Article of the Month -

October 2010

|

Reducing Vulnerability to Natural Disasters in the Asia

Pacific through Improved Land Administration and Management

David MITCHELL, Australia

This article in .pdf-format

(12 pages, 98 KB)

This article in .pdf-format

(12 pages, 98 KB)

1) This paper is a peer reviewed paper prepared

for the FIG Congress 2010 in Sydney, Australia, 11-16 April 2010. At the

Congress it was presented in a session about Spatial Information for

Climate Change Monitoring and Other Natural Disasters Management

and draws on the lessons from recent major disasters and existing

literature on land issues.

Handouts of this presentation as a .pdf file.

Key words: climate change, natural disasters, tenure security,

disaster resilience, vulnerability.

SUMMARY

There is evidence linking climate change with an increase in the

frequency, severity, and unpredictability of natural disasters in the

past decade. Between 1974 and 2003 there were 6,367 such destructive

natural disasters, resulting in over 2 million deaths, with 75% of these

in Asia alone (Guha-Sapir et al, 2004). Lessons from the 2004 Asian

tsunami, recent earthquakes in India and Indonesia, and tropical

cyclones in the Philippines and Samoa have highlighted the significant

land issues that can arise in the aftermath of the natural disaster.

This includes people losing access to land through resettlement, and

land grabbing causing loss of connection with pre-disaster sources of

livelihood. Since the Asian tsunami there has been extensive analysis of

the approaches taken to address these land issues after natural

disasters, and the literature contains several case studies and

comprehensive reports from international agencies providing guidelines

for addressing land issues after natural disasters.

This paper concentrates on issues in developing countries in the Asia

Pacific and draws on the lessons from recent major disasters and also

existing literature on land issues. Coastal communities are often at

greatest risk of these events and it is often the poor sections of the

community who occupy land at greatest risk. The paper also refers to the

links between community vulnerability and tenure security.

1. INTRODUCTION

There is evidence linking climate change with an increase in the

frequency, severity, and unpredictability of natural disasters in the

past decade. Between 1974 and 2003 there were 6,367 such destructive

natural disasters, resulting in over 2 million deaths (Guha-Sapir et al,

2004). The Asia Pacific region includes the volcanic ring of fire in the

Pacific and the cyclone and storm paths of East Asia. An analysis of the

data on natural disasters in EM-DAT reveals that more than 75% of the

total number of people killed by natural disasters between 1994 and 2003

were in Asia (Guha-Sapir et al, 2004). Losses causes by natural

disasters are greater in developing countries in Asia and the Pacific,

and the poor are particularly vulnerable. While the 2004 Asian tsunami

received much press, disasters such as earthquakes, tropical cyclones,

avalanches, landslides and floods are also common in many countries in

the region.

Natural disasters such as these cause damage to land and loss of

access to land often results in loss of shelter and livelihoods,

sometimes permanently. During the response to the natural disaster there

are many tensions and difficulties relating to the relocation of

affected communities, the placement of refugee camps, and measures to

increase future resilience through avoiding reconstruction on land at

risk of further hazards. Vulnerability to disasters is dependent of

several factors including the degree of exposure to sites at risk of

disaster, social factors such as the level of conflict and

discrimination, the strength of the economy, and the level of

environmental degradation. Among these vulnerability factors is the

level of tenure security for landholders and this will be discussed

throughout this paper.

One of the lessons from recent natural disasters is that the poorest

and politically weakest members of society are the most vulnerable to

the impacts of natural disasters. This was the case in the aftermath of

the 2004 Asian tsunami with poor landholders most vulnerable to being

displaced from their land. In Aceh disputes over land arose, caused by

opportunistic land grabbers, and uncertain inheritance rights where the

parents had perished (6,000 inheritance cases were filed in the first

three months). Also where building foundations were deeply buried and no

traces of land parcel boundaries existed, restoring property rights was

even more complex (BRR and the World Bank, 2005). There was also the

question of whether reconstruction should occur in hazard prone areas.

