Article of the Month -

May 2009

|

Making Land Markets Work for All

Ms. Jude WALLACE

Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration

The University of Melbourne, Australia

This article in .pdf-format (15 pages

and 567 KB)

This article in .pdf-format (15 pages

and 567 KB)

1) This paper was prepared and

presented for the first time in session MKTl: Potential and Challenges

for Land Markets at the FIG and World Bank Conference on Land Governance

in Support of the MDGs: Responding to New Challenges, Washington DC,

USA, 9-10 March 2009.

Key words: land markets, property, administrative systems.

SUMMARY

The design of land administration systems needed to support land

markets now benefits from the broader theoretical framework of the

discipline. The arrival of new “tool box” approaches has also enriched

our capacity to design systems that work despite the diversity of

national approaches and experiences.

The central feature of land markets is the concept of property. The

concept is cerebral, conceptual and divorced from physical reality: this

is both its challenge and its weakness. The property concept appears at

an early stage in development of land markets but is not well

understood. Despite popular thinking, design of land administration

systems for land market operations does not revolve around managing

land. Rather the design revolves around management of this abstract and

cerebral concept, with management of land itself as an essential but

secondary function.

An analysis of the stages of development of systems of market

administration can help explain how markets develop abstract concepts

into commodities. The stages can help national implementation of

pro-market systems without sacrificing pro-poor initiatives. Sensible

administration should deliver a balanced concept of property that fits

both the way the local people think about their land and the capacity of

their government to manage systems.

1. THE COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF LAND

Designers of administration systems that support land markets work

must understand how these markets work and how administrative frameworks

might manage essential trading processes. This is not economics but the

practical world of managing both the obvious and the hidden processes

that people use to trade in land-based commodities. Though we can debate

the boundaries of these numbers, of the 200 or so national

jurisdictions, only about 35 offer transparent management of all the

basic processes involved in their land markets. The 35 are roughly

equivalent to OECD members and the liberal democracies of Western

capitalism. Even these 35 experience constant reifications of their

systems as they adjust to evasions, frauds, dysfunctions and

maladjustments that constantly occur. Witness the sub-prime mortgage

crisis in 2008 in the US, and its consequences through out the globe in

2009. For this lucky 35, and indeed for the rest of the world,

management of land market processes is getting more difficult.

All markets require commodities and trading systems. From a land

administration perspective, management of land market processes is

complicated and cannot be based solely on the assumption that land

markets are fundamentally about land as a commodity. In mature land

markets commodities are much more interesting than most analysts

realize. These land-related commodities have two aspects.

The popular aspect is the visible and tangible – the houses and land,

the farms, factories and raw development sites. In short, the physical

land. The analysis of the physical aspect of land markets is extensive.

These tangible “things” are popularly thought of as the commodities,

with land administration consequently concerned about their management.

Eventually, this popular approach will restrict the development of land

markets by impeding development of a property concept that allows land

markets to develop complex commodities.

The second aspect is abstract but no less a reality – it exists

however in peoples’ minds. In successful market systems the commodities

are abstract interests and rights. Their essential nature is not the

objects to which they relate but the way systems manage relationships

among people in relation to those objects (Cohen 1954). The

administrative systems define the cognitive identity of the interests so

they can be managed and traded. This cognitive aspect is in fact far

more important than the tangible aspects of land in any community in

that it delivers the capacity to use land to accelerate wealth. The

fundamental challenge for land market analysts and designers of land

administration systems is management of these transcendental aspects of

commodities. The primary commodity is the land right and its supporting

aspects of transferability, knowability, title and tenure which together

should deliver comprehensive and predictable access to opportunities to

derive wealth out of land-related interests and to manage these

opportunities according to sustainable development objectives. In market

based systems, access to and regulation of land is designed to

institutionalize a concept of property on a national scale (North 1990).

2. A LAND ADMINISTRATION APPROACH – ENGINEERING AND TOOL BOXES

Land administration is a new discipline which applies an engineering

approach to building systems that support land management and land

markets. The engineering approach has notable features. It relies on

tools to manage essential processes and functions, and tests their

performance to continually improve them. The disciplinary vision of land

administration is now extensive and focuses on land management as a

paradigm (Stig Enemark 2006). In this paradigm, the key processes are

those associated with four fundamental functions in land management:

land value, land tenure, land use and land development. Every settled

society undertakes these functions. Some use processes that develop

accidentally. Others rely on highly planned and sophisticated processes.

Successful land markets demand well run processes because they build

exceedingly complex concepts of property.

