Article of the Month -

December 2008

|

Effective and Transparent Management of

Public Land

Experiences, Guiding Principles and Tools for Implementation

Mr. Willi ZIMMERMANN, Germany

This article in .pdf-format

(17 pages and 226 kB)

This article in .pdf-format

(17 pages and 226 kB)

1) This paper is an updated version

of the paper that has been presented at the FIG/FAO/CNG International

Seminar on State and Public Land Management in Verona, Italy, 9-10

September 2008.

Key words: Land governance, public land management,

acquisition, management and disposal of state land

SUMMARY

Public land management is a critical factor for ensuring good

governance in the land administration of a country. There are common

factors involved in poor public land management. There is typically

ambiguity in authoritative roles and responsibilities, a lack of

accountability or methodology in the systems of allocation,

appropriation, disposal or use of public land, and a lack of information

on state assets. Weak governance in this area has direct and indirect

implications for citizens, and broader effects on economic development,

political legitimacy, peace and security and development cooperation.

There are a number of elements that can be applied to a strategy for

developing good governance in this area. These elements are applicable

to any country situation or stage of development. While the following

strategies have good intentions, reform is difficult as key stakeholders

in the equation often have vested interest in keeping the status quo.

Therefore, these suggestions are best applied in parallel within a

whole-of-government “good governance” strategy.

Some overarching strategies are important for setting a framework for

legitimate and accountable public land management practices.

- Developing a public land policy to provide fundamental

direction. A high-level oversight body should be involved in setting

this policy that states land policy goals and a framework of

principles for land management.

- Two keys areas of that should be addressed in a public land

policy are land classification and fiscal management. These are

primary loopholes used to conduct dishonest activities.

- Legislation should complement a policy document detailing

responsibilities and systems of management, including clear transfer

and regularization processes. It must also state enforcement

measures and ramifications.

- To improve accountability, transparency and ambiguities in state

land assets and associated activities there should be an inventory

of public land. This may eventually be linked to the registry;

however an initial inventory is a starting point.

- Institutional mandates of public land institutions should be

clear, comprehensive, and non-overlapping

- Accessible mechanisms and information to appeal government

actions related to compulsory acquisition and compensation are

essential for ensuring the rights of citizens are adhered to.

Good governance in the management of public land links back to the

governance principles of legitimacy, accountability, fairness and

participation. Reforming the management of public land must contribute

to a basic set of development principles, namely reduction of severe

poverty, achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, progress in

good governance and transparent fiscal management of the public sector.

1. MAJOR ISSUES

The story about public land is a story of power relations, the

relationship between state and civil society and experiences – both good

and bad – during periods of nationalization, colonization, restitution

or privatization during political transition. There is a clear need for,

and interest in, sharing experiences about ongoing work on reforming the

public land sector around the world.

Many developed countries, post-transition countries and developing

countries have embarked on a thorough re-evaluation of the role of

government in their societies. General principles for “good” asset

management have been established that governments need to adopt to

strengthen their public property management systems and enhance their

efficiency and transparency. There is also a trend towards public-sector

reform and delegation of decision-making over public land assets to

local authorities.

Public land is land which is owned by the nation or state. Land

rights (such as freehold, leasehold, use rights or other forms available

in the country) are issued by the government. The state’s mandate may as

well be delegated and transferred to local authorities. Public land

accounts for a large portion of public wealth of both developed and

developing countries. There is one common uncertainty when discussing

public land.