In Thailand the security of tenure was put under even more pressure in

tsunami-affected areas within tourist destinations, and areas with high

property values. Handmer et al (2007) reported on the displacement of

many local people along the Andaman coastline in Thailand following the

Asian tsunami, and the incidence of tourism land developers taking

control of these areas. They reported that local people were unable to

prove formal title over land due to lack of formal tenure or loss of

land title documents. This opened up the opportunity for land

developers. This is evidence of a breakdown in governance impacting on

the land rights of these individuals.

Work commissioned by UN-HABITAT and UN-FAO has resulted in several

case studies of the land issues following natural disasters including

earthquakes in India, the Philippines and Indonesia; the 2004 Asian

tsunami, tropical cyclones and floods in Bangladesh and the Philippines;

and mudflows and landslides in the Philippines. This work has led

towards, among other initiatives, the preparation of a set of guidelines

on addressing land issues after natural disasters (Fitzpatrick, 2008).

Whilst the nature of the land issues differs depending on the type of

natural disaster and the situation of the country, some common lessons

can be drawn from this literature.

Natural disasters often involve temporary resettlement of large

numbers of people and the choice of location should be chosen in

consultation with the community, and where possible, be within reach of

pre-disaster livelihoods. The risks are that people will be resettled in

unsuitable areas and return to affected lands too early, or that

conflict will result within the resettlement areas. Principle 2 of the

Pinheiro Principles (Inter-Agency, 2007) involves the right to housing

and property restitution for refugees and displaced persons, and states

that all displaced persons have the right to have restored to them any

housing, land and/or property of which they were arbitrarily deprived,

or to be compensated where it is factually impossible to restore as

determined by an independent, impartial tribunal. In the event of a

catastrophe this is a challenge for the central government, especially

in developing countries, as the cost of compensation may be very high.

Resettlement should not be on land where others have claims unless by

agreement with a host community, or on government land. Also,

recognition of land rights is important during resettlement and also for

subsequent restitution, otherwise people fear eviction.

Disasters usually result in high levels of loss of access to

productive land, loss of crops and livelihoods. Some people may be

forced to sell their land and others may not be able to meet their

sharecropping or lease agreements. These pressures can lead to land

conflicts. Natural disasters also have a significant impact on the

capacity of land administration systems through loss of staff, damage to

boundary markers and survey marks, damage to land records and land

offices. In most countries in the region the land administration system

is weak in any case and the impact of the disaster further weakens the

capacity of the land agencies. Soon after the 2004 Asian tsunami, the

Indonesian Land Agency (BPN) issued a decree preventing the selling of

land in an effort to stop land speculation, and while it is hard to

judge the degree of informal land transactions that may have occurred,

there were not widespread reports of land grabbing.

Existing tenure security issues and problems are highlighted after

disasters, and the recovery and reconstruction phase is an opportunity

to assess these. Disasters affect urban and rural lands and invariably a

range of tenures and forms of access rights to land. Often the landless

(labourers and sharecroppers, etc) and people with insecure tenure are

the most vulnerable to disasters. There is a need to quickly assess

previous formal, and informal land rights that existed prior to the

disaster, and these often vary in legal and social legitimacy. In some

cases long established customary rights exist without legal recognition.

Recognition of informal tenure and partial rights such as squatters, or

sharecroppers, or renters is necessary but more difficult to adjudicate.

So, a flexible approach to adjudicating and validating land tenure is

needed.

There is an urgent need for adjudication of rights, prior to

construction, to determine eligibility for assistance for rebuilding or

reconstruction. However, the sheer scale of the challenge facing those

responsible for the emergency response is often enormous. During the

emergency response and subsequent recovery a trade-off is needed between

rebuilding homes as quickly as possible, and undertaking a transparent

and community driven process. Often the land records needed to make

decisions on pre-disaster rights to land are either out of date or have

been destroyed. Also, a loss of personal records and formal government

land records complicates the adjudication process. Therefore decisions

on the adjudication of rights to land should be made in close

consultation with the community and where possible be based on

consensus.