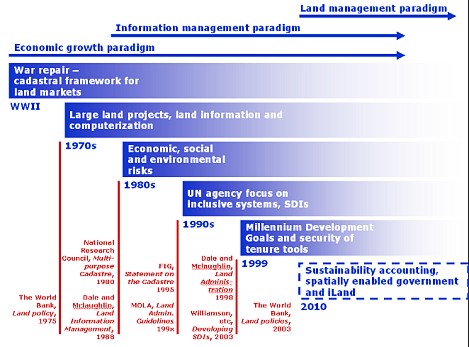

Land administration has changed dramatically since it emerged after

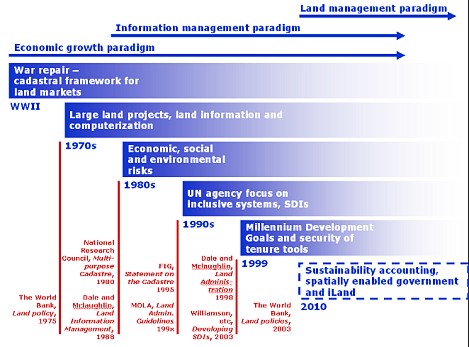

World War II from its more ancient historical antecedents. Figure 1

below shows the development trends in the discipline, particularly its

emergence from its technical constraints into a multi-faceted discipline

with adaptable boundaries and best practice models that emphasise

overall good governance, participation and sustainable development.

These models increasingly rely on remarkable new technologies, and

robust theories of property.

Figure 1. Development of the land administration discipline

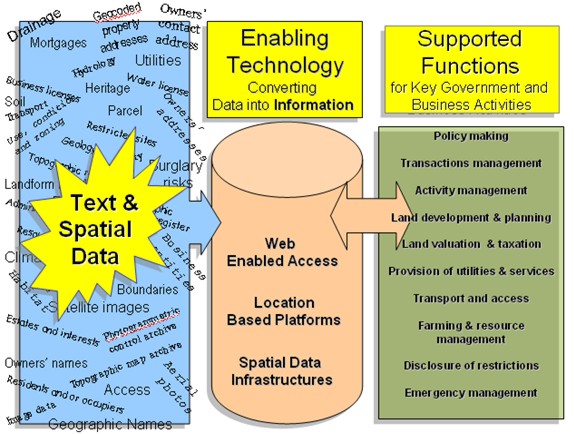

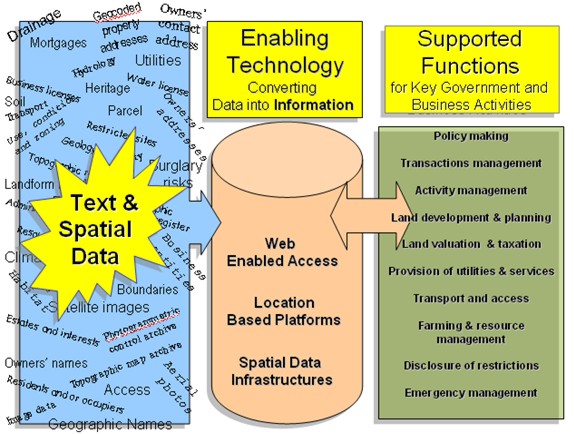

The technical focus of modern land administration remains important

in countries with successful land markets. Figure 2 below

illustrates how these countries generate complicated land arrangements

and concepts that they initially define as pure information. The

technical approach is required to manage information, then convert

information into data to support strategic activities for modern

governments, businesses and societies.

Figure 2. The modern information functions of land administration

systems

The engineering paradigm required a pragmatic approach to designing,

constructing and managing these information systems. But it in mid 1990s

it was apparent that a focus on land information was not enough.

Meanwhile technological capacity exploded through spatial enablement of

systems. The land management paradigm allowed a focus on planning and

development for sustainability to come to the forefront at the stage

when information is collected and systems are designed. Modern land

administration systems are now required implement processes that deliver

sustainability, rather than provide information to government policy

makers so they can take this responsibility. Methodologies vary, but

always involve implementation of a set of formally organized tools that

perform processes essential in land markets and land policy

implementation. The tools, and the options available to implement them,

also vary and are increasingly examined as a theoretical set or suite.

