Article of the Month -

November 2013

|

Boundary Makers: Land Surveying in nineteenth-century,

New Zealand

Professor Giselle BYRNES, Charles Darwin University,

Darwin, Australia

1) Surveyors around the world

are struggling with many current challenges. However, this article gives

you a possibility to reflect about the impact of surveyors through

history in the development and mapping of societies. This paper is a

historical outline of the early land surveyors importance to the history

of New Zealand, as they were among the advance guard of European

settlers to walk the land and assess its potential for future

development. Surveyors around the world are struggling with many current

challenges. However, this article gives you a possibility to reflect

about the impact of surveyors through history in the development and

mapping of societies. The paper is a historical outline of the early

land surveyors importance to the history of New Zealand, as they were

among the advance guard of European settlers to walk the land and assess

its potential for future development. We are pleased to share this paper

with you since FIG Institution for the History of Surveying and

Measurement organises a very special trip, conference and event on

Charting and Mapping the Pacific Paradise of the Pitcairners at

Norfolk Island, (an island half way between Australia and New Zealand),

6-10 July 2014:

Invitation

and

program.

A version of this paper was presented to Celebrating the Past -

Redefining the Future, New Zealand Institute of Surveyors

Conference, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 27-30 August

2013. In addition, much of this essay is drawn from Giselle Byrnes,

Boundary Markers: Land Surveying and the Colonisation of New Zealand,

Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2001; see also G. Byrnes, ‘Surveying—Maori

and the Land: An Essay in Historical Representation’, New Zealand

Journal of History, vol. 31, no. 1 (1997), pp. 85-98. See also Giselle

Byrnes, ‘Boundary Makers: Land Surveying in 19th Century New Zealand’

in Mick Strack, ed., Survey Marks: A 2013 Celebration, School of

Surveying and the New Zealand Institute of Surveyor, Dunedin, 2013, pp.

7-16.

Key words

Land surveying, colonisation, Maori land, land

settlement

ABSTRACT

Land surveyors in nineteenth-century colonial New

Zealand were located, quite literally, at the ‘cutting edge’ of the

great British imperial project to claim and tame new territories. The

early land surveyors were important actors in this country’s history as

they were among the advance guard of European settlers to walk the land

and assess its potential for future development. Indeed, the landscape

of modern New Zealand testifies to their work through the place-names

they assigned and which are still visible on the map. Moreover, most

colonial land surveyors were aware that they were not ‘first-time

explorers’, but were traversing landscapes that were already known,

named and mapped by the indigenous Maori. In the early period of

organised British settlement, from the 1840s to the 1860s, the land

surveyors’ efforts to claim the land were, therefore, much less an

exercise in possessing the land outright than they were translating the

meaning of land from one cultural framework into another. From the

1860s, however, and especially with the aggressive activities of the

Native Land Court from 1865, the work of the colonial land surveyors

took on a more potent role as Maori land was permanently transitioned

from customary tenure to Crown-derived titles and subsequent private

ownership. This essay briefly considers the colonising efforts of the

early colonial land surveyors in New Zealand during the second half of

the nineteenth-century following the assertion of British sovereignty

1840 and their negotiation of both the cultural and physical boundaries

they encountered during the conduct of laying out the land for future

settlement.

NEW ZEALAND, an isolated archipelago located

some 1500km east of Australia in the south-west Pacific, was one of the

last substantial landmasses to be settled by humans. While the

Polynesian ancestors of the indigenous Maori people arrived on the North

and South Islands over 1000 years ago, the European settlement of New

Zealand occurred much later. Although there was intermittent contact and

trade between Europeans and Maori from the late eighteenth century, it

was not until the 1830s that the British began to assert their presence

in New Zealand, mainly through missionary efforts to ‘convert’ Maori to

Christianity, led by the London-based Church Missionary Society. In

February 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between the British

