Article of the Month -

August 2008

|

Conceptual Framework for Governance in Land

Administration

Mr. Tony BURNS and Dr. Kate DALRYMPLE, Australia

| |

Tony Burns |

Kate Dalrymple |

|

This article in .pdf-format

(16 pages and 229 kB)

This article in .pdf-format

(16 pages and 229 kB)

1) This paper has been prepared for

and presented at the FIG Working Week in Stockholm, Sweden 14-19 June

2008.

Key words: land administration, good governance.

SUMMARY

In this new millennium, governance has gained significant attention

on the global development agenda and is often considered a fourth

dimension of sustainable development, adding to economic, social and

environmental dimensions. Implementation strategies to address

sustainable development aspirations and to meet Millennium Development

Goals must be tailored to address varying development needs. Mobilizing

the land sector is considered a principle focus for poverty reduction

and a key development strategy in many countries. Land administration

and management systems in particular, are responsible for providing

tenure security and access to land for all. In addition these can

provide accessible and equitable systems to mobilize land resources that

ultimately assist in the alleviation of poverty. Good governance within

land administration and land management institutions is essential for

sustainable development both in terms of operational longevity,

equitable stakeholder participation and benefits, and consistency in law

and policy implementation.

Land administration is often perceived as one of the most corrupt

sectors in public administration. Land itself, considered a primary

source of wealth, often becomes the trading medium and motivation for

political issues, economic and power gains, and self fulfilling

interests. The need to ensure there is good governance in land

administration is thus very important. A key theme in the land sector

among development professionals, policy makers and academics, is how to

address governance within land administration. Current research and a

draft Conceptual Framework design are presented in this paper to

contribute to on-going discussion and provide a tool for focussing

assessment of governance within land administration systems. This work

is being undertaken under a contract with the World Bank.

There is general acceptance that good governance is based on a set of

objectives that include: participation; fairness; decency;

accountability; transparency; and efficiency. Until recently, measures

of good governance and measures of land administration reform

effectiveness have largely developed in separate silos of thought. The

Conceptual Framework consisting of eight objectives aims to reduce this

gap using a range of examples from around the globe. A set of indicators

will be agreed and pilot case studies will test these in late 2008,

however these initiatives are not discussed in this paper. Attention is

given to the first phase of the project which is to establish the

Conceptual Framework for good governance in the land sector.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is almost trite nowadays to say that “land is a fundamental

resource”. The huge social, cultural and economic implications arising

from land rights-based issues, many stemming from poor governance, are

leading international news stories. Whether one is in a developed or

developing nation, land or property is often ones’ most important source

of wealth and security. The concept of land as collateral to mobilizing

capital is increasingly being embedded in developing nations. In

addition to private wealth, the state economy, particularly at the local

level, uses land fees and taxes as a significant source of government

revenue. In terms of tenure security, formal recognition of rights can

be vital for ensuring indigenous and other vulnerable groups have access

to land. It can however initiate tensions of uncertainty between

statutory and traditional groups or customs. Often the intense and

conflicting demands on land resources are not well balanced. Land

continues to be the basis of frequent social upheaval. Therefore much

effort has been devoted to developing systems to administer land rights

their use and value.

In most developing countries secure property rights are undermined by

weak governance practices. Overlapping laws and regulations, weak

institutions, limited accountability, and incomplete property

registration systems create a fertile environment that lacks

transparency. This environment gives rise to petty corruption as well as

grand misuse and/or misappropriation of public resources. Petty

corruption starts with low level government officials working in

registration and taxation agencies seeking informal payments. This

increases the cost of doing business and undermines the business

environment. There are higher stakes where public resources are

concerned, as weak governance in land administration enables political

elites and senior government officials to illegally grab state

properties, seeking large bribes in return of leasing or transferring

state properties to investors. Often these acts also involve by-passing

of development controls which can seriously affect vulnerable groups

whom are unable to defend themselves or are unable to demand appropriate

compensation. Weak governance will affect the poor in particular and may

leave them marginalized and outside the law. Good governance in land

administration is central to achieving good governance in society.

|

‘Senior politicians and public servants in cities all over

the world manipulate or ignore the law and administration

relating to land allocation and development so as to line their

own pockets and those of their families, friends and political

allies’ (McAuslan 2002:27). |

Factors associated with governing land administration are numerous

and complex. Untangling these factors, finding a balance towards

cooperation between private, state and other interest groups and

applying contextually appropriate concepts of good governance in land

administration is being attempted in this current World Bank study. The

scope of the study is much broader and more comprehensive than what can

be delivered in this paper, the process in developing the Conceptual

Framework, which is presented, may be considered as important as the end

result. The process has involved developing a draft Conceptual Framework

and indicators to measure governance in land administration; testing

this draft framework and the indicators in five country case studies;

analysing the results; and finally presenting recommendations of a

Framework that will be useful for assessing governance in nations around

the globe.