Among the many suggestions, three examples are notable.

a) The narrowly defined traditional tools in a focused land

administration approach

- Land tenure and registration systems

- Land valuation and market systems

- Land development and planning systems

- Cadastral surveying and mapping

- Benchmarking and monitoring

These are the traditional tools of Geomatics, together with

specialist professional areas of valuation, planning and business

administration. In some countries all of these fall naturally under the

heading of land administration, but most countries have separate

professional groupings to attend to discrete functions. These

traditional tools remain the core of land administration endeavors,

though the selection of options actually used is now influenced by the

broader considerations of sustainable development, and good governance.

The fundamental lesson from the last 40 years of implementation of these

specialist tools is that no one solution is capable of being universally

used. The “one size fits all” solution, even in boundary establishment

and recognition, does not work. Now land administration experts design

their solutions for a country’s land administration requirements in the

context of its existing conditions, competencies and practices.

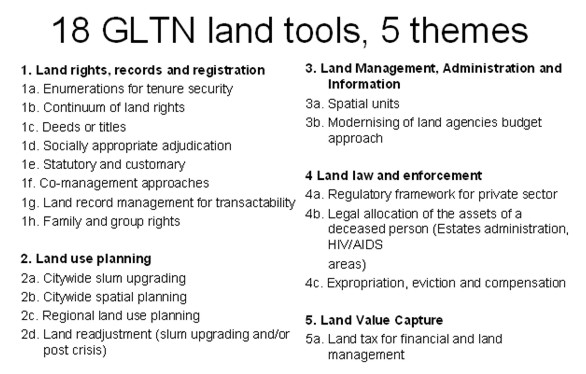

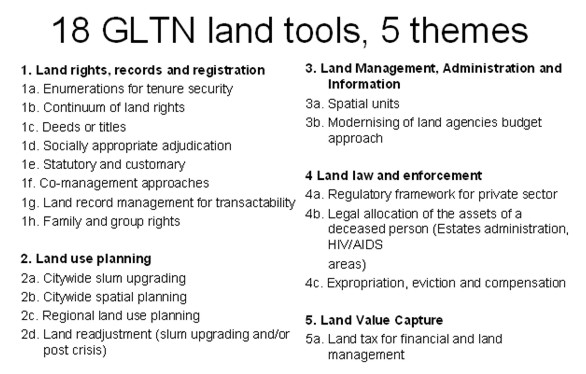

b) The 18 land management tools of Global Land Tools Network of UN

HABITAT in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. GLTN, HABITAT land tools

The GLTN suite of tools is designed to service pro-poor land needs,

not land markets per se. However, the tools are essential in pro-market

systems in developing countries where numbers of poor people and land

pressures over arch land policy and institutionalization of land

arrangements.

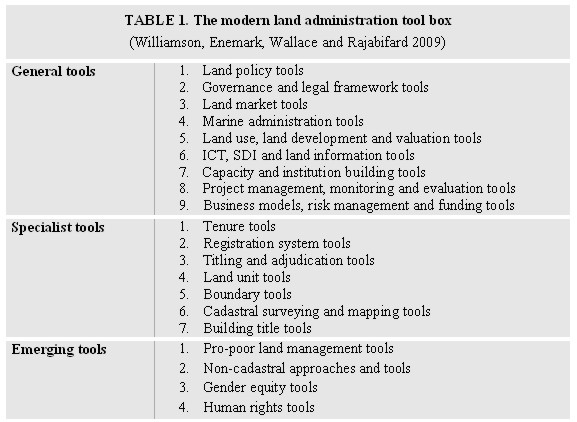

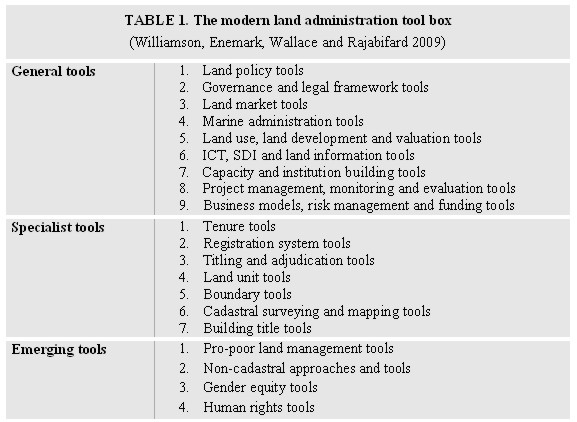

c) Tools to cover the range of issues faced by modern governments

This set of tools in Table 1 above builds on traditional land

administration thinking, and takes a long range view to setting up

sustainable systems of administration, implementing social, economic and

environmental land management, and retaining sufficient flexibility to

utilize the newest appropriate technologies if and when they appear.