Crown and Maori tribes whereby, and despite serious ambiguities between

the intent and meaning of the Maori and English language versions of the

Treaty, the British assumed sovereignty over the country and declared

New Zealand a Crown colony. Massive British and European immigration

immediately ensued and within a decade war over land and issues of

sovereignty broke out. For much of the remainder of the nineteenth

century, the colony of New Zealand was a war-zone with British colonial

forces embroiled in a bitter contest with indigenous Maori for control

of large parts of the country. Eventually, the British declared

themselves victorious and as punishment, much of the remaining land

occupied by Maori tribes was confiscated, following punitive models that

had been applied by the British in subduing the ‘rebel’ Irish clans in

the seventeenth century. In addition, successive New Zealand colonial

governments worked to redefine, control and ultimately transform the

meaning as well as the ownership of Maori land through a series of

complex legislative instruments. In this way, almost all of the Maori

land estate had passed out of indigenous hands by the early years of the

twentieth century. Today, just a small fraction of the original Maori

estate remains in Maori ownership (1).

The colonial land surveyors were critical to this

history of contest and transformation. Located among the vanguard of

European settlers to New Zealand, land surveyors were charged with

creating new outposts of empire that would replicate the values,

attitudes, and aspirations of the Old World. Moreover, the work of the

land surveyors reflects much that is central to the European history of

New Zealand, particularly the transformation, domestication and ‘taming’

of the natural environment. Physically located on the margins of settler

society, the land surveyors occupied a central role in implementing

colonisation on the ground. They were therefore both boundary markers

as well as boundary makers.

SURVEY METHODS AND PRACTICE

The task of the colonial land surveyor was a

significant one. Charged with reining in the wilderness and creating

order and sense in ‘uncharted’ territory, the land surveyors occupied a

peculiar position in the practical implementation of colonial policy.

The lines inscribed by the land surveyors—in maps, drawings and plans as

well as on the land itself—were symbols of power and portents of the

political, social and economic change that was to follow in their wake.

In this way, land surveying was fundamental to the British acquisition

of new territory, and represented, in a very graphic and visible way,

the thrust of the broader colonial project.

Land surveying in colonial New Zealand had its

genesis of course in a much older tradition. In the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, the expansion of empires, along with the

consequent need to delineate national boundaries and construct maps of

territorial possession, demanded increasingly accurate methods of land

demarcation and measurement. In addition, the process of enclosure and

the increasing value of private property in rapidly developing urban

centres brought surveying and surveyors into the economic as well as the

political arena. By the middle of the nineteenth century, in Europe at

least, land survey methods comprised a combination of perspectives and

competing practices. While the influence of military techniques

(inherited from the Roman architects of land surveying) remained strong,

this was accompanied in the latter half of the nineteenth century by a

new emphasis on scientific engineering as a direct consequence of

British industrialisation.

TYPES OF SURVEYS

Broadly speaking, land surveys in colonial contexts

fell into two categories. The first involved confirming an already

existing cadastre and provided a retrospective vision of land already

settled; this was the case where the settlement patterns had long been

shaped by history and tradition. The second was concerned with the

future rather than the past; focussed on providing a framework for

future resettlement. This latter method, what might be termed the

'survey of the future', was enthusiastically adopted in New Zealand,

where the land surveyor's chief task was to layer a new spatial order on

the existing landscape. Within this ‘future’ survey, there were two

forms: those where the free selection of land parcels had commenced

prior to actual settlement and those where settlement was consciously

planned in advance. The 'free selection survey' was the most frequent

type of survey in colonial New Zealand, at least in the early years of

organised settlement. This allowed individuals to determine the

boundaries of their own allotment and frequently led to irregular and

odd-shaped parcels of land (along with the consequent administrative

confusion). On the other hand, surveyors who determined the shape of

sections in advance of formal occupation usually laid out a planned

settlement for clients such as individual landowners, a company or the

government. Free selection prior to survey can still be seen in the

design of many rural sections, while the New Zealand Company settlements

(the New Zealand city of New Plymouth, for example) are perhaps the best

examples of the planned settlement surveys. In their work, New Zealand

colonial land surveyors employed instruments which were common to

surveying practice elsewhere, including the theodolite, the

circumferentor or surveyors’ compass, and the prismatic compass (2).

