Article of the Month -

february 2010

|

Land Acquisition in Developing Economies

Jude WALLACE, Australia

This article in .pdf-format (21

pages and 1.4 MB)

This article in .pdf-format (21

pages and 1.4 MB)

1) This paper is based on the keynote

presentation that Jude Wallace gave at the 7th FIG Regional Conference

in Hanoi, Vietnam, 19-22 October 2009. This invited paper addresses the

issue of land acquisition in emerging economies that will be further

explored in the FIG publication to be launched at the FIG Congress in

Sydney in April 2010.

SUMMARY

Land administration theory has developed a new, multi-disciplinary

approach to building, designing and managing land administration systems

(LAS). The articulation of the approach runs parallel to development of

land indicators to improve reliability and usefulness of international

comparisons of LAS tools, especially in response to demands for good

governance.

These developments form the background to formulation of human rights

based land acquisition standards. However, land delivery processes in

general, and the sub-set of compulsory land acquisition and resettlement

processes, in particular, are complex and cross-cutting. In developing

countries, technical issues, rather than humanitarian issues, tend to

paralyze attempts to reform of land delivery processes. Capacity

building is therefore a key component of reform of land acquisition

processes. New tools are emerging that both improve technical capacity

and assist with application of human rights based land acquisition

principles.

1. NEW LAND ADMINISTRATION APPROACH

Features of the new approach

The analysis of land

problems is assisted by a new multi-discipline approach to land

administration. This approach features:

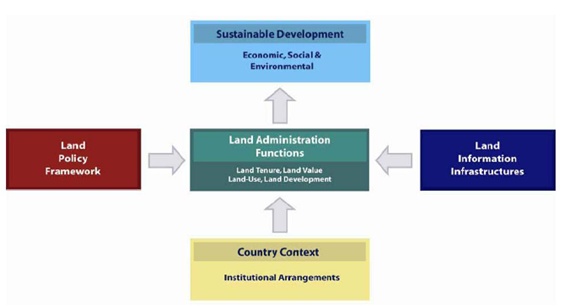

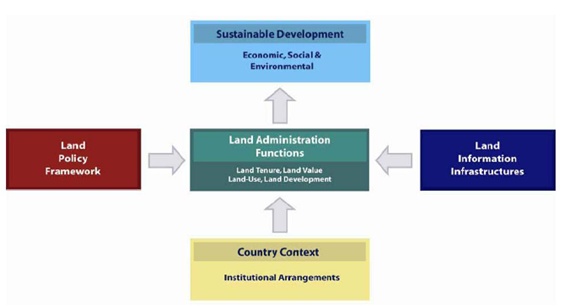

- Use of the land management paradigm to focus land administration

functions and related land policies and land information

infrastructures on sustainable development (Enemark 2004). The

country context remains the underlying starting point of any

decisions and strategies (Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. The land management paradigm

(Enemark 2004).

- A tool-box methodology that allows solutions to be developed in

the context of a country’s capacity and history. This methodology

contrasts with the out-dated, one-size-fits-all method of applying

technical Western land administration tools to countries where land

markets, if any, are informal and capacity is minimal. Figure 2

below shows the basic idea of a building a local land administration

system (LAS) using suitable tools to perform essential functions

such as registration, tenures security, cadastres, boundary

management, disputes, professional regulation and many others.

Ideally, the selection of tools is influenced by best practice

concepts, and the country’s fundamental land principles.

Figure 2. The land administration system tool

box (Enemark 2005)

- Identification of new opportunities associated with

technologies, especially spatial technologies (Williamson, Enemark,

Wallace and Rajabifard, 2010). Spatial technologies alter the range

of tools available to nations.

This multi discipline approach is described in detail by Stig Enemark

(2009). If used cleverly, the approach improves management of land,

information and, ultimately, reforms processes in all economic sectors –

government, business and civil society. The LAS needs to be designed

specifically to capture the new opportunities. National agencies,

institutions, processes and policies must operate according to a

coherent design. The design is especially essential if information is to

be used effectively. For example, the ability to utilize spatial

technologies depends on planning and building layers of land information

so that they are interactive. In mature systems, location or place

becomes a means of organising and sorting all kinds of spatial

information. The cadastre, especially the reliable, large scale land

parcel map that defines the way people actually use, think about and

organise their land, forms the fundamental layer of spatial information

in a national spatial data infrastructure (SDI). The take up of

geographic information systems (GIS) in product management, property

management, transport, emergency services and many other applications is

assisted. Once information is organised, place or location is

confidently identified according to scientifically reliable methods so

that other non-spatial information can be organised according to place

(Williamson etc). The multi-disciplinary land administration approach

ultimately facilitates spatial enablement the government, business and

society.

Given the comparatively recent arrival of the new spatial

technologies, no country has yet achieved this ideal LAS. The importance

of the new approach however cannot be neglected. Every nation is

constantly engaged in building its LAS and managing its land. The

message is to design changes that build systems that use the new

approach to deliver overall sustainable development. The new approach is

particularly relevant to developing countries with limited resources.

Financial and capacity limitations can be overcome if nations are able

to justify the financial investment in technical and human resources

needed in their LAS. Tracking of comparative national performance in

land administration functions is increasingly providing incentives for

take-up of modern systems.

Development of “land indicators”

Alongside the theoretical identification of the multi-discipline

approach to land administration, another related revolution in land

information has improved comparative methodologies. After about 1995

international agencies made concerted efforts to develop “land

indicators”, capable of being integrated with more general indicators.