This increasing use of tools, seen also in the parallel attempts to

institutionalize good governance standards in national administration,

is happily called “the toolbox approach”. The toolbox idea is both

fertile and easy to understand.

3. BUILDING LAND MARKET TOOLS

Toolboxes needed for modern land management share one thing. While

they do not demand a market approach be adopted for land distribution,

they do demand all decision-makers appreciate the difficulties and the

challenges involved in establishing systems to manage ordinary processes

related to local land. These three tool boxes acknowledge that land

markets involve processes that must be managed and seek to move

management from informal systems to formal sectors of government. They

all emphasise the fundamental starting points in design of any system

are existing public expectations and practices. Thus land administration

experts do not suggest that implementation of a tool or a suite of tools

will, of itself, deliver national capacity to manage a local land

market. To deliver a land market, the tools need to institutionalize a

national concept of property in land.

This property concept is complicated. But there is really no mystery

about it. Communities that understand this concept are ready for a

modern land market; others are not. Many previous attempts to introduce

markets involved constructing the land administration systems without

regard to the society’s capacity or willingness of intended

beneficiaries to use or relate to land markets, with unintended and

often negative consequences.

Institutionalization of property involves a tenure system (legal

tools, usually legislation) and a titling system (land measurement,

identification and management of transactions: typically through

registries and cadastres). Economic operation of land markets also

depends on related markets for agricultural products, labor, and money.

The inter-relationships between these markets will vary from

place-to-place and time-to-time. As we all know, these

inter-relationships are often unpredictable.

4. PROPERTY IN LAND ADMINISTRATION

The idea of “passporting” property is a major contribution of

Hernandes de Soto (2000) to our understanding of land markets. It led to

an assumption that passporting processes suitable for all nations could

be designed and implemented through top-down national policy and

development aid programs that emulated systems used in successful land

market countries. This proved much more difficult for reasons now

understood to relate to the need to base administrative or legal reforms

on the ideas of land that already operate in nation states, indeed even

in small areas within nation states. In short, the institution of

property is not transferable by introduction of technical and

administrative systems and processes – it must be built by people

themselves as they absorb the pressures of their lives and internalize

change.

Market systems rely on “private property”, an idea which emphasizes

only one side of the property function – identification of people with

control over interests. However, the property function required

articulation of fences around all human behaviour in relation to land

and opportunities (Reed 2003). In an ideal world, the property

institution would move the fence defining property units (or market

commodities) to ensure a balance between the various rights, including

the rights of the state, to facilitate land markets, sustainability and

land distribution reform. Adequate enforcement of private property would

allow people in control of other people’s resources to take only those

risks that they would take if they personally owned the resources. And

the property institution would incorporate the European,

inter-generational model of land exploitation by ensuring that public

interests in sustainable development were recognized (Raff 2003). The

ultimate justification for private property is the common good and thus

the applications of private property must ultimately be socially

defensible.

Another way of explaining this relies on legal theory. The lawyer’s

idea of property is a duality: it allows the owner of property (whether

the asset is tangible or intangible) power against all takers, with a

co-relative imposition of responsibility to respect this power on all

potential takers, including the state. The lawyer therefore requires

land administrators to design processes that respect the duality of land

rights. Rights always involve someone with power and someone with a duty

to respect the power. Whatever the legal theory (natural law,

empiricism, American legal realism, legal positivism, critical legal

theory, and so on), the duality remains. Thus the land administrator is

faced with not just tracking the owner, but with systematically

identifying whom in the socio legal order must respond to ownership and

how they must respond.

Lawyers also differentiate property rights from all other kinds of

legal rights: we notionally attach the legal right to the “thing” (which

may be abstract – such as a share in a company, or a debt, or freehold

ownership). Thus we are able to attach rights to an interest in land

irrespective of who owns the parcel and when they obtained their

interest. If the right relates to property interests in land, it

automatically binds subsequent owners. Thus property rights subsist

beyond the immediate parties who created them. Mere contractual rights,

by contrast, can be asserted only by the parties to the contract. This

is why banks and money lenders want “security” over the land when they

lend to home buyers and developers. And why a mortgage system needs to

deliver a proprietary right enforceable against all takers of the land

beyond the person who obtained the initial loan.