The lessons from recent natural disasters provide an opportunity to

consider what actions communities at risk of natural disasters can take

to reduce their vulnerability to natural disasters and increase their

resilience in the event of a natural disaster. This is of particular

importance to the poorer coastal communities in the Asia and Pacific

region as the potential for rising sea levels and more frequent storm

events increases their vulnerability. Natural hazards such as tidal

surges, landslides, floods, cyclones, hurricanes and volcanic eruptions

can affect communities on a recurrent basis. The urban poor in coastal

communities are often at greatest risk of these recurrent events and it

is often the poorer sections of the community who settle in hazard prone

areas. In many cases the land they occupy is not subject to building

controls and settlements development with informal dwellings and no

legal recognition of their land tenure (Quan and Dyer, 2008).

2. LAND TENURE AND DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT

Secure land tenure provides a degree of economic security for the

landholder and, assuming appropriate governance, provides protection

against other interests. In a seminal World Bank publication on property

rights, Deininger (2003) stated that “tenure security depends on a host

of objective and subjective factors, including the clarity with which

rights and obligations are defined; the quality and validity of property

rights records and whether or not the state guarantees them; the

precision with which boundaries are demarcated; the likelihood that

rights will be violated; the ability to obtain redress by an

authoritative institution in such cases, along with the reassurance that

whatever measures the institution decides are deemed appropriate and can

be enforced effectively. Deficiencies in any of these areas, or a

mismatch between different components of the property rights system, can

seriously undermine tenure security, thereby increasing the potential

for conflict and undermining the incentives for investment and change”.

Over the last 15 years various countries in the Asia and Pacific region

have implemented land administration projects that involve the creation

and registration of land titles. The objectives of many of these land

administration projects have been to improve tenure security and access

to land, potentially resulting in more efficient agricultural production

and improved livelihoods, improved governance and equity (Mitchell et

al, 2007).

However, many countries in the Asia Pacific region do not have a

formalised land tenure system and rely on customary arrangements, and

other types of informal tenure. Whilst such arrangements might have been

suitable in traditional and historical circumstances, pressures on land

tenure due to climate change will result in an altogether different

reality. Even in countries with land titling programs, much of the

occupied land remains under state control, or lies outside the scope of

the titling project.

Land that is agriculturally marginal, or hazard-prone, tends to have

no formal land tenure in place and the occupiers have settled there

because they don’t have claim to any other land. They typically have

very poor infrastructure and limited government support. In hazard-prone

areas this presents a problem as they are at high risk of the impact of

a natural disaster and also very vulnerable to loss of access to land

and the livelihoods they derive from the land or associated water

resources. Natural hazards such as floods may only affect a community or

agricultural land every few years, but the damage can be significant.

Landholders need to find ways to live with the threat of the disaster,

respond when the disaster occurs, and to rebuild their homes and

livelihoods after the event.

Tran et al (2007) argued that the Vietnamese people are very used to

living with severe floods and this is embedded in their culture.

Accordingly they have had a large system of river and coastal dykes in

place to control flooding for centuries, and this has worked on most

occasions. However, they add that “this structural approach to flood

control is now under pressure because the conditions inducing flooding

are intensifying, both at the local and global level…For example,

population increase, rapid urbanization, high demand for natural

resource exploitation, environmental pollution, and degradation are

coupled with global threats, such as climate change”. This theme is

continued by Satterthwaite et al (2007) who argue that in addition to

government adaptive response, the urban poor demonstrate a significant

capacity to undertake measures such as building shelters and drainage

channels to protect themselves and their properties from flood risks.

This was the experience also in Aceh where Fitzpatrick and Zevenbergen

(2007) reported that “coastal communities proved remarkably resilient

after the tsunami…community-based methods and approaches proved the most

successful in fostering sustainable and largely conflict-free recovery”.

However, Quan and Dyer (2008) argued that “Such autonomous

adaptations are however constrained by insecure land tenure which

creates disincentives for people to invest scarce resources in risk

reduction. For both new and existing settlements more secure land tenure

is required so as to improve resilience to sea level rise related risks

by promoting investments in better housing and community

infrastructure”.