The general indicators include, for example,

- corruption perceptions (Transparency International,

www.transparency.org ),

- wealth and living standards (Gini index of inequality in income

or expenditure,

http://www.photius.com/rankings/economy/distribution_of_family_income_gini_index_

2009_0.html

- environmental comparisons such as the Global Reporting

Initiatives

www.globalreporting.org

www.globalreporting.org

for measuring economic, environmental and social performance, a

collaborating centre of the UN Environment Program, UNEP,

- business comparisons (World bank, Doing Business Reports, since

2005, www.doingbusiness.org

),

These general indicators and many others now appear as routine

datasets available through the Internet.

Moving from general indicators to land indicators, Alain

Durand-Lasserve (2009) and Stig Enemark (2009) found a growing

coordination of efforts. Durand-Lasserve identified lead agencies:

- in urban areas, as the World Bank and DBS banking group

UN-HABITAT, and others.

- in rural areas, International Fund for Agricultural Development

(IFAD) and the International Land Coalition (ILC), and

- in mixed areas, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), USAID

and Inter American Alliance for Real Property Rights (IARPR,

www.landnetamericas.org/Alliance/ExecutiveSummary.asp?m=21)

Many other agencies do similar work. Land indicators, both existing

and under construction, cluster around measuring tenure security, land

access and distribution, land markets, effectiveness of land

administration systems and, newly arrived, land governance. Tony Burns

(2008) summarised the following specific land indicators available on

the Internet:

- Real Estate Transparency Index, Jones Lang Lassalle

- Access to Land Indicators, IFAD

- Doing Business, property registration, World Bank

- International Property Rights Index, de Soto Institute

- Urban Governance Index, UN-HABITAT

- Access to Common Property Index, International Land Coalition

(ILC)

- Global Corruption Barometer (land indicator in 2008)

- Forced evictions, Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE)

- Legal and Institutional Framework Index (Global Urban

Observatory Group)

Burns noted that these were limited in their ability to track changes

in time or to identify specific policy interventions. A better designed

set of indicators was needed to inform decision makers on strategic

improvements to land governance. Perhaps the culmination in these

efforts can be seen in the efforts of the World Bank and Land Equity

International to identify indicators capable of testing good governance

in land administration and to apply them in countries as diverse as

Kyrgyz Republic, Burkina Faso, Indonesia, Tanzania and Peru (the initial

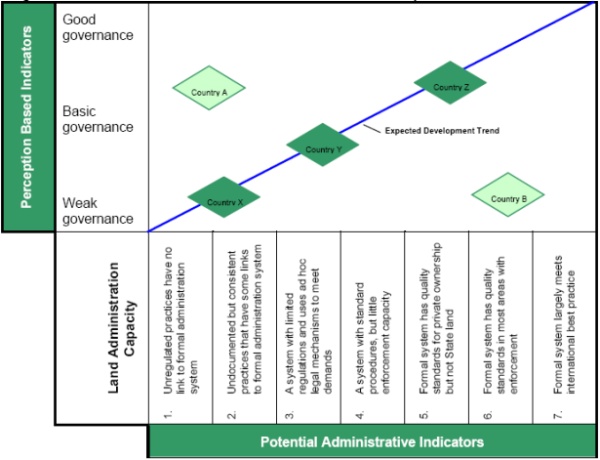

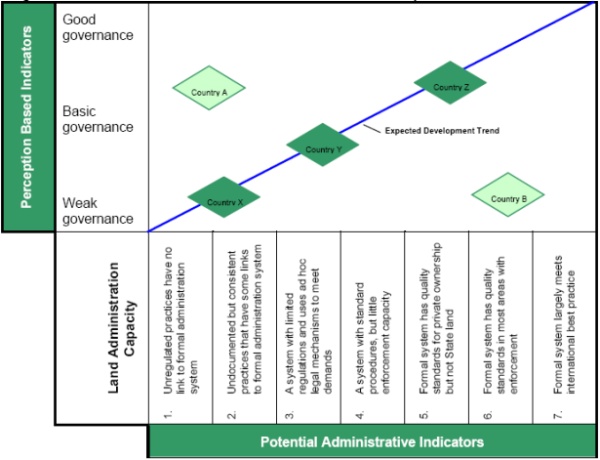

case studies). The theoretical framework of land indicators was

distilled into “applied” indicators identified in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Co-relation between Governance/Land

Administration Developments (Land Equity International Pty Ltd 2008)