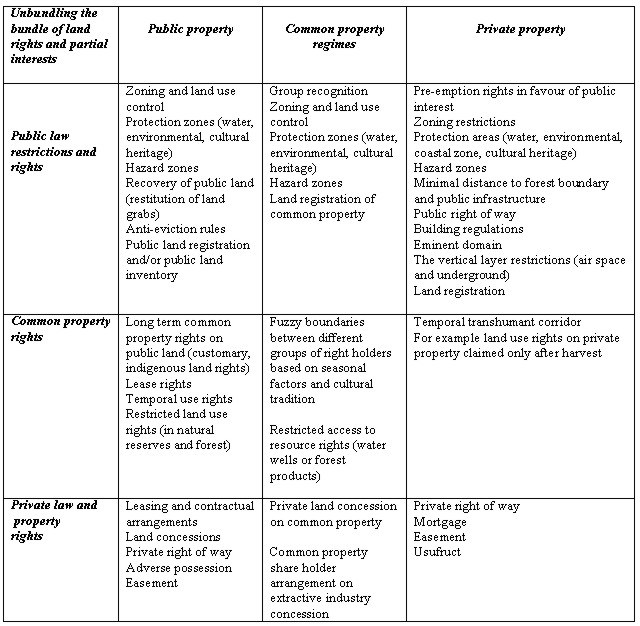

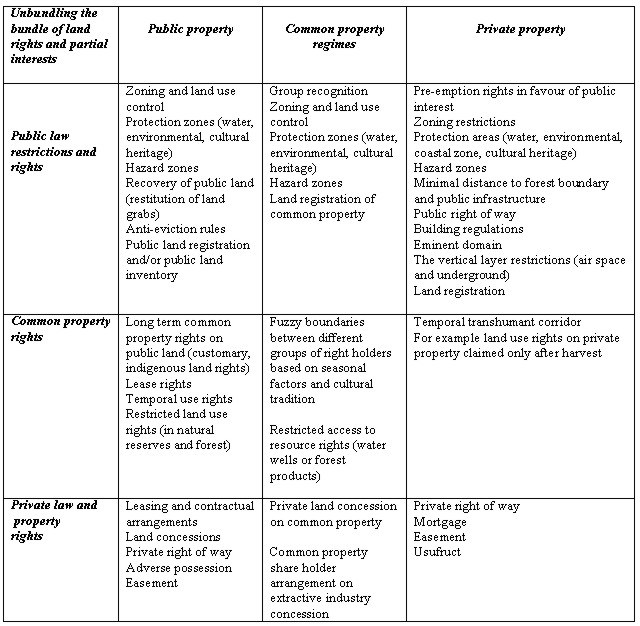

The property category PUBLIC LAND is neither rigid nor exclusive.

Generally there are bundle of rights and partial interests related to

public land as well as dynamic relationships between public land, common

property, private land and public law restrictions. Before discussing

public land matters in more detail we need to better understand this

relationships and overlap between land categories.

Table 1: The relationship between property categories.

(unfinished table for discussion)

Public property assets are often mismanaged, and nearly all countries

underutilize these resources. The power to allocate public land is of

great economic and political importance in most countries, and it is a

common focus of corrupt practices. Public land is often treated as a

“free good”, whereas “good” land in terms of location, use and service

delivery is in fact scarce and valuable. Public land management is quite

often flawed and contentious because it is dominated by a top-down

process that encourages favours to special interests and promotes

polarization to obtain such favours. As a consequence, public land

rights are often transferred through rule of power processes (Box 1) and

not a transparent market mechanism.

In many countries, the state itself is the primary threat to secure

land tenure arrangements related to public land.

Violation of good governance principles is most common in managing

state property assets. Some big issues are unresolved in many countries,

such as:

- the lack of policy orientation (fiscal policy and public land

policy) compared with other sectors;

- the strong resistance to transparent procedures and independent

audit in many countries because of vested interests of political

leaders and officials at central level and in local government;

- power-related political interference in public land acquisition

and public land allocation;

- the high incidence of state capture through land grabbing,

illicit land swaps, and corrupted concession arrangements by

powerful people;

- the low awareness of public property problems at all levels –

government institutions and international development organizations;

- the lack of information on what is where and where is what;

- the weak statistical information, reliability of information,

and analysis on state property, e.g. transfers to local governments,

state and municipal enterprises and trusts;

- the fragmented and inefficient institutional arrangements

combined with the lack of clarity of role and functions of

stakeholders at central and local government level.

By its nature, the whole history of public land management has been

ad hoc and opportunistic. This is because decisions about its use are

power-related rather than institutional. So far, the institutions of

good governance have not matured to the point where they are capable of

handling the vast amount of data needed to manage public land

effectively. At present, we are conditioned by the consequences of the

fact that this is what the government of the day in a particular society

has at its disposal to use as an immediate tool for meeting some

agreed-upon problem.

The possible impact of illicit misappropriation of state assets on

development processes and poverty eradication is enormous. It has both

direct and indirect negative impacts on development.

Weak governance in managing public property assets shows enormous

consequences on all sectors – economic development, poverty alleviation,

the environment, political legitimacy, peace and security, and

development cooperation. It has both direct and indirect impacts on the

security of common property rights, on access to land and on revenue

generation for the state. It directly diverts public funds and assets

away from the public sectors into the hands of the select few. Moreover,

it directly undermines the public’s trust in the ruling government and

governance processes – a factor essential for good governance and

lasting development reforms. Corruption and the looting of state assets

at the top sends a negative signal to the other civil servants and can

encourage a corrupt culture and unethical conduct throughout the civil

service. Without a strong, competent and clean civil service,

development reform is bound to fail.

Box 1

Political corruption and the looting of state property assets is

a development issue

Political corruption in the form of accumulation or

extraction occurs when government officials use and abuse their

hold on power to extract from government assets, from government

revenues, from the private sector, and from the economy at

large. Political corruption takes place at the highest levels of

the political system, and can thus be distinguished from

administrative or bureaucratic corruption. Bureaucratic

corruption takes place at the implementation end of politics,

for example in government services such as land administration

and the tax department. Political corruption takes place at the

formulation end of politics, where decisions are made on the

distribution of the nation’s wealth and assets and on the rules

of the game.