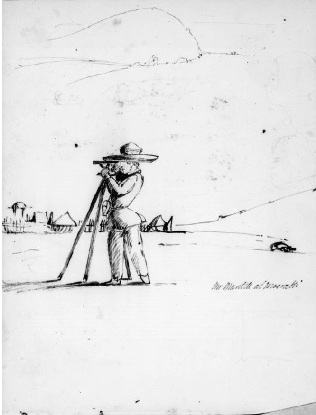

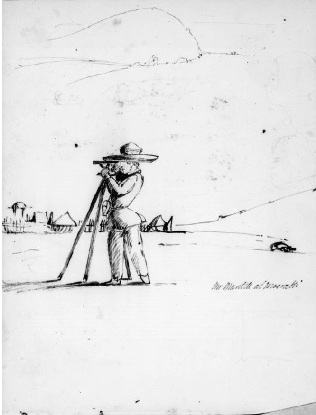

Francis Edward Nairn, ‘Mr Mantell at Moeraki [1848]’, ink on sketchbook.

E333-084-3, Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New

Zealand/Te Puna Matarauranga o Aotearoa.

THE COLONIAL LAND SURVEYORS

So who were these men and how might they best be

described? The land surveyors in colonial New Zealand worked in a number

of different capacities. From 1854 surveyors were included on the staff

of the Land Purchase Department (incorporated into the Native Department

in 1885), established to manage the acquisition of Maori land. Until

1862 it was possible to obtain work as a land surveyor without

registration, although surveyors under contract to the Crown to survey

Crown lands (and so-called ‘waste lands’) were required to satisfy the

standards set by the provincial chief surveyors. In the absence of a

standardised system of registration, any person with a minimum knowledge

of surveying could practice with minimal experience or qualifications.

Consequently, many young men turned to surveying as a relatively easy

source of income and adventure.

Following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and

the assumption of British sovereignty, increasing numbers of British

settlers arrived in New Zealand. With expectations about the superior

quality and potential of the land, the pressure for land quickly

intensified and the demand for surveyors consequently grew. During the

1840s, tension between the nascent colonial government and the New

Zealand Company over disparate land policies, together with the demands

of Company settlers, who felt cheated of their purchases, stretched the

existing resources of both the New Zealand Company and Crown survey

services. Sons of missionaries and traders, many of whom were educated

in mission schools and were fluent in the Maori language, were readily

recruited as surveyors. It is worth noting that their intimate knowledge

of Maori culture and language proved invaluable not only in negotiating

the survey, but also in facilitating the purchase of much of the Maori

land estate. With the further influx of settlers in the 1850s and 1860s,

the colonial government increasingly looked to the immigrant population

for additional survey staff.

Most but by no means all of the early surveyors were

born in England and made New Zealand their adoptive home. Some came from

Scotland and Ireland, while others came from further afield,

particularly central Europe. A large number of land surveyors had spent

time in the Australian colonies before arriving in New Zealand; indeed,

most of the early surveyors who have left records had travelled

extensively before arriving in the colony. Some had left established

careers to immigrate and brought experience with them, while others were

young men who chose to ‘cut their teeth’ in developing a surveying

career in New Zealand. Robert Park and John Rochfort, for instance, were

trained in engineering; Charles Heaphy initially trained as a

draughtsman; and Theophilus Heale, later chief surveyor and inspector of

surveys, was educated as a classical scholar, mathematician and

navigator. Some—Charles Heaphy, Samuel Brees and John Buchanan, for

instance—were highly accomplished artists, while others had trained as

draughtsmen and drew on these technical skills in the course of their

surveying fieldwork. Others became active in political roles, at both

the provincial and national level. Frederick Carrington, for example,

was a provincial superintendent and a Member of the New Zealand

Parliament. Land surveying was often a natural choice of occupation for

those young male settlers who could make use of their skills in a

particularly practical fashion. In addition, the colonial land surveyors

were often men of learning and intellectual ability, with interests in

poetry, ethnology, philology and geology. It would be fair to say too

that land surveying, due to its physical rigors, typically attracted

young men with a keen sense of adventure and an abundance of energy. For

many young men, a surveying career also promised the challenge of

working on the colonial frontier (3).