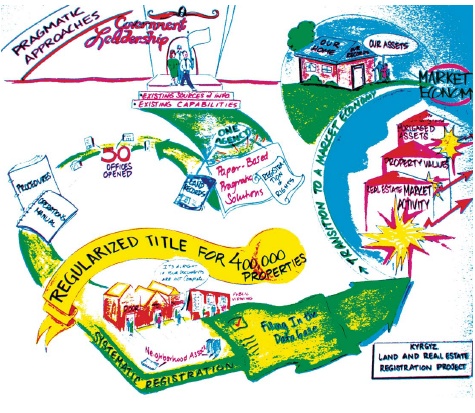

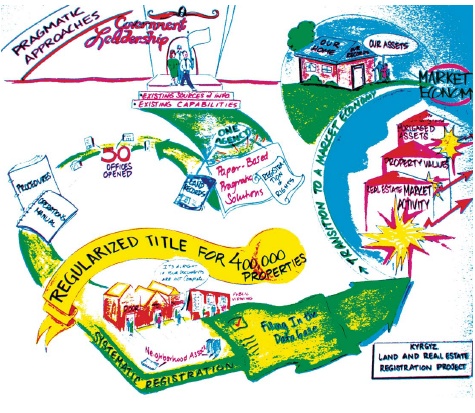

Level 7 of potential administrative indicators is achieved by few

countries, roughly those 35 or so countries who benefit from effective

national-scale LAS and free markets in land and properties, including

most members of the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and

Development (OECD). Some countries have made remarkable progress

including countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (excepting

countries with local problems such as Tajikistan, Albania and the

Ukraine), especially those driven by the desire to gain access to the

European Union.

Focus on governance in relation to land administration, and good

governance as a whole-of-government standard, changed land

administration as a discipline. In the words of Alain Derrand Leserve,

attention moved away from land administration good governance to land

governance. This mirrored the shift from technical tools of land

administration towards a broad suite of tools to implement the new land

administration theory and the land management paradigm. The over all

coherence of a LAS is then focused on national governance capacity to

deliver sustainable development using tools appropriate for the

country’s situation.

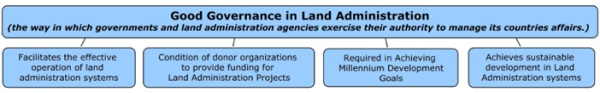

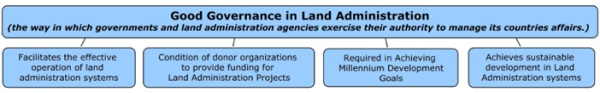

2. GOOD GOVERNANCE IN LAND ADMINISTRATION

Developing the theory

Good governance in land administration is now the primary

over-arching aim of well designed land projects. A simple summary of the

drivers to deliver good governance in land is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The drivers of good governance in

land administration, James Buchanan 2008

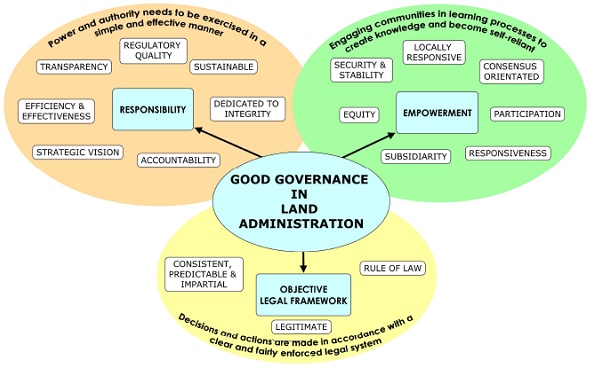

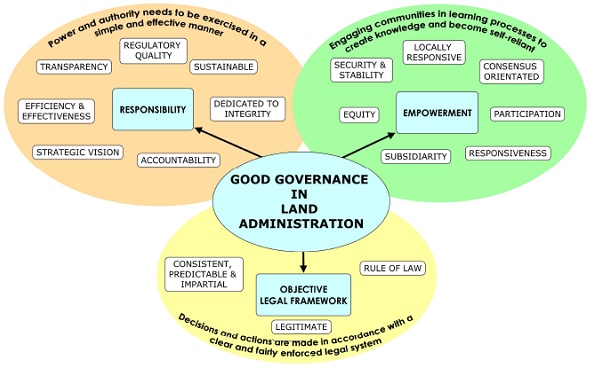

The indicators of good governance can be usefully clustered around

three outcomes: responsibility, empowerment of people and delivery of an

objective legal framework, in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Clustered indicators of good

governance in land administration, James Buchanan 2008

Good governance literature grew substantially after 2005. Principal

documents in this trend include the FAO publication on Good

Governance in Land Tenure and Administration (2007), and the World

Bank comparative study on Governance in Land Administration

initiated in 2007 and continuing. Recent additions to the library

include the FAO Land Tenure Working Papers, especially three of 2009:

- #8. Voluntary Guidelines for Responsible Governance in Tenure

of Land and Other Resources: From Civil Society Perspectives,

Jan 09

- #9. Issues from an International Institutional Perspective,

May 09, and

- #10. Discussion paper “Towards Voluntary Guidelines on

Responsible Governance

(

www.fao.org/nr/tenure/infores/lttpapers/en/ ) May 09.

These three recent papers responded to substantial copious studies

and research. Paper #9 involved distillation of another 56 international

documents to derive 14 basic principles in land tenure and natural

resources (Land Tenure Working Paper #9, 2009 page 1).