Extraction takes place mainly in the form of the looting of

state assets, soliciting bribes in bidding processes for

concessions, procurement, in privatization processes such as the

disposal of state land and in taxation or negotiation of

concession fees. Extracted resources (and public money) are used

for power preservation and power extension purposes, usually

taking the form of favouritism and patronage politics. It

includes the politically motivated disposal of state property

resources. By giving preferences to private companies for land

concessions (agro-industry, forest and extractive industries),

the perpetrators can obtain party and campaign funds, and by

paying off the governmental institutions of checks and control

they can stop investigations and state asset audits and gain

judicial impunity.

Source: Adapted from Utstein Resource Center

(www.u4.no). |

2. GOOD PRACTICES

Only a few countries have tackled explicitly and comprehensively the

deficiencies of their public land management systems and only incomplete

information are available on such reform processes. This makes the

lessons learned from experience rather limited compared with reforming

land administration systems, which many countries have embarked on with

support from the international community (Table 2). Good practices for

reforming public land management are designed to regulate the topics

covered in the following sections.

|

Country cases in a learning

environment |

Action and lesson learned

|

|

Canada Monitoring guide:

www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/common/us-nous_e.asp

DRFP:

www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/dfrp-rbif |

Overall reform of the public sector. Consequently, transparent

public asset management is based on a comprehensive

accountability system and has been implemented at all levels.

Guiding principle is to acquire, manage, and retain real federal

property only to support the delivery of government programs and

in a manner that is consistent with the principle of sustainable

development. The design of the Directory of Real Federal

Property, DRFP, with its functionalities and standards as well

as the audit guide and the monitoring guide could serve as good

practice in other countries. |

|

Egypt Draft Policy Note, World Bank, April 2006 |

Reform of the public sector and reform of state land management

has been initiated during the last years and valuable material

has been developed with support of the World Bank. There is

broad support for the state land reform from highest political

level. Internal and external dialogue is a strategic component

of the learning process. Policy orientation within a long time

frame is defined before the legislation will be amended. Several

institutional and organizational scenarios with the discussion

on pro and contra are supporting the decision making process.

There are some difficulties in integrating military’s and

security’s interests. |

|

Cambodia Multi-donor supported Land Management and

Administration Project

LMAP project documents |

Tackling of the huge overall state land problem in a

post-conflict and post-transition country by enabling

legislation (incl. by-laws in state land inventory and mapping,

reform of economic state land concessions, distribution of state

land (social concession), land policy formulation, country-wide

reform of the land sector, inter-institutional arrangements

(land policy board), delegation of power to provincial

committees, implementation and capacity building with

international support.

However; state land problems reflect power relation at the

highest level of the government. Tackling the problems goes far

beyond project measures. |

|

Central European Transition Countries Urban Institute,

2006

Open Society Initiative, 2003 |

Political and professional debate on public sector reform around

political decentralization, re-assignment of public functions

and devolution of state-owned assets. All assets connected to

functions assigned to local government should be transferred.

Special issues are the legislative process, the scale,

sequencing and timing of the transfer of public land, the

competencies of local government for acquisition, management and

disposal of public land, the related rules for financial

management of public assets, introducing standardized accounting

practices, new forms of internal and external audit and

transparency, and rules for minimizing conflicts of interest. |

Table 2 - Cross-Country Reform Comparisons

3. PUBLIC LAND INVENTORY AND INFORMATION SYSTEM

One central point has to be made. No accountability, transparency and

effective management is possible without adequate knowledge about the

qualities and quantities of public land, related legislation and

regulations (where is what and what is where). Many governments share a

common problem. They do not know where and how much public property they

own and what rights are attached to it, where all of the existing

information is located in a complex institutional environment, and how

complete, accurate, reliable and relevant the information is for

planning and decision-making. There is wide divergence in approaches and

institutional arrangements for managing state land information. Some

governments implement a central database and others opt for departmental

or decentralized information systems. Ultimately, all public land should

be properly registered. As an intermediate step and complementary

management tool, there are good experiences with public land

inventories. They contain all the information on public land for

management purposes but do not replace the register.

In a first approach, compromises could be accepted in terms of survey

accuracy but not in terms of regulatory content. Most countries have

established some sort of land information system but, perhaps

surprisingly, only very few are showing good examples and

functionalities of information systems for the specific requirements of

public land management (Treasury Board Canada 2000, KAMCO South Korea

2006). Comprehensive, easy-to-access and easy-to-use systems have been

established in only a few countries.