Analysis of recent natural disasters has provided lessons for future

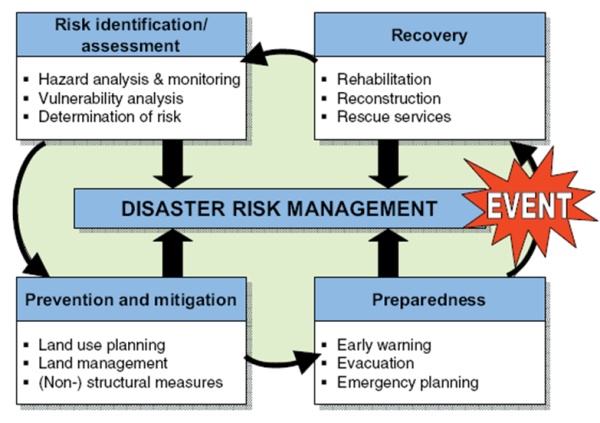

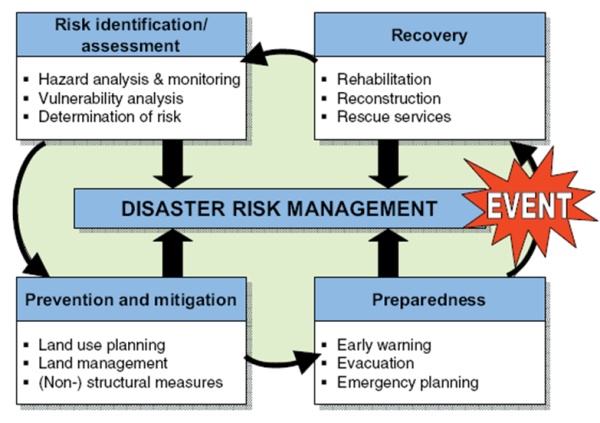

Disaster and Risk Management (DRM). Figure 1 provides an overview of the

post-disaster processes in a typical DRM framework that includes

recovery, risk assessment, prevention, mitigation and preparedness. Each

of these stages provides opportunities for improvements to land

administration and management that lay the basis for reduced

vulnerability.

Figure 1. Key Elements of Disaster Risk Management (Source: FIG

(2006))

Responses to natural disasters need to consider land issues in the

preparation for early recovery. Secure land tenure is important in

responding to natural disasters in terms of allocating assistance and

retribution in reinstating homes and livelihoods. However, if land

tenure is unclear or uncertain, post-determination will be difficult and

may exacerbate the negative impact of the weather event and undermine

community cohesion and peace-building. There is also often an inevitable

need to relocate people due to changed conditions following the natural

disaster. This was the case in Aceh following the tsunami. A sudden

tectonic plate movement in Sumatra caused the tsunami and also pushed

down the coastal shelf along much southern Aceh, especially around

Singkil (BRR and the World Bank, 2005). The result was that many areas

are now 1.5 meters lower than prior to the tsunami and much of the

previously occupied land is flooded every high tide. This inevitably led

to decisions on where people should be relocated and the likely impact

on their livelihoods.

Lessons from responses to the Asian Tsunami indicate that tenure will

be secure in natural disaster responses where there is adequate land

administration data or the land records received little damage,

landholders have documentary evidence of legal rights to land, the land

administration system is responsive and flexible, and the governance

arrangements of land administration agencies allow for fast and

transparent processes for claims to land and inheritance. The question

of whether or not to rebuild in hazard-prone areas is also significant.

In addition, proof of ownership brings the possibility of using the land

as collateral for investments in disaster recovery actions. In face of

these challenges, the strength and cohesiveness of the local community

as very significant in the protection of property rights in the event of

a natural disaster.

3. REDUCING THE VULNERABILITY OF COMMUNITIES TO LOSS OF LAND

Following the recovery phase following a disaster there are

opportunities to reflect on the land issues that have arisen and develop

risk reduction measures what will reduce the vulnerability of those at

risk. Formal recognition by government of all valid forms of existing

tenure is paramount. Disaster mitigation should therefore include an

assessment of the security of tenure in areas at risk of natural

disasters and the communication of the results to the community. In

particular, the rights of women and children and disadvantaged social

groups should be identified. This would place landholders in a stronger

position to negotiate in the event of a natural disaster.