Communicating the theory

Among the 200 (plus or minus) jurisdictions of the world charged with

national level land administration, only about 30-35 countries achieve

national good governance standards most of the time. For the other 170

(plus or minus) jurisdictions, upgrading of their LAS remains a

challenge. Assistance is provided to decision-makers by publications

especially designed to explain problems and possible solutions in

understandable ways. Examples include FAO’s Good Governance in Land

Administration, Principles and Good Practices (2009a) Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. Easily understood and accessible explanations of good

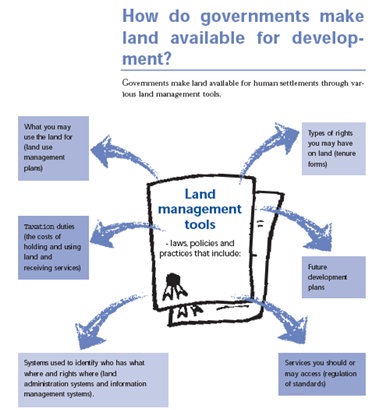

governance in land (FAO 2009d, page 20)

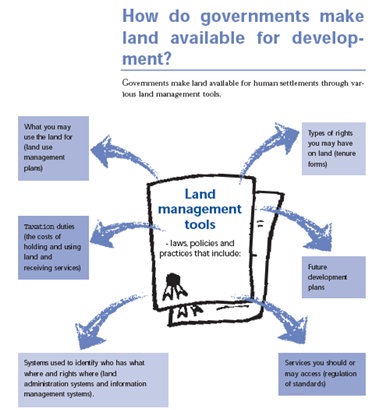

In the context of land delivery and service upgrading, UN-HABITAT

produced a simple and accessible version of their detailed Handbook on

Best Practices, Security of Tenure and Access to Land, (2004a) showing

how to make land available for development (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Accessible land management tools.

UN-HABITAT 2004b

These publications, and many others of similar type, aim to assist

decision-makers in their tasks of managing land and building sustainable

LAS. They are now an essential part of knowledge transfer that underpins

good governance capacity building. They form the background to

consideration of how a nation might handle the essential task of

delivering land to its people.

3. LAND DELIVERY

The scale of demands

Every process in land administration is, of course, important and

should be tested both against the new land administration system theory,

and the evolving good governance standards. However, land delivery

processes, and especially the sub-set of processes related to compulsory

land acquisition and resettlement, are probably the most complex,

under-examined and prone to uncoordinated responses. Hence land delivery

in developing countries provides a context in which the established

processes almost always fail when tested against emerging land

governance standards and modern land administration approaches.

In many countries, land delivery is at crisis levels. The processes

often involve geo-politics, foreign investment and development aid

interests. In most countries, formal management of land markets is

partial, driving many market activities towards informalism and ad hoc

approaches. Land delivery problems are shared by many developing

countries because their processes of land delivery and urbanisation are

fundamentally disorganized.

Lack of capacity is exacerbated by increasing demands for land and

spontaneous conversion of existing land uses. Agribusinesses, tourism

and industrial facilities and promotion of agrofuels require millions of

hectares and have devastating impact on human settlements and forests.

Increasing conversion of agricultural land for residential, industrial,

and other international investment projects is a major issue especially

for many sub-Saharan African countries, and Asia and Pacific Region

countries, especially Viet Nam and Indonesia. Simultaneously, the formal

delivery on a mass scale of small parcels for poor housing and work

places remains beyond the capacity of most governments despite massive

movement of people from rural to urban areas.

LAS delivery tools in theory

Amid this complex range of pressures, land administration theory

needs to identify a series of tools for land delivery consistent with

good government standards. Standard tools that deliver land for private

and public purposes fall into two broad categories: market acquisition

systems and human rights based acquisition systems.

Market acquisition systems

In developing countries use of formal land markets as a land delivery

mechanism fails to meet the tests of capacity. Four common problems are

well documented.

- The ability to define a “market price” is often problematic. The

most common cause of price tension is setting the value of land

destined for take-over on the basis of existing land uses,

principally farming or slum housing, and not on the basis of post

development uses, often lucrative industrial and residential

estates. Original owners and occupiers who are moved often regard

acceleration of land values as undeserved “windfalls” for the

developers.

- The secondary problem with pricing is reliance on government set

values, rather than transparent values set by land trading in an

open market recorded in formal systems.

- The property base essential for a functioning the market system

is usually inadequate: land rights claimed by owners and occupants

are unregistered or even undocumented. The targeted land is often

held in insecure arrangements, social tenures (Wallace 2009 ) and

informal systems. Price mechanisms in these cases remain flawed,

even with willing sellers.

- Lack of participation and cooperation among the occupiers and

owners in their removal from their businesses and homes makes the

trauma of physical dispossession (whether forced or not) their most

indelible memory of the process.

Human rights based acquisition systems

A human rights model of compulsory land acquisition is still under

construction. In broad terms the model seeks to solve the problems that

arise when countries with predominantly informal land markets try to use

market based solutions. The model adds additional components to land

delivery processes designed to empower land occupiers and owners. In

broad terms, these components demand land takers:

- Acknowledge entitlement of all displaced persons, including

persons with formal legal rights, persons whose claims to land are

potentially recognizable under national law, and persons who have

neither formal legal rights or land claims recognized or even

recognizable under law, such as squatters and encroachers.

- Ensure that all displaced persons are eligible for

resettlement assistance and compensation for loss of non-land and

land assets, including those without legal titles to land or any

recognizable legal rights to land. Loss of employment, not just loss

of land to occupy and use, should be compensated.

- Calculate the rate of compensation at full replacement cost.

- Provide relocation assistance for physically displaced persons,

including a livelihood assistance or income rehabilitation program

for economically displaced persons at full replacement cost.

- Provide meaningful socialization and consultation with affected

persons and other related parties about the project and its impact

on communities in the early project preparation stage and at other

crucial stages.