4. PUBLIC LAND POLICY AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

A public land policy provides fundamental directions. However, it has

to be complemented by a law on public land management or a similar piece

of legislation that should provide parameters as to what can and cannot

be done with state land, and spell out the fundamental responsibilities

of government and the necessary decision-making processes as well as

setting general parameters for allocating public land. A guiding

principle of the government in acquiring, managing and retaining public

property is that it should only do so to support the delivery of

government programmes and in a manner that is consistent with the

principles of sustainable development, poverty reduction and good

governance. Within this context, public property must be managed to the

maximum long-term economic advantage of the government, to honour social

and environmental objectives, to provide adequate facilities for users,

and to respect other relevant government policies.

The essential policy goal is to set forth the criteria for deciding

who is to benefit from how much of these resources, for how long and for

which purposes. At the very least, the policy of public land management

has to clarify:

- policy goals, especially state land policy for implementing

ecological, social, economic and cultural goals;

- a clear commitment of the government and the outline of an

action plan;

- a statement that the public land asset is held in trust for the

people;

- principles for regularization of public land;

- how it will guarantee security of common property rights,

indigenous land rights and resource rights on public land;

- the framework for the institutional jurisdiction and public use

by different authorities;

- devolution of public property to local government (if needed for

its portfolio);

- the framework for special-purpose cooperation, public–private

partnership, and land trust;

- transparent principles for the allocation of state land, and for

what purposes;

- coherent rules and regulations for compulsory purchase

- principles of fiscal management, performance reporting and

audit;

- accountability and transparency requirements for managing public

land.

Reforming the management of public land must contribute to a basic

set of development principles, namely reduction of severe poverty, the

achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and progress in

good governance and transparent fiscal management of the public sector.

The development objectives of growth, poverty reduction and revenue

generation need to be balanced and made compatible in designing the

strategy for public land management. As in many countries there is still

not much awareness and interest in properly managing public land, the

question will always be who will define the development objectives and

guide the policy development for public land.

Some good experiences have been made by nominating a high-level,

inter-ministerial board such as a national land policy board or public

land commission for overseeing the process. Examples are the Higher

Committee for State Land Management (Egypt), the National Land

Commission (Kenya), the Council for Land Policy (Cambodia) or the

National Superintendent of State Property Peru (SBN 2000).

The basic regulatory framework on public property should focus on

fundamentals to limit discretion and, thus, abuses. It should provide

the principles and not very detailed rules or terms, which are better

left to executive regulations or contracts.

Land law and public land law reform need fresh attention because much

legal reform is often concerned with formalization of “informal” land

rights in favour of the state (Bruce et al., 2006). For example,

customary systems are not informal, but represent an alternative

formality. A regulatory framework (land law, law on public land, by-laws

or regulations) is required for the following critical public property

areas, which often show weak governance realities:

- registration of public land and inventory;

- public land classification and reclassification;

- public land disposal and exchange;

- compulsory purchase, valuation of public land, and compensation;

- regularization of bundle of rights;

- resettlement;

- land concessions, leases and contracts;

- law enforcement and public land recovery (in cases of illicit

allocation);

- audit and fiscal control.

Nevertheless, we do not need to wait for a comprehensive and complete

regulatory framework for achieving better results towards improved

public land governance. Most importantly, a public land inventory, an

inter-institutional technical secretariat, and a board for overseeing

the process combined with accountability and transparency are the

ingredients for making a start. Law and legislation are just part of a

process, not the end.

Regularization is an important good governance tool for avoiding land

conflicts, human rights violations and eviction. In many countries,

there is no straightforward inventory or registration process for public

land visible for many reasons.

There are numerous cases of invasion, informal urban and rural

settlements, appropriation of public rights of way, residual claims, and

unclear overlapping or conflicting interest between communal properties

and public land. Therefore, a process of regularization is recommended

based on a participatory approach with transparent rules. Legal

instruments vary from country to country. They include statutes, decrees

(presidential, ministerial, federal, state or provincial, and

municipal), ordinances and by-laws of local governments, regulations and

government contracts. These various legal instruments define who has

enforcement powers, and under which legal instruments. They also

establish the legal basis for sanctions or charges as well as the

penalty provisions, all of which are central to the enforcement system.

However, which ones are involved in any given case are usually

determined in a rather ad hoc way at best and in a self-interested way

at worst. There are several important issues in the design and operation

of a successful compliance and enforcement system. Enforcement involves

a number of components (legislative groups, legal instruments,

enforcement agencies and courts) that act independently, or are

autonomously administered, yet must function together to be effective

(for example Public Land Encroachment Committee Thailand, PLEC). There

is also a relatively broad range of enforcement responsibilities

involved in the administration and management of public lands and land

resource utilization contracts. Compliance and the effectiveness of

enforcement depend critically on the conditions and clarity of the

legislation, on the strength and clarity of the commandments written

into these laws, and on all four components working together.