Two descriptions of the colonial land surveyors

vividly depict their appearance and countenance. The first is the young

Edward Jerningham Wakefield's colourful impression of meeting a group of

survey cadets in 1845 and is worth citing at some length. ‘I met two or

three of these [cadets] on the Porirua road’, Wakefield recalled, 'with

labourers and theodolites and other baggage, starting for the Manawatu

[a region of New Zealand]. I remember laughing at their dandified

appearance and wondering what new arrivals had thus suddenly taken to

the bush’. Wakefield was amused (and possibly irritated) by what he saw

as their youthful exuberance and highly affected appearance. 'Everything

about them was so obviously new; their guns just out of their cases

fastened across tight-fitting shooting jackets by patent leather belts;

their forage caps of superfine cloth; and their white collars relieved

by new black silk neckerchiefs. … Some positively walked with gloves and

dandy-cut trousers,' he continued, 'and, to Crown all, their faces shone

with soap. There had been a little rain the night before and, having

only got about two miles from the town, they were still picking their

way and stepping carefully over the muddy places.' Wakefield, with

first-hand experience of the hardships of colonial life, knew these

efforts at cleanliness and respectability would be short-lived. 'I sat

down on the stump of a tree', he concluded, 'and vastly enjoyed the

cockney procession; wondering how long their neat appearance and

fastidious steps would last.' (4)

John Turnbull Thomson's description of the colonial

surveyor provided a startlingly contrasting picture that emphasised the

egalitarian nature of life on a survey team. 'The Colonial Surveyor', he

wrote, ' ... is clothed in fustian trousers and blue shirt, Panama hat,

and stout hob-nailed shoes. He is not known from his chainman. If he

smokes, it is … through a "cutty" pipe, and he puffs at that

energetically.' Thomson's surveyor was not only resourceful, but a

jack-of-all-trades: 'He has a hundred things about him; knives, needles,

telescopes, matches, paper, ink, thread and buttons; these are stowed

away in all corners of his dress; and then his "swag" contains his tent,

blankets, and [a] change of clothes.' Thomson’s surveyor was also a man

of the land. 'These [items] with his theodolite he carries on his back,'

Thomson went on to say, 'and walks away through bogs, "creeks", and

scrubs, at the rate of 3 miles an hour. He cleans his shoes once a month

with mutton drippings, and he lives on "damper", salt junk and oceans of

tea. His bed is on the ground, and he considers himself lucky if he gets

into a bush where he can luxuriate in the warmth of a blazing fire.'

Thomson's was also a man with certain qualities and precious skills. 'In

this land of equality he shares bed and board with his men,' he

observes, 'but they are not of the common sort, for "the service" is

popular among the enterprising colonists, and he has to pick. They are

men that know their place and their duty ... I prefer the homely

enjoyments of colonial life.' (5)

The everyday reality for the colonial land surveyor

was clearly challenging and probably sat somewhere between these highly

romanticised images. The rain, 'the bog' and the inclement weather

elicited frequent comments and complaints. Generally, the climatic

challenges, while inconvenient, were seen as a test of strength and

fortitude. 'The [New Zealand] Company's surveyors whose life is almost

wholly spent in the bush,' Charles Heaphy remarked in 1842, 'and who

often pursue their vocation in all weathers, are amongst the healthiest

and most robust men in the colony.' (6) They had to be able-bodied and

strong, as living arrangements were often makeshift, temporary and

haphazard, and often fraught with risk.