Developing the Conceptual Framework is an ongoing process. Initially

it is shaped by desk studies of conceptual and empirical material to

provide an overall project approach and deliver a comprehensive

explanation of each objective that describes governance in land

administration. It will be developed through open discussions, case

study pilots in a sample of diverse countries and analysis of the field

results. In this paper, we are able to present the key concepts of the

study and approach, and an initial set of guiding objectives to consider

in the assessment of good governance in land administration.

2. KEY CONCEPTS

The essence of land administration typically involves processes that:

manage public land, record and register private interests in land,

assess land value, determine property tax obligations, define land use

and management governance systems, and support the development

application and approval process for land use. Land administration

systems should perpetuate policies of tenure security and access for

all. Land management on the other hand is associated with the activities

on the land and natural resources, including such activities as land

allocation, use planning and resource management, simultaneously

considering some inherent aspects of land administration. Land

administration systems provide a set of tools that support land

management. These tools typically operate within a country specific

framework established by land policy and the legal, social and

environmental background of a particular jurisdiction (Burns 2007).

During the last decade, a common understanding and practice of land

administration has evolved. Recognising there is no blue print or ‘one

size fits all’ model; there may be some applicable ‘best practices’

associated with the different system tools. Using land administration

principles as a platform, how does one then adopt principles of

‘governance’ to shape a Conceptual Framework, particularly one that will

be used as the scope to measure performance? An appreciation of the

separate silos of governance principles is required and then combining

these using an understanding of existing operational encounters and

functional arrangements.

The introduction of governance principles attempts to capture a more

holistic approach to measuring land administration than purely

quantitative measures of effectiveness. Momentum for incorporating

governance in the development agenda has been building over the past

decade highlighting the importance of governments and corporate

institutions to commit to socially and economically responsible

sustainable development. Good governance is recognized as a platform for

achieving development potential, implementing effective and efficient

systems and ensuring good management through all levels of society. The

World Bank Institute defines governance as:

|

…“the set of traditions and institutions by which authority

in a country is exercised. This includes (1) the process by

which governments are selected, monitored and replaced, (2) the

capacity of the government to effectively formulate and

implement sound policies, and (3) the respect of citizens and

the state for the institutions that govern economic and social

interactions among them.” |

Other organizations have developed their own governance definitions,

some more widely applicable, “the process of decision-making and the

process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented).”

(UNESCAP)

It is even more difficult to define ‘good governance’. Therefore it

is generally accepted that good governance is based on a set of

principles that include: participation; fairness; decency;

accountability; transparency; and efficiency. Often references are also

made to responsiveness, consensus orientated, equitability,

inclusiveness (UNESCAP) and subsidiarity. There is an increased agenda

on embedding ‘good governance’ into programs, projects and the

functioning of institutions, some attempts have been made to integrate

these principles within land administration reform strategies.

The most definitive efforts to apply the principles are reflected in

FAO’s recent Land Tenure Series Publication, “Good governance in land

tenure and administration” (2007). Prior to this UNHabitat launched the

Global Campaign on Urban Governance in 1999 to support the

implementation of the Habitat Agenda goal of “sustainable human

settlements development in an urbanizing world.” A key outcome of this

campaign was the Urban Governance Index (UNHabitat 2004). Governance is

an integral feature of improving strategies to meet Millennium

Development Goals. As a result the Oslo Governance Centre was

established as part of the UNDP’s global policy network for democratic

governance under the Bureau for Development Policy, and other

organizations are following suit. Other projects and activities of

organizations such as IFAD, IFPRI, ILC, and FIG are contributing to the

dialogue for innovations on improving governance in land administration.

Donor governments and agencies also have a high stake in developing

analysis tools for governance in their aid programs where land sector

components are often substantial. An example of this is the Millennium

Challenge Account that attempts to pre-qualify countries to determine

their eligibility for development assistance using five key principles

of good governance. These good governance principles are: free and fair

elections; independent judiciary and the rule of law; freedom of speech

and press; absence of corruption; and government investment in basic

social services. In a summary paper by Dobriansky (2003), it is stated

that “[t]hese principles constitute the foundations of modern democracy

and create the underpinning to establish capital markets and spur

foreign and domestic investment.” (Dobriansky 2003). While this may be

considered a narrow interpretation of the aims of ’development’, it does

echo the development agenda of numerous governments.