Anticorruption strategies will have to consider whether to establish

a separate institution such as an anti-corruption agency to deal

exclusively with corruption problems, whether to modify or adapt

existing institutions, or some combination of both. A number of legal,

policy, resource and other factors should be considered in this regard.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption requires the

establishment of such agencies. Nevertheless, anticorruption commissions

are problematic when political leaders are only responding to demands

from international donors. In such countries, policy-makers can ignore

domestic demands for reform and enact minimal reforms to satisfy

external agents. This minimum may be nothing more than the establishment

of an anticorruption commission, an office of the ombudsman, or an

antifraud unit without enabling legislation, competent staff, or a

budget.

5. DEVOLUTION OF PUBLIC LAND

Decentralization reforms are one of the fundamental components of

public-sector reform and democratic development. In many countries in

transition, property devolution was simultaneously implemented with the

dismantling of the socialist ownership model in the context of

privatization and restitution. Devolution of public property was and

still is discussed extensively during the political reform process, and

arguments are exchanged for and against property devolution. (Open

Society Initiative, 2003) There can be no real local autonomy without a

sound economic base. Significant own resources are required for fiscal

decentralization, and public land can be an important source of

municipal revenue. The most common arguments against devolution were the

risk of inefficient management of public land and the lack of

capacities. Useful experiences for countries still facing the reform

process have been made during the last two decades. (see Republic of

Albania 2001, law on the transfer of state public immovable property to

local government units). The challenge of governance and accountability

at local government level is big and similar to the challenge at central

government level. Basic principles and clear rules must be defined and

enforced for avoiding weak governance and corruption in managing public

land at local level. At local-government level, special attention must

be given to the sometimes non-transparent and non-accountable behaviour

of local leaders. Examples can be: corrupt practices of land disposal

and land conversion (less than market value and favouritism); misusing

the instrument of compulsory land acquisition for undercover purposes;

the shift of public ownership to municipal enterprises (where surplus

public land and the revenues could disappear in a non-transparent

system); and manipulating zoning combined with land conversion for

private gain.

6. PUBLIC LAND AND THE COMMONS

Common property regimes are management systems where resources are

accessible to a group of rights holders who have the power to alienate

the product of the resource but not the resource itself. Common property

can be legally owned by the state, a community or an organization.

Within this legal framework, a group of traditional rights holders

manages the resource exclusively to preserve and enhance its long-term

productive capacity for the benefit of all current and future members of

the group. All members share reciprocal rights and duties that can only

be amended by collectively binding decisions. It is particularly useful

to look at which users have rights of access, withdrawal, exclusion,

management and alienation, and for what uses. Access and withdrawal are

considered use rights, while management, exclusion and alienation are

rights of control over the resource. “Ownership” is often conceived as

holding the full bundle of rights. From this listing of the bundle of

rights, it is already apparent that state common property is much more

complex than simple ownership. The concept of land resources being

divided into mutually exclusive “properties” is gradually giving way to

one of being a mutually inclusive set of “partial” interests. Much of

the innovation is a result of the continuing evolution in managing

scarce resources, natural and human-made. It would be much more resource

efficient if a number of individuals and/or enterprises could discover

non-competing uses of the same resource base. Yet all too often

government agencies fail to recognize community-based land and resource

rights on state land. There has been the steady appropriation of many of

the most valuable local common properties by the state and their

re-designation as state or public lands. This has been undertaken on the

assumption that the state is the only proper guardian of such properties

and the rightful primary beneficiary of their values, and often on an

assumption that these same properties are in any event weakly tenured at

best. Even in countries where public land is registered, there is

generally no registration of partial interest and recognition of the

bundle of rights. The regulatory framework must provide a clear legal

base for the registration of partial interest over space and time and

the recognition of the group. Co-management models (e.g. through

participatory land-use planning) for clearly defining the role of the

state and the role of the local group in managing the public land

resource on the ground should complement the regulatory framework.

7. INTEGRATED LAND USE MANAGEMENT

The major objective of land management is matching the land rights

with land-use rights and land-use options for achieving sustainable

development objectives. International agreements are affecting national

legal systems, and national and local land-use systems are paying

attention to the urgings of international declarations and conventions.