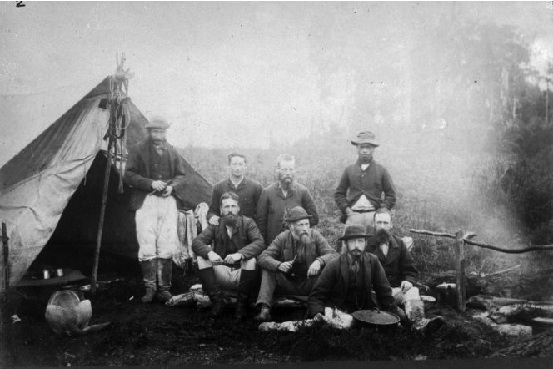

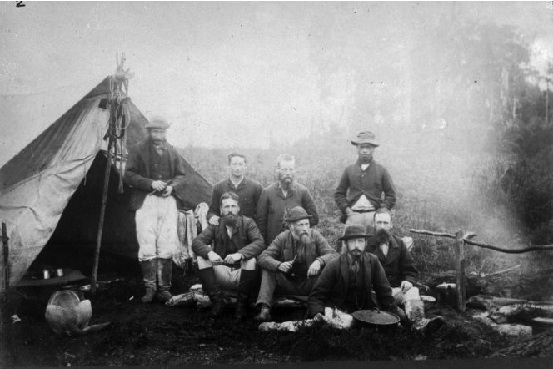

’Stephenson Percy Smith and his survey party’, black and white

photograph, ½-061056, F, Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of

New Zealand/Te Puna Matarauranga o Aotearoa

NEGOTIATING CULTURAL BOUNDARIES

Despite the aggressive pace of the British

colonisation of New Zealand post-1840, most of the early colonial land

surveyors were keenly aware that they were not ‘first-time’ explorers,

but were traversing landscapes that were already known, named and mapped

by indigenous Maori. Certainly, from the 1840s through to the 1860s the

land surveyors’ efforts to name, tame and claim the land were much less

an exercise in possessing it outright and more about transitioning the

meaning of land (its value, attributes and qualities) from one cultural

framework to another. From the 1860s, and especially with the operation

of the Native Land Court from 1865 onwards, the work of land surveyors

took on a more formidable role as Maori land was transferred from

collective customary tenure to individual Crown-derived titles and, in

many cases, was permanently alienated. This meant that land surveyors

were in frequent contact and negotiation with resident Maori

communities; indeed, for many communities, the land surveyor was the

‘face’ of the new colonial order.

Fortunately, many of the early land surveyors

recorded their contact with Maori in great detail, often acknowledging

their dependence on their Maori assistants, cooks and chainmen. The

early land surveyors also noted that Maori survey hands—accurately

referred to by surveyors as 'the compass'—were especially valued for

their navigational skills. Indeed, Maori often proved more able than

European assistants. John Rochfort, who surveyed in the Nelson and

Canterbury provinces in the South Island during the 1850s, chose to

employ only Maori survey hands. While surveying the boundaries of the

Canterbury and Otago provinces in 1858, Edward Jollie wrote how he 'took

an old Maori with me named "Governor Grey", who had lived for some time

in the Wanaka District' and the ways in which he relied upon this

particular guide. Women, too, worked in this capacity. In January 1844,

when Jollie travelled from the Manawatu River [in the North Island] back

to Wellington, he and his party 'secured a canoe to take us the first 12

miles of our journey, the crew consisting of two Maori girls'.(7)

Maori responded to the increased demand for their

services from the land surveyors by adapting and expanding their

existing economic networks. Arthur Dobson, for instance, wrote that on

the West Coast of the South Island, 'as time went on able-bodied young

men that I had working for me sent word to the various pas (Maori

village settlements) down the coast that I was coming, and that I would

pay for help for canoeing on the rivers'.(8) When Dobson arrived to

commence his survey, members of the local tribe Ngai Tahu, were ready

and waiting for business.

Maori employed as guides for the colonial land

surveyors therefore played a contradictory role in the surveying and

exploration of New Zealand. These contradictions were particularly acute

when European explorer-surveyors paid indigenous Maori guides, who were

already familiar with the area, to assist them in their 'discovery'. In

the Australian context, Henry Reynolds has considered how European

explorers used Aboriginal guidance to ‘open up’ much of the Australian

continent to European settlement. Paul Carter has also observed how in

Australia the European explorer was more often led than leader. Apart

from complicating what we mean by the term ‘exploration’ in the early

colonial period, this engagement clearly posits Maori and other

indigenous actors as active, rather than passive players in the larger

colonial project.(9)

The negotiation of this sort of boundary making

eventually cut both ways, however, and Maori opposition to surveying was

not uncommon as lines were drawn, often arbitrarily, through

cultivations and across tribal boundaries. Indeed, from the 1860s

onwards, for many Maori communities the presence of the land surveyor

became a metaphor for loss and a portent of impending land alienation.