Any group of people who organise access to and distribution of their

land will use a theory of property. Organisation presupposes a system of

rules (Llewellyn 1940). Prior to this, the group will rely on exercise

of brute force or power to assert claims to possession. In practical

terms, a theory of property used in a nation is fundamentally connected

with the heritage of its system of rules, notably its law. For

convenience we can divide the world into seven anthropological legal

orders or “families”: Chthonic (recycle the World); Talmudic (Perfect

Author); Civil Law (Centrality of the person); Islamic (Law of a Later

Revelation); Common Law (Ethic of Adjudication); Hindu (The Law as King,

but which law; and Asian, (Make it New - with Marx) (Glenn 2004).

For land administrators diversity of legal origins poses a massive

problem of communication. Our individual familiarity with property

theory in our home jurisdiction undermines our ability to interpret the

idiosyncrasies of any other property theory. This is compounded by the

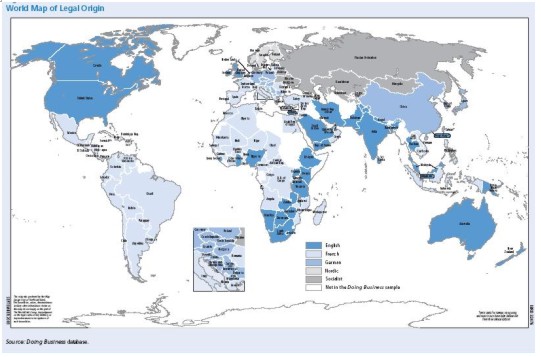

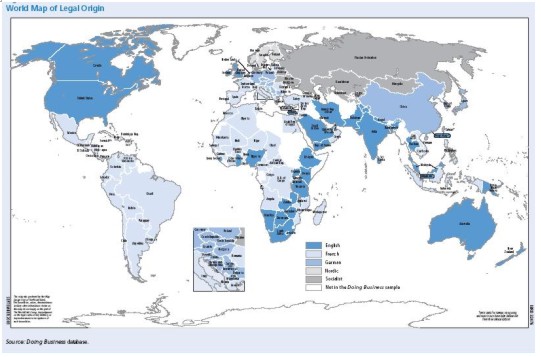

European influences in colonization shown in Figure 3 below which

created two mega families in the world finance, constitutional patterns,

and legal orders: the common law or British empire countries, and the

civil law countries.

Figure 3. World Bank map of legal origin, p 85.

From the land administration perspective, the major issue of

servicing land markets revolves around the quite different concepts of

land ownership, and hence property in land, in these two dominant legal

families.

Relative property theory. Common law countries have the

benefit of an open-ended and relativistic theory of property. To

illustrate (with over-simplification): in Australia, we can have three

perfectly sound, legally recognized owners of the same land at the same

time. The first is the legal owner (usually the registered owner with a

Torrens title). The second is the equitable owner (the person who

benefits from the land because the legal owner holds on a trust). The

third is the person who has possession of the land – if that person

holds on for a 12 (in most states) year period, the legal owner and the

equitable owner cannot reclaim the land. English trained lawyers are

therefore familiar with having multiple owners each holding a freehold

estate in land simultaneously recognized in a complex system of

priorities. The system requires complex priorities rules for its daily

operation. It is so complicated, that its inventor nation, England,

renovated it in 1925 by abolishing all its legal interests except

ownership and leases, including mortgages, through reforms that emanated

from one of the most conservative parliamentary institution in the

world’s history, the House of Lords. Ex colonial nations have tended to

preserve the old system in its full glory.

In Australia, perhaps the most counter-intuitive result of relative

property is the status of most owners of the legal freehold in valuable

land. A great deal of commercial, agricultural and industrial land is

owned by a legal owner who is a shell: the real owners are the

beneficiaries of hidden trusts. The state and the public at large do not

know about these trusts. They are not on the public record, and indeed

their registration is forbidden. The result is that land markets in

these Australian jurisdictions operate without the real owners of most

commercial land being on the public register, and without any adverse

implications for market operations. This is definitely not a system to

be emulated in other countries. However, it illustrates that markets can

be both transparent and effective for trading purposes without all

important interests being in a public register.

The idea of relative property in land also led to another notable

consequence: the English law recognizes the estate in land, not the

land, as the thing that is owned. Thus a tenant’s home can be burned,

but his lease still exists and his rent must still be paid. Flying

freeholds (with no “land” at all) were recognized in Australia with

ease, in the form of a building extending over a laneway, then in a

simple strata title system invented in the 1960s. Condominium owners

still own their estates despite destruction of the entire building. In

the cut and thrust of a robust property market, the relativities in

English influenced systems facilitated a stream of inventiveness that

demanded constant change in the legal and administrative systems.