In the context of managing public property it is clear that the legal

status and classification of public property, present land use and the

desired (best) land use options are interlinked and should not be dealt

with separately in policy discussions or in the operation and delivery

of public property. Integrated land-use management and public land

management are closely connected and should be seen as complementary

objectives in order to provide win–win development options. There is

generally a lack of knowledge and awareness of this broader implication

in rural as well as in urban land management. Examples of the linkage

between legal status and land use are:

- regularization of informal settlements on public land for

supporting upgrading programmes;

- providing public land for housing the poor and for rural

landless;

- facilitating exchange of public land (land swap) for development

or conservation purposes;

- guiding acquisition and disposal of public land for achieving

broader development objectives;

- land readjustment combined with public land banking and for

rural and urban development;

- land exchange for facilitating zoning and land-use regulation;

- co-management models (state and local communities) and

participatory land-use planning for securing resource rights in time

and space.

8. COMPULSORY PURCHASE

Compulsory purchase is one of the most extreme forms of Government

intervention. Debates about its application can therefore serve as a

prism for viewing deep changes of society and governance. There are

current signs of crisis in several countries that stem from a growing

disparity between law and practice.

There are significant legal differences across countries, especially

between Statutory and Constitutional Law countries. In most countries,

statutory law is the major determinant of expropriation powers and

compensation principles. In addition, some countries grant property

rights for constitutional protection. Europe has a “meta-constitution”

in European Convention on Human Rights, 1953 with Protocol 1 protecting

property rights. Nevertheless, differences in constitutional protection

matter much less than legal scholars assume.

Compulsory purchase is articulated in almost every nation’s

constitution, either specifically or broadly. Most countries supplement

the constitutional basis for the power with additional laws and

regulations that explain exactly how the power may be used through

public law or administrative law. The commonly accepted purposes for

applying compulsory land purchase are the “public good” or “public

interest.” Other obvious goals” allow for some legal flexibility in the

use of the power in some countries such as redistributive land reform

and compulsory land acquisition for private development. Usually the

national government has the special mandate to use the power of

compulsory purchase. In some countries, local government (provinces,

states, districts, counties and municipalities) can also use the power,

as well as parastatal organizations supplying necessary utilities. A

variety of bodies within one country may have the power to undertake

compulsory purchase processes, each with their own regulatory

guidelines.

If all of these regulations are not synched up, and a coherent

national policy is not created by a central oversight body, numerous

situations of injustice and insecurities might occur. The dimensions for

determining the “public purpose (public interest)” in land-expropriation

law and policy should be determined by (1) land use type (urban or rural

function), Operator type (state parastatal, private), (3) Public

beneficiary, (4) Plan-based specificity (requirements for approval, (5)

Permitted time range for implementation

Most discussions of public purpose pertain only to the initial use.

The issue of “public purpose” is heightened when questions are posed

over time:

- The permitted time frame for implementing the public purpose

- Rules about what should happen if the public purpose is not

implemented Rules about change of from the initial public purpose

into a new public purpose after the first is no longer needed

- Rules about change from the initial public purpose to a

non-public purpose

A central component of compulsory acquisition and compensation

process is the right to contest the loss of one’s property. Appeals

provide necessary oversight, a crucial check on state power. Supervision

by a reviewing body can stop corruption, correct error, and insure that

justice is done.

Appeals about the purpose can include the reason underlying the

appeal or may concern a person’s conviction that their parcel does not

need to be acquired for the project. Appeals about the process may be

about corruption, improper timing, processing of claims, negotiation

procedures, delay in payments, etc. Because these claims often have to

do with bad faith or incorrect actions on the part of the acquiring

authority, a separate complaints process might be established for

immediate, expedited review separate form substantive claims. Appeals

about compensation are by far the most prevalent, and may best be dealt

with through alternative review mechanisms. People whose land is being

acquired by the state should be given help to understand every aspect of

the process. They may need assistance contesting the decisions and

actions of the acquiring agency, getting second opinions on the value of

their land, and ensuring that compensation is paid. Legislation should

address the imbalance of power by providing mechanisms to assist people

to become better advocates for themselves.

|

Case Study Ethiopia: Some Major findings

Authorizing Act: Proclamation 455/2005 for Federal & 9

semi-autonomous Provincial Governments

- but no Federal Regulations nor State Directives &

Guidelines for implementation had been developed

- Large number of expropriations, ‘Public Purpose’ is

widely applied, including for private commercial purposes

(as per Proc 455)

- No right of appeal against the ‘purpose’ of the

expropriation, farmers have right of appeal (against

compensation) to regular courts, but evidence of courts

having little knowledge of the law (455) and giving

inconsistent decisions

- Township/Urban Expansion represents a large proportion

of expropriation cases

- Availability of suitable land for substitution /

resettlement is severely limited and generally of poorer

quality, therefore cash compensation is payable in most

cases

- Compensation payments were often delayed or received

after eviction

- Farmers have little knowledge of their rights

- No compensation paid for ‘communal’ land

- No compensation paid for indigenous trees or land not

‘worked

- Farmers without ‘holding certificates’ have received

less compensation

- Assessment of compensation was by (unskilled) committees

due to lack of capacity

- Evictees were rarely represented

- Acquiring Authorities often had insufficient finances,

delayed payments, non-payments, manipulating formulae to

meet budgets, and instances of money raising events

(deductions from employees wages)