According to land surveyors who worked in Taranaki [in the southern

North Island], Maori frequently (and publicly) demonstrated their

opposition to the conduct of land surveys. While laying out the

settlement of New Plymouth, a New Zealand Company settlement in the

lower North Island Taranaki region during the early months of 1841,

Frederick Carrington was confronted by 'natives from the interior who

said we that we should not cut any more. They flourished their

tomahawks, and danced and yelled, and I thought we should all be

massacred.'(10) In Taranaki, this reaction was not surprising, given

that many of the purchases were highly contested, both at the time, and

later, in the form of submissions to successive government commissions

of inquiry. Tensions between the Ngati Toa tribe and the New Zealand

Company land surveyors working at Wairau, near Nelson in the north of

the South Island, reached a climax in June 1843, when 22 settlers and

six Maori were killed. The incident followed an attempt by officials of

the New Zealand Company in Nelson to seize by force land from the great

rangatira (chief) Te Rauparaha, who denied having sold the land.

For Maori, the surveyor's theodolite—commonly

referred to as the 'taipo' or 'tipo'—was also a symbol of uncertainty

and possible conflict. From the 1840s, the erection of survey poles,

like the traditional pou whenua marker-poles of Maori society, signified

an explicit and aggressive act of possession. Maori leaders therefore

often regarded the intrusion of the surveyors and their boundary markers

as overt challenges to their mana. While surveying Ngai Tahu land

reserves in the South Island in September 1848, the surveyor Walter

Mantell noted how '[t]wo or three old men not understanding the erection

of a pole at their huts at Waitueri threw it away with the others which

the man carried. I went down [and] lectured them [and] explained the use

of the pole and remained there.'(11) There is much evidence to suggest

that Maori well understood the erection of the survey poles, and their

removal was a deliberate act of protest at Mantell's marking out of the

reserves. The surveyor Edwin Brookes cited the suspicion Taranaki Maori

held towards the theodolite in the 1870s: 'The invariable expression

that would come over them after a long drawn breath was "taipo", meaning

evil spirit: by my interpretation was—a mystery, or something

mysterious. In order to show them a friendly spirit, I would allow many

of these natives to look through the telescope, when they would withdraw

from it much perplexed.'(12) While impressed by the technology, Maori no

doubt appreciated the powerful role of the theodolite in the survey and

alienation of their lands.

The initial phase of breaking in the land,

establishing European settlements and striving for political dominance

led to increasing tension between Maori and surveyors. According to the

records created by the land surveyors themselves, resistance from Maori

towards the progress of surveys continued well into the latter half of

the nineteenth century. Under the instructions of Wi Kingi Te Rangitake,

for instance, women pulled up the survey pegs at Waitara [near New

Plymouth] in February 1860 to demonstrate their opposition to the survey

of what is now considered to be a highly disputed 'purchase'. In other

parts of Taranaki there were frequent incidents of antagonism between

Maori and surveyors. While laying out military settlements in north

Taranaki during 1865-66, Stephenson Percy Smith worked under the

protection of armed military covering parties. Given that Smith's

surveying work was part of implementing the punitive policy of land

confiscation (the raupatu), it seems hardly surprising that Maori

directed their frustration at surveyors, the most visible agents of this

pernicious policy.(13)