The first part of this opportunity is improving the capacity of the

land administration to cope with future events. The developing countries

in the Asia Pacific region are quite diverse in land tenure systems and

governance arrangements, which makes it hard to generalise. However,

there are large areas of customary land in many of these countries. On

private land informal arrangements are more common than land titles. In

most of these countries there are problems with the capacity of the land

administration system that exacerbate the challenges in the event of a

natural disaster.

An improvement to the capacity of land offices in areas at highest

risk of natural disasters is important in reducing vulnerability for

those with land titles. Capacity building of land institutions is

central to improved governance as many existing institutions do

currently have the capacity to implement the DRM measures required. This

capacity building could take the form of training staff in the land

issues that arise after disasters, developing an inventory of informal

rights to land, and taking steps to protect the land records and survey

infrastructure from the impact of a natural hazard. With improved

capacity in the land administration agencies comes an opportunity for

land experts to be more involved in the improvement to tenure security.

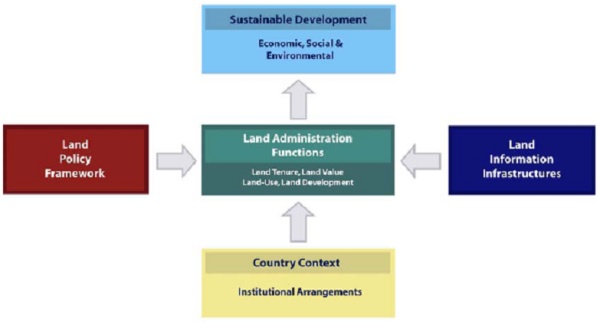

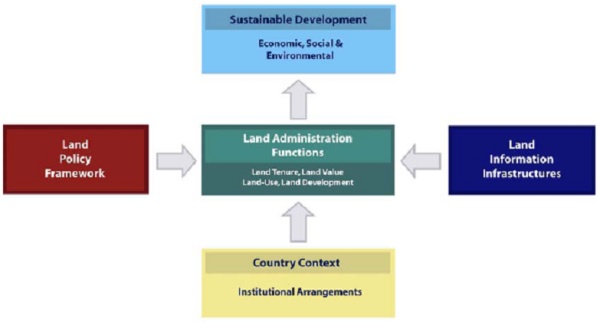

The land management paradigm outlined by Enemark (2004), describes

land management as the components of land administration as land tenure,

land valuation, and land use management, supported by a land policy

framework and land information infrastructure (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Land Management Paradigm (Source: Enemark, 2004)

The most significant long-term impact that land administration can

have on vulnerability is the improvement of tenure security for those

without legally recognised rights to land. This applies to both

privately occupied land and to collectively managed land. Brown and

Crawford (2006) presented the results of a survey of humanitarian and

development professionals, commentators and academics involved with

disaster management and mitigation. They reported that the respondents

agreed that clarity over private and communal land ownership was

critical to the effective reconstruction of disaster-affected regions.

This clarity allowed them to provide secure credit for reconstruction,

and allowed them to benefit from any compensation packages that may be

offered. However, improving tenure security is by nature a complex and

long-term process and it is widely considered that improvements to

tenure security should be incremental and progress up a ‘ladder of

rights’ (GLTN 2008, Barnes and Riverstone 2009). The development of an

updated land policy framework is the appropriate way to commence the

process of improving tenure security. Lessons from previous disasters

should be catalogued and used as a basis for the development of land

policies that consider land tenure issues in hazard-prone areas, using a

participatory and transparent process. Previous experience suggests that

the success of implementation of land policies will inevitably be depend

on a range of factors including governance, political will, and the

degree of public involvement in the development of the policies.

Closely related to improvements to tenure security is the necessity

to educate the public about their rights to land, so that they are less

likely to be taken advantage of in the event of a disaster. Part of this

responsibility lies with the land agencies to undertake community

education programs about land polices and laws and their rights within

these.

Improvements to land valuation also are important to reducing

vulnerability to inadequate compensation where loss of land occurs

following a natural disaster. Approaches to DRM can also make allowances

for compensation payments in the event of a disaster. Developing

up-to-date land valuation maps and records will provide a basis for

discussion of compensation. Information of this type places the

landholders in a stronger bargaining position with government when

compensation is discussed.