Civil law systems. The property system in civil law is

different and recognizes a much more absolutist concept of owner, going

back to Roman law. Without the relativities, concepts such as trusts

which split ownership into two property rights (one legal and one

equitable), and then split ownership and management from benefits, must

be built by other methods, typically statutory. The concept of land is

rigid and recognition of the strata concepts is inhibited (Stoter 2004).

5. UNBUNDLING LAND

In modern land markets the number and nature of property based

commodities are unlimited. Since the mid 1990’s, new processes of

commodification are especially challenging for land management because

they involve “unbundling” land into separate commodities. Opportunities

related to the land itself, minerals and petroleum, water, fauna, flora,

tradable permits and credits in, for example, carbon credits, dry-land

salinity credits, planning opportunities, waste management rights, and

so on, are repackaged as tradable assets. The idea comes from using

market based instruments (MBI) or incentive instruments for environment

and resource management. These initiatives borrow heavily from property

theory and from the main characteristics of Western property:

exclusivity, duration, quality of title, transferability, divisibility

and flexibility. They all require an administrative infrastructure,

frequently incorporated into land administration, but sometimes built

separately. Analysis of infrastructure needed to manage these

commodities to date concentrates on registration, indefeasible title,

mortgageability, and compensation for acquisition. Overall, these

developments challenge a nation’s capacity to manage land holistically,

unless the design of the administrative arrangements and the information

generated are related back into LAS and land information. Moreover,

little theoretical or practical research is available on how to

incorporate social and stewardship values equivalent to the substantial

restrictions on land into these new commodities.

6. STAGES IN DEVELOPMENT OF LAND MARKET ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS

The land administrator needs to appreciate these fundamental

differences in the concept of property in land among these two legal

families and to skillfully unpack the threads of historical and social

development of any local property theory. The administrator also needs

to understand how to build supporting infrastructure to service markets

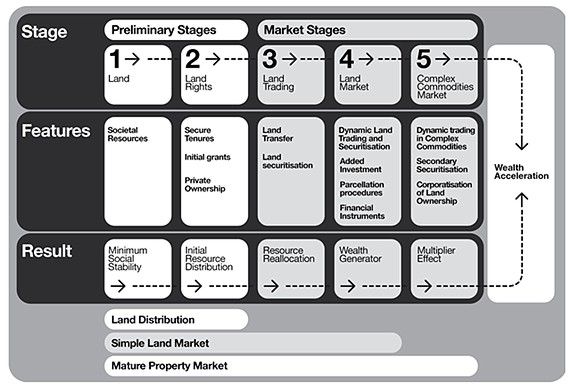

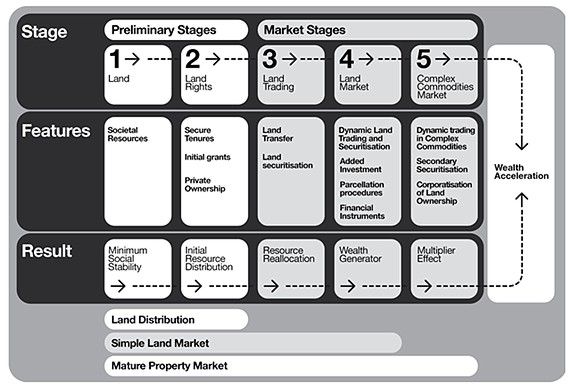

as they develop through stages. In Figure 4 below, an heuristic

(not empirical) set of stages is suggested to facilitate our

understanding of the functions that land administration systems need to

perform as they mature to meet modern land market needs (Wallace and

Williamson 2006).

Figure 4. Stages in land market development

An analysis of these stages is already available (Wallace and

Williamson 2006). While markets depend on capacity to define commodities

in the form of rights and interests that are recognised as property,

processes involved are typically mixed up with land trading and

marketing. For a country to achieve a land market, its policy makers

must obtain public commitment to the institution of property in land.

This involves creating rights and interests that stabilise land

distribution and generate capital. While land rights can exist without a

market, markets cannot exist without land rights. Tradable land rights

are the outcome of the institution of property. Robust land rights and

an effective LAS are necessary, though not sufficient, for success in

the later market stages.