Most of the large international institutions apply some or all of

these standards for land acquisition or compulsory purchase designed to

both respect the rights of existing land users and owners and to deliver

secure tenure to developers, especially for public projects and projects

funded by development aid. As a general observation, even if the initial

costs of the land and the compensation constitute a high percentage of

the cost of the overall development, the budget will be justifiable

especially if land disputes are minimized and secure tenure is delivered

to the new owners.

3 BUILDING THE HUMAN RIGHTS MODEL OF COMPULSORY ACQUISITION

STANDARDS

Displaced persons protection

Parallel with the international efforts to develop good governance

indicators in land administration, professional groups, institutions and

development aid specialists are articulating appropriate indicators of

land acquisition through compulsory procedures. To complicate matters,

many acquisitions involve conquest, war and revolution. Thus a starting

point involves looking at standards of treatment of displaced persons

organised through the international efforts at resettlement of refugees,

the world’s largest groups of displaced persons, especially the refugee

displacement principles. These Pinheiro Principles, the UN Principles

on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons,

from Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE undated) are the

starting point in thinking about the human consequences of displacement.

Displacement consequences are experienced regardless of whether

interference is generated by international, intranational, or

non-national land taking activities. In terms of designing land

administration systems, nation states therefore need to anticipate the

social and human consequences of displacement by small and large scale

projects. The land acquisition processes that are institutionalized must

minimise civil unrest and disputation. The initial cost is, of course,

high. The value of these processes are however long term, especially in

their contribution to civil peace and elimination of land disputes.

Protection of people affected by land projects

International development aid agencies are also engaged in setting

standards for a human rights based model. Multilateral financial

institutions have institutionalized pro-poor and humane processes for

land delivery. The Asian Development Bank, for example, carefully

articulated and updated safeguard policy statements for compulsory take

over in 2009, especially applicable in Asia and the Pacific where 70% of

the world’s 150 million Indigenous People reside (ADB Safeguard Policy

Statements 2009, page 2). Other major development banks, including the

World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (whose standards are

adopted by 60 commercial banking institutions), the European Bank for

Reconstruction and Development, and the Inter-American Development Bank

(ADB 2009, page 2), all have standards aimed at protecting people whose

land or life styles are targeted for take-over which must be applied in

project development.

An attempt to organise the multitude of international standards was

undertaken in a Seminar on Compulsory Purchase and Compensation in

Land Acquisition and Takings, 2007, September 6-8, Helsinki, Finland

by a large number of interested parties, including FIG Commission 9,

Baltic Valuation Conference, FAO, World Bank, and others. The seminar

aimed to -

- Identify the legal structures and practices in compulsory

purchase and compensation in different countries.

- Determine if compensation laws, valuation methods and processes

will lead to full and just compensation and identify possible

shortcomings.

- Find possible and effective solutions to problems especially

appropriate for developing countries suffering severe capacity

limitations. Identify what are the best practices and what

principles should be taken into consideration or should be avoided,

within existing competencies.

- Identify future research directions.

http://www.tkk.fi/Yksikot/Kiinteisto/FIG/index.htm

FIG Working Group 9.1, the Global Land Tools Network (GLTN), and

others are working on guidelines for compulsory purchase and

compensation, to be finalized and announced at the FIG Congress in

Sydney in 2010. The process of development of these guidelines is open

and democratic, seeking participation from as wide a group as possible

through a questionnaire process run through FIG and GLTN -

http://www.fig.net/commission9/ and returnable on 20 August 2009.

The scope of the questionnaire was broad, reflecting the scope of issues

that are opened up when land development is proposed. The questions are

framed to inspire a well thought out human rights based acquisition

process that is compatible with the market based processes insofar as

these are available. These guidelines aim to deliver long term civil

peace derived from participation of land owners and users in the

processes of taking and redeveloping their land, delivery of security of

tenure and freedom from land claims for new users, and dispute

minimization.

These and other initiatives are refinements of the general good

governance framework for land administration, especially for land and

resource tenures (Civil Society Report, FAO 2009). One key observation

however is drawn from experiences of countries in South East Asia in

particular and developing countries in general. These emerging standards

of pro poor and humane land acquisition suffer in implementation because

projects in developing typically encounter technical problems because

they lack ability to formally manage delivery of land, both in general

and for specific projects.

Getting humane land acquisition theory to work in practice

Compulsory land purchase is part of the larger question is land

delivery itself – most developing countries experience difficulties in

delivering land for any purpose through formal systems and hence tend to

rely on ad hoc responses. Common characteristics of these responses

include –

- “Deal tenures” specific to a project (usually for large tourist

or industrial projects) which are negotiated by the parties in

informal and, sometimes, concealed arrangements.

- Ad hoc and informal land delivery for the poor through

squatting, encroaching or participating in informal markets (their

most common means of acquiring land). These delivery systems leave

the poor with little or no proof of their association with land.

- Under-funding of delivery of land for poor housing and

workplaces (contrast Viet Nam where provision of pro poor housing is

relatively successful and avoids large scale residential slums) .

- Mass land acquisition and clearance for urban renewal: China

provides the best known examples. Urban renewal on mass scale

usually does not comply with best practice in land acquisition

because activities involve forced evictions and demolition of

historical and personal spaces.

- Forced land use changes: Indonesia and its neighbours experience

massive conversion of natural forest to plantation or wasteland

through processes that disregard Indigenous Peoples and traditional

occupiers.

- Forced evictions from land needed for private purposes, often

with valuation for compensation set at government assessed values

according to existing land use, leaving the developer or the state

to reap the windfall delivered from change of purpose (eg conversion

of slums to middle class housing).