Land use management (or physical planning) also has a role to play in

reducing vulnerability. Land use master plans that consider the risk of

settlement in hazard-prone areas are important. Decisions on

resettlement should be made in consultation with land experts and in

high-risk areas the choice of potential resettlement sites in the event

of a disaster could be made in consultation with the public prior to the

occurrence of a natural hazard. In extreme cases there may be a need to

consider whether some people should be permanently resettled to areas

with less risk. However, there are many potential problems with this

approach and decisions need to be made in close consultation with the

landholders otherwise they risk loss of tenure security, loss of access

to previous livelihoods and social fragmentation. For example, after the

2004 Asian tsunami the Sri Lankan government created coastal zones of

between 100m and 300m preventing housing construction in tsunami

affected areas an effort to avoid a repeat of the devastation. This

would have resulted in the relocation of many thousands of people and

risk increasing tensions between resettled and existing communities

(Brown and Crawford, 2006). These restrictions were eventually relaxed.

The Hyogo Framework for Action (ISDR, 2005) calls for, among many

recommendations, for disaster risk assessments to be incorporated into

urban planning and management in disaster-prone settlement areas. This

is endorsed by Enemark (2009, p12) who states that “Integration of all

aspects of the disaster risk management circle…into the overall land

administration system will enable a holistic approach that should

underpin the general awareness of the need for being prepared for

natural disasters and also being able to manage actual disaster events”.

The respondents in the survey by Brown and Crawford (2006) believed that

poor land-use planning increased disaster vulnerability through delays

to reconstruction, and increased tensions between those competing for

scarce resources. In the absence of cohesive land use planning prior to

a natural disaster one of the issues that invariably comes up during

reconstruction efforts is whether humanitarian and development

organizations should take advantage of the significant severance between

people and their landholdings to implement more sustainable land

ownership systems moving forward.

In the absence of climate change recognition in land policy

spontaneous adaptations will occur. The lessons for adaptive planning

and climate change mitigation are in the consideration of the

implications of climate change on existing land tenure and land use

arrangements, the likely impact on tenure systems of mitigation

measures, and how climate change can be incorporated into land policies.

Quan and Dyer (2008) argued that:

“The progressive ingredients of urban land policies to upgrade

informal settlements, improve tenure security, increase delivery of

appropriate land through public-private collaboration, simplify and

strengthen planning arrangements, and extend popular participation

therefore all have a significant role to play by improving the

incentives and flexibility for individuals, small businesses and

communities to adapt to the risks of sea level rise”.

By bringing land administration and physical planning closer

together, and supported with disaster risk information better decisions

on land tenure and land use are possible, and the poorest will benefit.

4. CONCLUSIONS

There is growing evidence that climate change will lead to an

increase in the incidence of natural disasters. The likelihood is that

recurrent events such as tidal surges, cyclones, and floods will become

a greater problem for some communities. Unfortunately the people most

vulnerable are often the poorest section of the community, and often

live in areas with informal tenure. Security of tenure is an important

factor in the reconstruction and restitution after a natural disaster

and should therefore be considered as an element of the vulnerability of

communities to natural disasters. Improved tenure security strengthens

the negotiation powers of the poor, and can reduce the likelihood of

land grabbing, assist in reconstruction efforts and help with access to

collateral for financing reconstruction. Education of individual’s

property rights and level of tenure security is also important.

Land administration and management can reduce the vulnerability of

people to natural disasters through improved capacity to make decision

on land, the development of land policies that includes the lessons

learned from previous disasters, the development of land valuation

records in at-risk areas, and the development of sound land use master

plans that consider risk areas and resettlement options in consultation

with the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank his colleagues in the School of

Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences for their input and support.

REFERENCES

- Badan Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi (BRR) and the World Bank,

2005, Rebuilding a Better Aceh and Nias: Stocktaking of the

Reconstruction Effort - Brief for the Coordination Forum Aceh and

Nias (CFAN). For the people of Aceh and Nias, October 2005.

- Barnes, G. and G. Riverstone, 2009, Exploring Vulnerability and

Resilience in Land Tenure Systems after Hurricanes Mitch and Ivan.