These examples of conflict serve both to illustrate

the precarious position occupied by the early land surveyors working in

the field and highlight how an indigenous Maori system of naming and

mapping pre-dated and indeed co-existed with the new order imposed by

the colonial land surveyors. For Maori, boundaries on the land formed

the basis of an indigenous system of mapping. As the basis of tribal

economy and community life, land was identified through a complex system

of rights and privileges that relied on physical as well as cultural

boundary markers. While whakapapa (genealogical) connections, waiata

(song), and 'mental maps' were used in navigating the land, boundaries

were indicated by geographical features such as hills, rock formations

and rivers. Stones, wooden posts and holes dug into the ground also

functioned as markers between tribal areas, and individual cultivation

plots were often the most enduring divisional marks. Maori also diverted

streams and constructed estuarine canals to assist with fishing and to

act as boundary markers. Prior to organised British settlement in the

mid nineteenth century, there was little need to precisely delineate

physical boundaries. From that point forward, however, boundaries on the

land became symbols of identity, ‘ownership’ and esteem; established and

legitimized in public and official discourse and given popular currency

by government legislation. Western capitalist ideas of land tenure and

individual property ownership then quickly dominated. The land wars, and

their issue—the Native Land Courts and the raupatu—also played a role in

this fundamental shift in thinking. While indigenous Maori perceptions

of land use and ownership continued, European (and especially British)

ideals about land usage and administration soon became the norm rather

than the exception.

CONCLUSION

While much of the map of modern New Zealand is

testimony to the work of the early colonial land surveyors, they have

been largely overlooked as a founding group of colonists in this

country’s history. Notwithstanding a few recent publications that have

attempted to remedy this oversight, it is something of a paradox that

while the dominant story of New Zealand has written them out of history,

the land surveyors themselves had been actively engaged in writing

themselves in. Their legacy lives on in placenames that survive as

historical artefacts from another era. Indeed, in almost every corner of

contemporary New Zealand, the land surveyors’ names and descriptors can

be found in geographical features, suburbs, districts and even streets.

Finally, the diaries and field books of the colonial land surveyors

offer valuable evidence to the interested reader. As well as containing

technical details regarding the conduct of early land surveying, these

records reveal rich and detailed botanical and ethnological information

as well as personal reflections on the processes of land transformation

and settlement.(14)

Land surveying was fundamental to the British

colonizing vision and the acquisition of new territories, such as New

Zealand, for settlement. The work of the colonial land surveyors

reflects much that is central to the history of New Zealand,

particularly the transformation and domestication of the natural

environment. The land surveyors were crucial in effecting change, as

they occupied a central role in implementing the principles of

colonization on the ground: they operated, quite literally, at the

‘cutting edge’ of colonization. Their work deserves, therefore, to be

remembered, though it also needs to be understood in context. While it

would be tempting to oversimplify the contribution of the land surveyors

to New Zealand’s past, and (depending on your point of view) to either

valorize or demonize their work as colonial entrepreneurs, it is worth

remembering that the land surveyors were agents of their time who were

capable of questioning the longer-term outcomes as well as the immediate

impact of their work. We need to remember them as complex historical

actors whose work has shaped the contours of our historical trajectory

and fashioned our modern society in ways more powerful than we fully

realize.

ENDNOTES

-

Land alienation, in addition to a range of other

issues, is the subject of the vast majority of claims by modern

Maori to the Waitangi Tribunal, a commission of inquiry established

in 1975 to inquire into the allegations by Maori tribes that the

Crown has consistently failed to honor its responsibilities under

the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. See further, Claudia Orange, The

Treaty of Waitangi, Allen and Unwin, Wellington, 1987; Alan

Ward, An Unsettled History: Treaty Claims in New Zealand Today,

Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 1998; Giselle Byrnes, The

Waitangi Tribunal and New Zealand History, Oxford University

Press, Melbourne, 2004.

-

Surveying in North America embraced both types of

survey, while in the Australian colonies, planned rectilinear (or

equal square) land division was the most common practice. Chain

surveying was also a common practice, where the Gunter’s chain,

66-foot long and divided into equal links, was used for calculating

distance.

-

John Rochfort, The Adventures of a Surveyor in

New Zealand and the Australian Gold Diggings, London, 1853.

-

Edward Jerningham Wakefield, Adventure in New

Zealand, first edition John Murray (ed.), London, 1845, revised

edition Joan Stevens (ed.), Auckland, 1975, pp. 233-34.

-

John Turnbull Thomson, ‘Extracts from a journal

kept during the reconnaissance survey of the southern districts of

the province of Otago’, in Nancy Taylor (ed.), Early Travellers

in New Zealand, London, 1959, p. 347. See also John Turnbull

Thomson, MS-Papers-0176, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, and

John Turnbull Thomson, Rambles with a Philosopher, Dunedin,

1867.