- Compensation payments too little to sustain life after

eviction, or poorly invested (empirical evidence shows

- 57% increase in poverty levels following expropriation

Source: Andrew Hilton FRICS, FIG Seminar on

compulsory purchase and compensation, Helsinki September 2007 |

9. ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY

Good governance and anticorruption measures in public land management

can take a variety of forms, and their adequacy will depend on the

prevalence of the respective types of corruption and on the political

and institutional environment of the country in question. As an entry

point for assessing and discussing the current state of the art of

public land governance in any country, one could best check the

Governance Research Indicator Country Snapshot (GRICS) rule of law

dimension (WBI, 2005). The rule of law dimension reflects the power

relations in a country and is directly related to the quality of

managing public assets. This is particularly important where political

corruption occurs, where institutional and enforcement capacity is

likely to be weak, and where, consequently, the timing, sequencing and

design of reform are crucial to ensuring the feasibility and

sustainability of the reform process. There is the need to curb high

levels of administrative discretion, which, coupled with a lack of clear

rules and regulations, are conducive to the persistence or facilitation

of phenomena such as land capture, the corrupt allocation and management

of public land, and land allocation more generally. Most of the causes

and conditions contributing to weak governance and corruption in these

areas are best and most sustainably addressed by comprehensive

institutional reform and capacity building and concern performance

evaluation, regular auditing and reporting, service orientation,

budgeting and access to information, and the nomination of an

inter-institutional oversight board. Especially in countries with

political corruption, the design and implementation of good governance

and anticorruption strategies is a politically sensitive issue, with

powerful interests standing to lose out in the process and with results

manifesting themselves in the medium to long term, rather than in the

short term.

Some “new public management” (NPM) countries such as New Zealand,

Canada and others have established legal and operational requirements

for easy-to-access performance and accountability reporting on state

assets, including public land. However, there is also good reason why

countries in political reform processes should be careful in adapting

NPM. It could lead to the fragmenting of an already weakly integrated

state and/or accelerate the waste of public goods.

10. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Even advanced economies have generally managed their public land

assets very poorly in the past, and many countries are only now

launching reform efforts and improvements. This new interest is mainly

driven by public-sector reform and fiscal reform in some countries, or

devolution of state assets from central to local government or the

challenge of governance and accountability in other countries. There are

numerous good practices, but such experiences are scattered, not

systematically analysed, and not easily accessible or properly

documented. There is an enormous need and interest not only for sharing

experiences about work in progress in all countries but also for

tailored capacity-building opportunities in the effective management of

public land. Public land will continue to take on greater social and

economic significance. In doing so, the related institutional, legal and

operational arrangements that should secure multiple interests in

specific parcels will take on additional political importance. We have

not yet scratched the surface on crafting new institutional arrangements

pertinent to land in this broader sense (Bromley).

Reforming the management of public land must contribute to deliberate

policy and development principles, namely the reduction of severe

poverty, the achievement of the MDGs, and progress in good governance

and transparent fiscal management of the public sector. The development

objectives of growth, poverty reduction and revenue generation need to

be balanced and made compatible in designing the strategy for public

land management.

The following steps highlight and summarize the major points made

towards reforming the management of public land:

- Create awareness and recognition at the highest level in central

and local government, development institutions and civil society:

What could be the driving force for reforming public land

management? (For example, public sector reform, MDGs, poverty

reduction strategy papers, governance reform, and social justice.)

- Develop a good deliberate policy around how governments should

intervene in public land management and land markets: Governance

checks could be good starting points for understanding the scope of

problems to be solved and discussion of principles and options on

managing public land.

- Develop and reform the regulatory framework: Reviewing,

complementing and making the legal framework coherent, providing

mechanisms for enforcement and for the right to access information.

- Develop and apply a comprehensive accountability chain:

Performance benchmarks, fiscal control, internal and external public

land audit, conflict of interest rules, and interacting with

anticorruption framework of the government.

- Develop transparent fiscal management procedures: Valuation of

public land and accounting (eventually accrual accounting), revenue

transparency, and reporting. Adapt the IMF guide on resource revenue

transparency to management of state land resources (IMF 2005)

- Develop alternative institutional and organizational scenarios

for the acquisition, management and disposal of public land: Broad

discussion of pros and cons for centralized, decentralized, mixed

custodian models or special purpose state cooperation.