Accessed 12/12/09.

www.sfrc.ufl.edu/geomatics/courses/SUR6427/Barnes-riverstone-pap.doc

- Brown, O., and Crawford, A., 2006, Addressing Land Ownership

after Natural Disasters: An Agency Survey, International Institute

for Sustainable Development (IISD), Winnipeg, Canada.

Deininger, K., 2003, Land Polices for Growth and Poverty Reduction,

A World Bank Policy Research Report, World Bank and Oxford

University Press.

- Enemark, S., 2004, Building Land Information Policies,

Proceddings of the Special Forum on Building Land Information

Policies in the Americas, Aguascalientes, mexico, 26-27 October

2004,

www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

- Enemark, S., 2009, Sustainable Land Administration

Infrastructures to support Natural Disaster Prevention and

Management, UNESC, Ninth United Nations Regional Cartographic

Conference for the Americas, New York, 10-14 August 2009.

- FIG (2006): The Contribution of the Surveying Profession to

Disaster Risk Management. FIG Publication No. 38. FIG Office,

Copenhagen, Denmark.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub38/figpub38.htm

- Fitzpatrick, D., and Zevenbergen, J., 2007, Addressing Land

Issues after Natural Disasters: A Study of the Tsunami Disaster in

Aceh, Indonesia: Draft.

- Fitzpatrick, D., 2008, Guidelines on Addressing Land Issues

after Natural Disasters: EGM Draft 21-23 April 2008, UN-HABITAT/UN

FAO/UNDP.

- Global Land Tools Network, 2008, Secure Land Rights for All.

Nairobi, UN-HABITAT.

Guha-Sapir, D., Hargitt, D., and Hoyois, G., 2004, Thirty years of

natural Disasters 1974 – 2003: The Numbers, Centre for Research on

the Epidemiology of Disasters,

http://www.unisdr.org/eng/library/Literature/8761.pdf, Accessed

22/09/2009.

- Handmer, J. And Choong, W., 2006, Disaster resilience through

local economic activity in Phuket, The Australian Journal of

Emergency Management, Vol. 21 No. 4, November 2006.

- Inter-Agency, 2007, Handbook on Housing and Property Restitution

for Refugees and Displaced Persons: Implementing the 'Pinheiro

Principles'. Turin, FAO/iDMC/OCHA/OHCHR/UN-HABITAT/UNHCR.

- ISDR, 2005, Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the

Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. World Conference

for Disaster Reduction, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan.

Mitchell, D., Clarke, M., and Baxter, J., 2008, Evaluating Land

Administration Projects in Developing Countries, Land Use Policy,

25(4) pp. 464-473.

- Quan, J., and Dyer, N., 2008, Climate Change and Land Tenure:

The implications of Climate Change for Land Tenure and Land Policy,

IIED, UN FAO Land Tenure Working Paper 2,

ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/011/aj332e/aj332e00.pdf, Accessed

03/08/2009.

- Satterthwaite D., Huq, S., Pelling M., Reid H., Lankao P.R.

(2007) Adapting to Climate Change in Urban Areas: The possibilities

and constraints in low- and middle-income nations, Human Settlements

Discussion Paper Series, IIED available at

http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/10549IIED.pdf, Accessed

21/09/2009.

- Tran, P., Marincioni, F., Shaw, R., Sarti M., and An, L., 2007,

Flood risk management in Central Viet Nam: challenges and

potentials, Natural Hazards, Volume 46, Number 1 / July, 2008.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

David Mitchell is a licensed cadastral surveyor and worked in

private practice for 12 years before joining RMIT University, where he

has been for 12 years. He is the Australian delegate to FIG Commission

7. David is an international land administration consultant and

undertakes research at RMIT University focusing on the development of

effective land policy and land administration to support tenure

security, improved access to land and pro-poor rural development.

CONTACTS

Dr. David Mitchell

School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences,

SET Portfolio, RMIT University

GPO Box 2476V

Melbourne

AUSTRALIA

Tel. + 61 3 9925 2420

Fax + 61 3 9663 2517

Email: d.mitchell@rmit.edu.au

Web site: http://www.gs.rmit.edu.au

|