-

Charles Heaphy, Narrative of a Residence in

Various Parts of New Zealand, London, 1842, p. 23.

-

Rochfort, The Adventures of a Surveyor;

Jollie wrote 'this old Maori was named after Sir George Grey the

Governor—twice—of New Zealand, by I believe, Mr Walter Mantel

[sic].' Edward Jollie, Reminiscences 1825-94, MS-Papers-4207,

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, p. 27. Similarly, the wives

of Kehu and Pikewate joined them in guiding Thomas Brunner down the

West Coast of the South Island on his 'Great Journey' of discovery

in 1846-48.

-

Cited in Arthur Dudley Dobson, Reminiscences

of Arthur Dudley Dobson, Engineer, 1840-1930, Christchurch,

1930.

-

Henry Reynolds, 'The land, the explorers and the

Aborigines', Historical Studies, vol. 19, no. 5 (1980), pp.

213-26; Paul Carter, The Road to Botany Bay: an essay in spatial

history, London, 1987, p. 340.

-

F. A. Carrington, cited in William H. J. Seffern,

Chronicles of the Garden of New Zealand Known as Taranaki,

New Plymouth, 1896, p. 47.

-

Walter Mantell, 'Journal Kaiapoi to Otago,

1848-49', MS-Papers-1543, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

-

Edwin Brookes, Frontier Life: Taranaki, New

Zealand, Auckland, 1892, pp. 38-39.

-

The confiscation of Maori land, or raupatu, was

ushered in under the rather euphemistically titled ‘The New Zealand

Settlements Act 1863’.

-

As Nola Easdale has shown in New Zealand and

Stephen Martin for Australia, surveyors’ diaries and field books are

particularly rich historical sources. See further Nola Easdale,

Kairuri, the measurer of land: the life of the nineteenth century

surveyor pictured in his art and his writings, Highgate/Price

Milburn, Petone, 1988; Stephen Martin, A New Land: European

perceptions of Australia, 1788-1850, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards,

New South Wales, 1993.

BIOGRAPHY

Professor Giselle Byrnes is Pro

Vice-Chancellor of the Faculty of Law, Education, Business and Arts at

Charles Darwin University. Professor Byrnes moved to the Northern

Territory from New Zealand in mid 2011 with her family to take up this

role. She was formerly Professor of History and Pro Vice-Chancellor

(Postgraduate) at the University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

(2007-2011).

Giselle Byrnes completed a PhD in History at the

University of Auckland in the mid-1990s and then worked as an historian

for the Waitangi Tribunal. She returned to academia in 1997 and taught

in the Department of History at Victoria University of Wellington for a

ten-year period (1997-2007). Here she established the Public History

programme and developed a suite of courses in social and cultural

history, with a particular emphasis on exploring history in colonial and

postcolonial contexts.

Professor Byrnes' publications include Boundary

Markers: Land Surveying and the Colonisation of New Zealand (2001), The

Waitangi Tribunal and New Zealand History (2004) and The New Oxford

History of New Zealand (2009), for which she was Editor. She has also

published numerous articles on various aspects of colonial, settler and

Indigenous histories, in addition to public history. While the focus of

her work has been grounded in New Zealand historical experiences, she

has expertise in comparative colonial and transnational historical

methodologies.

In 2006 Giselle Byrnes was Fulbright Visiting

Professor in New Zealand Studies at Georgetown University, Washington

DC, and she has served a term as National President of the New Zealand

Historical Association.

CONTACTS

Professor Giselle Byrnes

Faculty of Law, Education, Business and Arts

Charles Darwin University

E-mail:

Giselle.Byrnes@cdu.edu.au

FIG-IIHSM CONFERENCE AT NORFOLK ISLAND

Visit Norfolk Island and experience the historic site together with FIG

International Institution for the History of Surveying and Measurement,

who invites you to Charting and Mapping the Pacific Paradise of the

Pitcairners Conference The conferences will be held at Norfolk

Island, New Zealand, 6-10 July 2014.

|