- Nominate high-level body for overseeing the decision-making

process and for control: For example, inter-ministerial public land

board with trustee function of the government.

- Develop the regulations, technical tools and standards for the

registration of public land (and associated land rights) and land

inventory and develop a manual for practical implementation

- Design and implement a capacity building strategy and specific

training modules for professionals involved in managing public

property.

- Mobilize complementary governance support: General Auditor,

Judiciary and / or Anti-corruption Agencies. Land Administration

professionals must be protected from power pressure and vested

interest groups in government.

The role of the international community is first of all to be aware

of the importance of public land asset for development. There is a need

to integrate public-land matters much better in the formulation of land

policies, public-sector reform and fiscal reform initiatives as well as

in public-good policies.

There is certainly a need for more research on dealing with the

recognition and registration of bundle of rights on public land, on

global analysis and on innovative institutional models for the

acquisition; management and disposal, for example, special-purpose

agencies or public–private partnership models. There is a need to

develop a compendium of state land laws and regulations and a sourcebook

on adaptive strategies and operational models. Specific training modules

for effective management of public land should be designed and offered

by the international community, and curricula on land administration

should be updated. Global statistical information, indicators and

analysis on public land at central-government and local-government

levels is extremely weak compared with other relevant indicators on

sustainable development. Creating a global learning network for

exchanging information and developing a knowledge base for effective

public land governance would certainly contribute to sustainable land

management.

Effective and transparent management of public land is a critical

aspect of land governance, respecting human rights, rule of law, poverty

reduction strategies and revenue generation.

REFERENCES

Bromley, D. 2007, Land and economic development: new institutional

arrangements for the 21st century. Cambridge, USA, Lincoln Institute of

Land Policy. (also available at

www.lincolninst.edu).

Bruce, J.W., Giovarelli, R., Rolfes Jr, R., Bledsoe, D. & Mitchell,

R. eds. 2006. Land law reform, achieving development policy objectives.

Washington, DC, World Bank.

Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE). 2006. Global survey

on forced evictions, violation of human rights. Geneva, Switzerland.

(also available at www.cohre.org).

FAO 2007, Good governance in land tenure and land administration,

land tenure studies no. 9, Rome

http://www.fao.org/nr/lten/abst/lten_071101_en.htm

FAO bulletin land reform 2007/2, articles on good governance in land

tenure and state land management, including case studies, Rome

ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/010/a1423t/a1423t.pdf

FAO/FIG/CNG International Seminar on State and Public Sector Land

Management, 9-10 September 2008, Verona, Italy,

www.fig.net/commission7/verona_fao_2008/proceedings.htm

IMF 2005, Guide on resource revenue1 transparency, implementing the

Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency

http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/2007/eng/051507c.pdf

IUCN 2007, Compendium of Land Use Laws for Sustainable Development

Korea Asset Management Cooperation KAMCO 2006, Principle of State

Land Management, Second edition, Seoul, South Korea.

Open Society Initiative. 2003. Transfer of public property to local

governments in central Europe (available at

www.lgi.osihu).

http://www.mftf.org/resources/index.cfm?fuseaction=siteDetail&ID=188

The Urban Institute 2006, Managing Government Property Asset,

International experiences, Washington DC

Treasury Board Canada. 2000. Property management framework policy

(available at www.tbss-ct.gc.ca).

http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pubs_pol/dcgpubs/RealProperty/mfp-eng.asp

World Bank Institute (WBI). 2005. Governance, Research Indicator

Country Snapshot (available at

http://info.worldbank.org).

http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp

Zimmermann, W. 2006, Challenges of effective state land management,

Land policies and legal empowerment of the poor, workshop document,

World Bank Washington DC

Comment

for Reader

The topic on public land management is still controversial. Therefore

any comments, suggestions and recommendations to this article and topic

would be most welcome. The author is interested to receive your comments

and pass them on to FIG Commission 7 to help the Commission in its work

on this important issue.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Willi Zimmermann

Academic experience: Geodetic Engineer MSc., University of Karlsruhe,

Germany

Practical experience in Germany: State of Baden-Wuerttemberg, Government

Agency for Land Development and Land Consolidation

International experience: Vast experience of 25 years in land policy,

land management and access to land, in designing strategies as well as

in practical implementation. 25 years in development cooperation with

GTZ (German Agency for Technical Cooperation) and other international

organizations as land policy / land reform / land management advisor.

Short term and long term assignments in Southern and South Eastern

Europe, Africa, Near East, South East Asia and Latin America.

Guest lecturer at the International Postgraduate Program Land Tenure and

Land Management at Technical University Munich.

CONTACTS

Willi Zimmermann

International Land Policy Advisor

Nordplatz 6

04105 Leipzig

GERMANY

E-mail: wita21@gmx.net

|