- Inability to deliver land for public purposes. Initial attempts

at formalising systems frequently lead to paralysis in land

delivery: Indonesia experiences many examples of stalled projects

including major infrastructure projects like toll roads and airport

facilities.

- Mass removal of homes and workspaces for “public purposes”. This

can occur despite legitimate public interest and planning

motivations, eg Hanoi’s removal of houses along the Red River banks

to prevent erosion, and removal of street stalls to create a neater

city. The overall public benefit rarely convinces those who are

moved that their compensation is fair.

5. WHY LAND ACQUISITION IS DIFFICULT

Land delivery theory

Land administration systems must be able to manage delivery land for

essential developments, private infrastructure and change of land uses

in response to human, social and economic demands.

Countries often lack a theoretical basis to form their fundamental

policy of land taking. Eminent domain (a term familiar in European

countries) is the government ability to take land particularly in civil

law countries. In developing countries with civil law history,

government capacity can be an initial problem. Civil law countries which

give strong constitutional protection of land ownership restrict

opportunities for compulsory acquisition, sometimes with fatal results

for public projects.

For countries sharing an English, common law heritage, compulsory

acquisition is the familiar method. The overarching ability of

government to take private land for public purposes is unquestioned. The

opportunity of the government to take land is regulated by legislative

processes and standards of acquisition. These standards apply to private

land. Market systems support the owners’ expectations to be compensated

at a value equivalent to commercial or market value estimated by a

valuation of a professional. Where a free and formally organised land

market operates, governments are able to offer market based methods of

land delivery that are not available in countries with informal markets.

Countries with formalized processes experience minimal human and social

consequences for land delivery, and use systems of compulsory taking

manage the free rider problems associated with opportunities to gouge

developers otherwise available to “last owners to agree” to an

acquisition.

In developing countries clearly articulated theoretical foundations

are typically not available, especially if the two basic approaches of

civil and common law used in market based countries are inevitably

associated with pre-independence colonial experiences. The starting

point in these countries lies in framing a clear constitutional

framework and laws that establishes the basis for taking land in

situations of unwilling sellers and occupiers, ideally incorporating the

human rights standards for resettlement. Often laws along these lines

already exist. The problems lie in technical abilities to deliver land.

Land delivery processes are cross-cutting

Even from a narrow land administration perspective, land acquisition

forms the operative intersection of processes that manage land markets,

administer land tenures and implement land use planning. Land

acquisition is therefore a complex cross-cutting issue – an issue which

is approached in each country, indeed in each local jurisdiction,

according to processes drawn from a variety of land administration

functions. In modern land administration theory, the functions of land

administration are land tenure, land use, land planning and land

development which, if the land management paradigm (the method of

understanding how the multiple processes work) is applied, are designed

to deliver sustainable development (Enemark 2009). All four functions

are involved in land delivery. In countries where all processes are

formally organised, land development involves exhaustive and extensive

consultation processes related to planning and zoning, and highly

professionalized services from government and private sector

professionals at every stage. The processes tend to be more transparent

and susceptible to public scrutiny than secret.

Developing countries lack the capacity to build equivalent processes

and often rely on NGOs for consultation expertise. Their major

incapacities however are in technical areas. Creation of land parcels

(parcellation) is a major stumbling block. Even a very simple project

involves the formal identification of land for development purposes, and

the subsequent conversion of raw land or rearrangement of formed parcels

into the development parcels. Whether market based or human rights

models of land delivery are used, technical services and administrative

capacity must be developed.

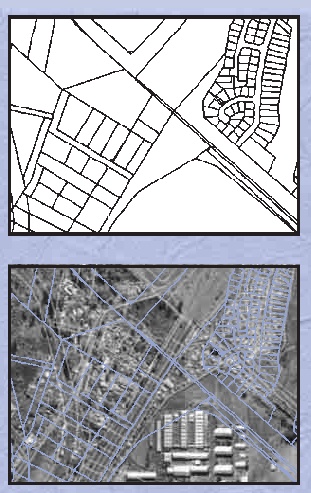

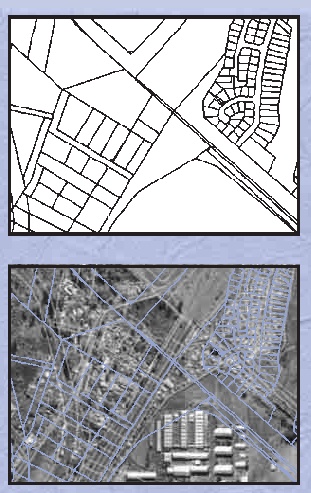

Land parcellation

Most land administration systems in developing countries lack

capacity reorganize land parcels. Parcellation includes establishment of

the boundaries of the development area, coherent arrangements with

neighboring parcels, identification of the tenure of the developer, and

the provision of facilities, including roads, public transport,

drainage, electricity, cable services, sewerage, water and so on, at the

basic minimum. These processes of subdivision and consolidation of land

are often imperfect, even with the aid of commercial funds and

professional project advice. In South East Asian cities, for example

Hanoi in Figure 7, existing parcels are frequently small scale with

narrow frontages, making reconfiguration of land for modern developments

difficult.

Figure 8. Small scale parcels in South East

Asian cities make consolidation difficult.

