and of existence) and desires (revenge, power), which

create particularly pronounced material needs for ensuring one’s livelihood

and wealth as well as emotional needs for respect and thus (moments of)

power. This means that almost all sections and social strata of the

population are involved in land conflicts, which are more diverse, more

frequent and more often result in violence than in a situation of legal

pluralism. Thus, the primary reasons for land conflicts are peoples’

psychical desires and fears as well as their emotional and material needs.

The pursuit of resulting individual interests is considerably facilitated by

the lack of an institutional framework. As a general rule, it can be assumed

that a weakness of those institutions constituting the land market enables

the outbreak of land ownership conflicts, while insufficient regulative

institutions result in land ownership and land use conflicts alike.

The complexity of causes leading to land conflicts as well as their

diversity and the huge number of different actors involved requires an

integral, system-oriented approach. Besides functioning constitutive and

regulative institutions and their adaptation to local requirements, a

transparent capital market and a coordinated system of arbitration boards

and legislation, the core elements of conflict resolution and prevention are

the establishment of rule-of-law principles, the implementation of good

governance to reduce abuses of authority and corruption as well as the

integration of psycho-therapeutical methods to re-establish mutual trust and

respect among conflict parties. In this context, good governance is of

particular importance. To transfer its criteria (sustainability,

subsidiarity, equality, efficiency, transparency, accountability, public

participation and security) on land policy and land management would provide

a good basis for sustainable and low-conflict development in African

countries. The due establishment of this positive framework is of crucial

importance, especially in situations of crisis such as in

post-conflict-countries. An established, legitimated and widely accepted

framework is necessary to avoid abuse and thus further land conflicts before

technical approaches like land registration can be implemented. Only then,

the following is true: „No matter how difficult concerted action might seem

in the chaos and confusion following conflict, land questions have to be

dealt with as early as possible” (Du Plessis 2003, p. 8). It goes without

saying that each land conflict needs its individual solutions which are

adapted to its local, regional, national and supranational political,

socioeconomic, cultural and power-related frame conditions. It depends on

each specific case which of the tools and approaches presented can or must

be applied for effective solutions on land conflicts.

REFERENCES

- Du Plessis, J. (2003): Land plays a key role in post-conflict

reconstruction. In: Habitat Debate, Vol. 9/4, p. 8.

- Magel, H. and Wehrmann, B. (2001): Applying Good Governance to Urban

Land Management – Why and How? In: Zeitschrift für Vermessungswesen (ZfV)

Vol. 126, pp. 310 – 316.

- Reeves, J. (1998): The move form slums to suburbs. In: Saturday Star,

21.2.1998.

- Wehrmann, B. (2005): Landkonflikte im urbanen und peri-urbanen Raum

von Großstädten in Entwicklungsländern – mit Beispielen aus Accra und

Phnom Penh. Urban and Peri-urban Land Conflicts in Developing Countries.

Berlin 2005.

- Wehrmann, B. (1998): Urban Informal Land Markets with a special focus

on South Africa. In: International Workshop on Comparative Policy

Perspectives on Urban Land Market Reform in Latin America, Southern Africa

and Eastern Europe. Workshop-documentation. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA,

7 – 9.7.1998.

- Wehrmann, B. et al. (2002): Good Urban Land Management. In: Trialog

74, 3/2002, pp. 13 – 19.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

The author is geographer and social anthropologist with many years work

experience in development cooperation and academic education. She has been

working in Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America in the fields of urban and

rural development, governance and decentralisation as well as land

management and land policy. She did her PhD on land conflicts in developing

countries. From 1995 – 2000 she worked as junior expert for the German

Development Cooperation (GTZ). Since 2000 she is program manager at

Technische Universität München where she set up an international master’s

program on land management and land tenure. She is also conducting research

projects abroad and doing consultancy for different international

organisations. She has published more than a dozen articles on land and

development issues in developing countries.

CONTACTS

Dr. Babette Wehrmann

Technische Universität München, Centre of Land Management and Land Tenure

Arcisstr. 21

80290 Munich

GERMANY

Tel. + 49 – (0)89 - 28925789

Fax + 49 – (0)89 - 28923933

Email:

Wehrmann@landentwicklung-muenchen.de

Web site:

www.master-landmanagement.de

|