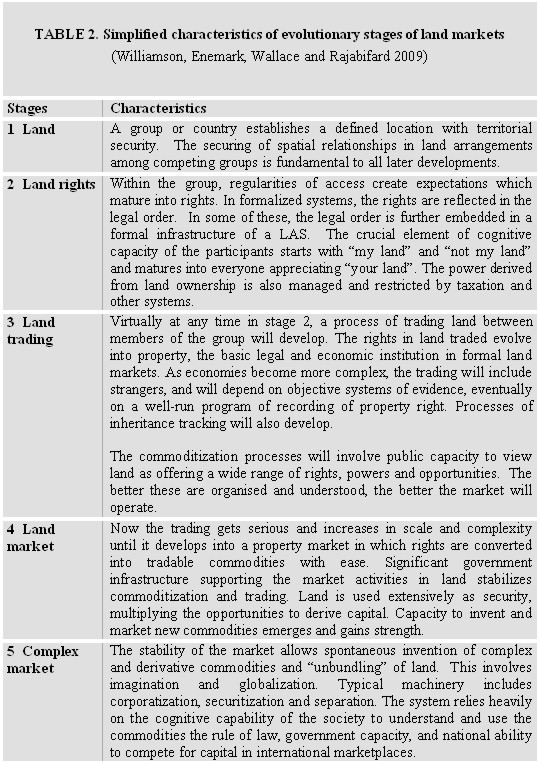

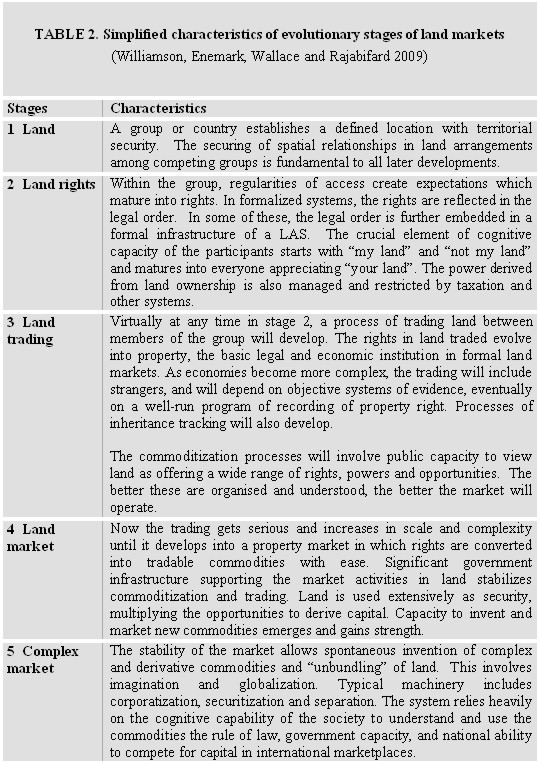

In order to explain these relationships and functions, Table 2

below provides a short introduction to the nature and content of each

stage. The important message is to understand that a system needs to be

able to move from a passporting land ownership to a passporting system

capable of generating complex cognitive commodities on an open-ended

basis, hopefully with the degree of regulation that ensures the various

interests remain in a socially and economically acceptable balance.

7. INSTITUTIONALIZING PROPERTY FOR EFFECTIVE LAND MARKETS

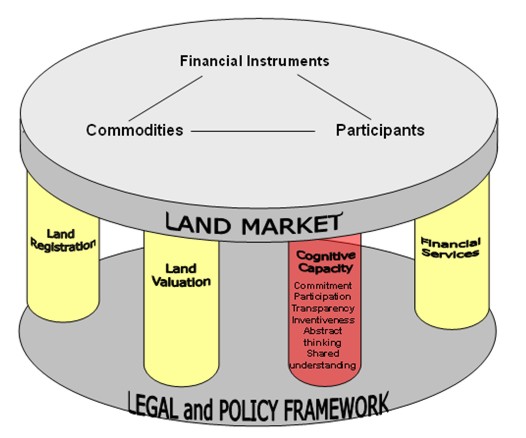

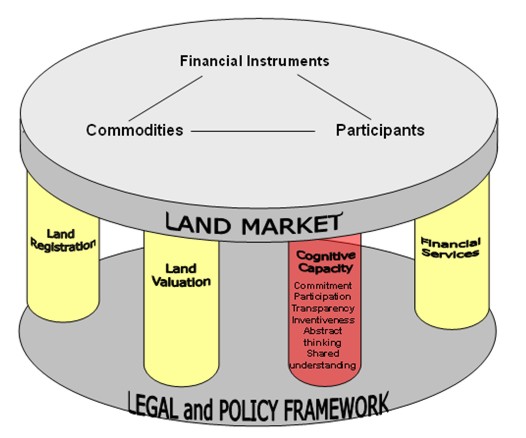

The most significant effort in developing land markets work must be

devoted to building the cognitive capacity of the public to

understand the market related concept of property (Figure 5

below). This remains essential even in centralist economies (for

example, in Vietnam and China) where land remains an asset of the

government for the benefit of all citizens. Thus systems that manage

land market processes must be built in the context of government

commitment to the public, and the co-relative commitment of people to

the formal processes. Otherwise they will boycott the formalities. The

formal processes must allow public participation, be transparent, allow

scope for private inventiveness and inclusion of new commodities. The

processes must facilitate abstract thinking and shared understandings of

the property model. And all of these must be achieved while respecting

local ideas of land and its significance to its users.