The divergence between existing land uses and formal parcels is often

profound (Figure 8) and compounds reconstruction and compensation

issues. Discrimination between legal and illegal land development

distributes compensation unfairly, and leads to operative paralysis in

those developing countries where “legalised” processes for land use

planning, development and tenure regulation are not available or poorly

implemented. As Figure 8 shows, determination of “ownership” of land

among urban dwellers is often not precise even with a boundary system.

Figure 9. Lack of consistency between formal

and informal arrangements. (UN-HABITAT 2004b, page 5.)

Building land delivery competencies

Within this array of complex issues, three “break through” tools can

improve land delivery processes. These are generally within the

competence of most governments. While they are independent of a

country’s ability to reach over-all compliance with good governance

indicators and land governance indicators, they are consistent. These

tools are not new and are supported by their own body of research and

experience. They are: a quick and effective land information system, a

government level tool; a strong and systematically enforced

anti-eviction law, an empowerment tool; and guidelines for management of

land grabbing, a win-win tool for foreign investors and host

governments.

Land information system – government level initiative

In the vacuum of professional surveying capacity, most developing

countries increasingly rely on land information systems (LIS) moving

into cadastral surveying as resources become available. A geographic

information system (GIS) based LIS is one of the emerging new tools

available through new spatial technologies. A systematic tool that

relates GIS, remote sensing and field surveying is described by

UN-HABITAT (2008). The tool produces a comprehensive but quick and

inexpensive information system to service especially land use planning

and property taxation. The results do not replace, and indeed cannot

replace, cadastral surveying that gives precise parcel mapping,

scientific coordination of legal boundaries with plan information, and

land use identification. A GIS based LIS offers obvious advantages for

managing people movement, consultation, and planning associated with

land delivery and especially compulsory acquisition.

Anti eviction strategies – grass roots empowerment

Countries with inadequate land administration systems and informal

markets almost inevitably use forced evictions in land delivery

processes. Many evictions, including those based on national legal

enforcement orders, ignore the international and constitutional

legislation which guarantees the right to housing and other human rights

(UN-HABITAT Advisory Group on Forced Evictions, 2007; UN Basic

Principles and Guidelines on Development-Based Evictions and

Displacement, 2007). These follow the definition of minimum security of

tenure as the rights of individuals and groups to effective protection

by the state against forced evictions (Expert Group Meeting on Urban

Indicators, 2002). Strategic impact of flexible legal formulae, like

anti-eviction laws, were further explained by Augustinus and Benschop

(2007).

In land acquisition processes these anti-eviction laws empower local

people to claim a role in negotiations related to a development,

especially if the laws provide a clear underlying opportunity for them

to complain to courts if they are ignored. The strategy is therefore

focused on capacity building at grass-roots level rather than at

government administrative levels. Good governance indicators are

therefore tested in the general courts system where they are demanded as

part of national ability to use a rule of law.

Management of hard cases of land grabbing – an initiative for

developers

Land grabbing is a common and negative aspect of land delivery. It

foments long lasting tensions and undermines civil peace. Criticism of

governments of developing countries for their failures to meet

international standards for management of land grabbing is unhelpful.

Governments need help and support in order to establish formal capacity

to manage their land delivery systems, for instance along the lines of

the recommendations for a code (von Braun and Meizen-Dick 2009). This

initiative involves strategic engagement of foreign investors and their

host countries in adopting a self imposed code of conduct for investment

in agricultural land. The code assists target countries to strengthen

their policy environment and implementation capacities by combining

their efforts with those of investors. The range of terms and conditions

in the suggested code delivers win-win solutions for all. The issues

covered are much wider than mere land administration standards, and

include implementation of good governance standards (transparency) and

human rights based standards to protect local people while delivering

essential development opportunities.

6. BUILDING THE FUTURE

The new approaches in land administration encourage civil society,

developers and governments to use new tools in land delivery processes.

The broadening of land administration theory into multi-disciplinary

competence is both welcome and essential. The addition of non-technical

goals in building sustainable systems is compatible with articulation of

standards and guidelines on land acquisition.

No developing country is in a position to apply best practice methods

throughout its entire suite of land administration processes. However,

the lessons from land administration and good governance theories are

capable of informing change strategies in most countries. Indeed, many

of the less developed nations are in a better position to adapt their

systems to modern standards than are economically successful nations

where legacy systems and technologies inhibit substantial change.

Land development is a constant in all nations and the management

tools selected by a country need to be developed in the context of their

capacity to contribute to overall good governance and sustainability.

Compulsory land acquisition, whether for development aid projects or

private projects, needs tools that work at the country level. Unless

appropriate tools are selected, land acquisition planning associated

with development aid and project financing will concentrate on

identifying standards for the social processes associated with movement

of people away from the development site and into replacement sites.

This focus misses the point that most countries need to build capacity

to undertake essential scalable and technical land delivery processes.

Other tools have unforeseen consequences. A legal framework is always

recommended; however, legalism and formalism can paralyze land delivery,

even for essential public infrastructure projects, a problem now evident

in Indonesia.

From the perspective of capacity building in land administration

efforts to improve land delivery processes must improve formal and

technical capacity to use formal systems to manage the creation of

parcels. Long term improvements that will assist removal of residents

and occupiers and their resettlement in permanent homes and alternative

work opportunities require transparent processes, formal systems that

give parcel identification, resilient boundaries and a large scale base

map built by using modern spatial technology to record coordinates. Each

of these adds capacity in the national LAS.