Figure 5. Cognitive capacity in land markets

(Wallace and Williamson 2006, based on Dale’s Three Pillars Diagram,

2000 P.IV)

8. CONCLUSIONS

The demands on land administration systems will continue to grow.

Their designers must anticipate sources of disputation and seek to

eliminate them, while addressing inevitable failures and disputes.

Articulation of public and private roles in relation to land must

encourage cooperation and sharing of common goals. Regulation, the rent

seekers’ bible, must be limited in favour of creativity and

inventiveness. Land administration systems need to be spatially enabled

to assist information sharing and streamlining of processes in

government, business and society at large. The historical constraints on

tenures need to be relaxed so that traditional and modern communal

systems are protected within a market context. Land administration

theory has evolved to define, if not meet, these issues. And hopefully,

the discipline now stands ready to meet the challenges of stabilizing

land market process to meet the pressures of global economic recession

by preserving and enhancing the social utility of our property

institutions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The teamwork of staff and students at the Centre for Spatial Data

Infrastructures and Land Administration underlies this paper,

particularly Rohan Bennet, Kate Dalrymple and Mohsen Kalantiri (whose

PhD theses are on the centre’s website:

www.csdila.unimelb.edu.au).

Acknowledgment is especially due to my coauthors of a forthcoming book

on land administration, Ian Williamson, Stig Enemark and Abbas

Rajabifard. Any errors are the fault of the author.

REFERENCES

Cohen, Felix, 1954, Dialogue on Private Property, 9 Rutgers

Law Review 357.

Dale, P. 2000, The importance of land administration in the

development of land markets: A global perspective, in Land

Markets and Land Consolidation in Eastern Europe,

http://www.landentwicklung-muenchen.de/aktuelle_aufsaetze_extern/seminar_04.pdf

De Soto, Hernandes, 2000, The Mystery of Capital. Why Capitalism

Triumphs in the West and fails Everywhere else, Bantam Press,

London.

Enemark, Stig, 2006, The land Management Paradigm for

Institutional Development, in Williamson, Ian, Stig Enemark and Jude

Wallace (eds), Sustainability and Land Administration, Department

of Geomatics, Melbourne. Pp17-30.

Glenn, Patrick, 2007, Legal Traditions of the World,

Sustainable Developments in Law, 3rd ed. 2007 Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

North, Douglass. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and

Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Raff, M. (2003) Private Property and Environmental Responsibility:

A Comparative Study of German Real Property Law, Leiden, The

Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Reed, O. Lee, 2003, Reductionism in Property, Liberty, and

Corporate Governance, 36 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law

367.

Stoter, Jantine E. 2004, 3DCadastre, Geodetic Commission, The

Netherlands.

Wallace and Williamson, 2006, Building Land Markets, Land

Use Policy Journal,

Williamson, Enemark, Wallace and Abbas Rajabifard, 2009

(forthcoming), ESRI Publications, San Diego.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Jude Wallace is a land policy lawyer and researcher. She works

in international land administration, dealing with systems to deliver

social, environmental and economic sustainability. Her policy analysis

spans all land tenure types used by the world’s people, all methods of

securing access to land and resources and the expanding opportunities

created by new technologies.

Her research includes designing modern land administration systems

for complex property markets, betterment systems for rural land tenures

systems, and modeling of processes and transactions associated with

social transitions and land markets. Her international consultancy work

includes projects in Australia, United Kingdom, Indonesia, East Timor,

Vietnam and Iran. As Law Reform Commissioner for Victoria she worked on

reforms of land law and administration, mining law, and subdivision law

and procedures.

CONTACTS

Ms. Jude Wallace

Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration

Department of Geomatics

The University of Melbourne

Melbourne

AUSTRALIA 3010

Tel. + 61 3 8344 3427

Fax + 61 3 9347 2916

Email:

j.wallace@unimelb.edu.au

Web site:

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/people/jwallace.html

|