REFERENCES

- Asian Development Bank, 2009, Policy Paper, Safeguard Policy

Statement, Manila

- Augustinus, Clarissa and Majolein Benschop, 2007, Security of

Tenure - Best Practices, UN-Habitat, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Burns, Anthony 2008, Good Governance in Land Administration,

presentation to Land Administration Workshop: Knowledge Sharing for

the Future, 14 August 2008, Canberra, Australia,

http://www.landequity.com.au/documents/TonyBurns-GoodGovernanceinLandAdministration-14August2008.pdf

- COHRE Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) 2006

Pinheiro Principles,

http://www.cohre.org/store/attachments/Pinheiro%20Principles.pdf

- Durand-Lasserve, Alain, 2009, Land Governance for Rapid

Urbanisation, Presentation Land Governance For Rapid Urbanisation,

Land Policies and MGDs, In Response to Newly Emerging Challenges,

9-10 March Washington DC, World Bank and FIG.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTIE/Resources/A_DurandLasserve.ppt#258

- Enemark, Stig 2004, Building Land Information Policies.

Proceedings of Special forum on Building Land Information Policies

in the Americas. Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26-27 October 2004.

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

- Enemark, Stig, 2005, unpublished paper on author’s collection.

- Enemark, Stig, 2009, Spatial Enablement and the Response to

Climate Change and Millennium Development Goals, UN Regional

Cartographic Conference for Asia Pacific, 26-30 October 2009,

Bangkok.

- Enemark, Stig, 2009a, Facing the Global Agenda – Focus on Land

Governance, FIG Working Week, Eilat, Israel, 3-8 May 2009, and FIG

Article of the Month, July 2009

- FAO, 2007, Good Governance in Land Tenure and Administration.

Land Tenure Studies #9. Rome

- FAO Land Tenure Working papers

#8. Voluntary Guidelines for

Responsible Governance in Tenure of Land and Other Resources: From

Civil Society Perspectives, Jan 09

#9. Issues from an

International Institutional Perspective, May 09, and

#10. Discussion paper “Towards Voluntary Guidelines on

Responsible Governance May 09.

(

http://www.fao.org/nr/tenure/infores/lttpapers/en/ )

- FAO, 2009a, Good Goverment in Land Administration: Principles

and Good Practices, Wael Sakout, Babette Wehrmann and Mika Pettri

Torhonen, http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/i0830e/i0830e00.htm

- FIG, Working Group 9, Good Practices for Compulsory Purchase,

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2009/ppt/ts07e/ts07e_viitanen_ppt.pdf

- Land Equity International Pty Ltd, Draft Conceptual Report on

Good Governance in Land Administration, Page 20. Land Equity

International, Wollongong, Australia, circulated for comment and not

citation, The reference here aims to encourage readers to access the

Draft Report and forward comments to Land Equity

http://www.landequity.com.au/publications/Land%20Governance%20-%20text%20for%20conceptual%20framework%20260508.pdf

- Julian Quan, 2007, Towards a Harmonised Set of Land Indicators,

UNECA, Addis Ababa, 3 May 2007.

http://www.uneca.org/eca_programmes/sdd/documents/land-policy/Quan%20land%20indicators%20UNECA.ppt

- UN-HABITAT, 2002, Expert Group Meeting on Urban Indicators,

Nairobi, Kenya.

- UN-HABITAT, 2004a, Handbook on Best Practices, Security of

Tenure and Access to Land, Nairobi.

- UN-HABITAT, 2004b, Pro-Poor Land Management, Integrating Slums

into City Planning Approaches, Nairobi.

- UN-HABITAT, 2008, Systematic land Information and Management:

Technical Manual for Establishing and Implementation of a Municipal

Geographic Information System, Nairobi, Kenya

- von Braun, Joachim and Ruth Meizen-Dick, “Land Grabbing” by

Foreign Investors in Developing Countries: Risks and Opportunities,

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Policy Brief

13, April 2009.

http://www.landcoalition.org/pdf/ifpri_land_grabbing_apr_09.pdf

- Wallace Jude, 2009, Managing Social Tenures, Comparative

Perspectives on Communal Land and Individual Ownership: Sustainable

Futures, Routledge, London, in press.

- Williamson, Ian, Stig Enemark, Jude Wallace, Abbas Rajabifard,

2010, Land Administration Systems for Sustainable Development. ESRI

Press, San Diego. In press.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Jude Wallace is a lawyer who specialises in land policy and land

administration systems. She has worked in academia, the legal profession

and government. Previous positions include Deputy Chairperson of the Law

Reform Commission of Victoria and the Estate Agents Board.

She focuses on developing:

- appropriate legal and institutional frameworks for land

administration in tenure and titling, land transaction processes,

land markets, planning, securities and finance, professional

regulation, subdivision and development, and resource management

- integrated advice and reform strategies.

Her recent work is principally in Australia, Indonesia, Vietnam,

Iran, United Arab Emirates and East Timor. She is currently working on

an Asia Development Bank project with on implementing the Basic Agrarian

Law, Undang Undang Pokok Agraria.

CONTACTS

Ms Jude Wallace

Geomatics

The University of Melbourne

Parkville

AUSTRALIA

Tel. +61 3 8344 4431

Fax + 61 3 9347 2916

Email: j.wallace@unimelb.edu .au

Web site: http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/people/jwallace.html

|