Land governance from the traditional sense can be loosely defined as

the range of political, organizational and administrative processes

through which communities articulate their interests, their input is

absorbed, decisions are made and implemented, and decision makers are

held accountable in the administration, development and management of

land rights and resources and the delivery of land services. Governance

involves an analysis of both formal and informal actors involved in

decision-making, the implementation of decisions made and the formal and

informal structures that have been set in place to arrive at and

implement the decision.

3. APPROACH TO GOVERNANCE IN LAND ADMINISTRATION

Development practitioners of all persuasions recognize the importance

of governance and the rule of law as an essential precondition for

economic and social development. In many contexts, land is identified as

one of the most corrupt sectors together with the judiciary and the

police. Still, given the complexity of land issues virtually everywhere

and the fact that institutional arrangements are highly country

specific, no systematic guidance is available to diagnose and benchmark

land governance and to contribute to improving it over time.

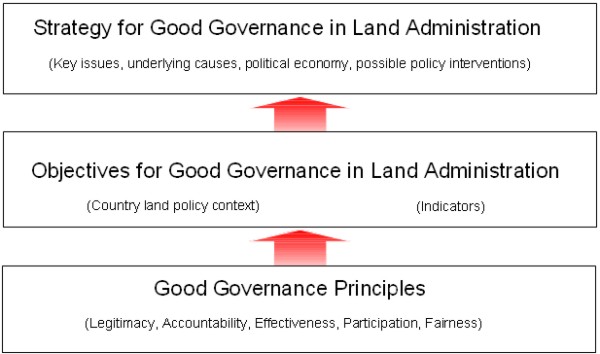

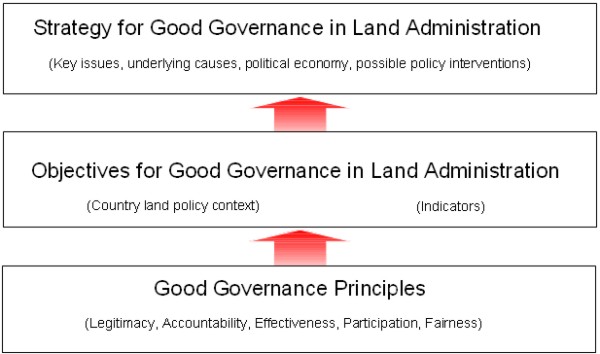

The overall approach used in this study for attempting to achieve

this systematic guidance is summarized in Figure 1. The development of a

conceptual framework began with a comprehensive review of land

administration systems, both formal and informal and of recent project

experience in strengthening land administration systems. Informed also

by the governance literature, central to the Conceptual Framework is the

development of a coherent set of eight statements that set out

objectives for good governance in land administration. These eight

objectives are discussed in Section 4. These formed a platform on which

key policy questions could be developed for country level investigation.

These key policy questions, whilst superficially appearing to be simple

yes/no responses are expected to be far more complex responses of either

‘yes, but’ or ‘no, but’ followed by an explanation of circumstances not

covered by a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. In addition a a set of

numerical indicators that assess the status of the objectives in good

governance are to be developed.

The information gathered in responding to the key policy issues and

quantitative indicators for each of the country case studies will be

used to develop a strategy for good governance in land administration

for that country. Strategies remain based on the global governance

framework but with country specific relevance. In designing the

Conceptual Framework it is important to consider how a country-based

application of the Framework can contribute to informing decision makers

on how to improve governance in land administration for that

jurisdiction.

Figure 1 - Approach to Improving Governance in Land

Administration

Development and governance assumptions can be contextualized greatly

by studying the political economy and addressing the externalities

impacting on various situations. Central to the Conceptual Framework

approach is the two pronged approach stemming from the objectives. One

area concentrates on an assessment of the political economy, primarily

looking at factors affecting the historical and current land

administration arrangements and policies, land market activities, and

other social and economic drivers of development of the country. The

second considers empirical data guided by more quantitative studies that

will result in producing an indicator for comparative assessment,

preferably indicators that can be replicated for comparison over time

and possibly locations, whether these are inter or intra-regional.

Integrating studies of the policy context and an analysis of other

indicators is necessary to evaluate underlying causes or rationales for

a specific quantitative indicator. For example, a low indicator for the

number of registered transactions as a percentage of registered

properties could be due to a number of factors: poorly developed land

markets; low land market activity; little participation in the formal

system (which could in turn be due to high transaction costs and/or an

inefficient land administration system); low community awareness etc.

Governance in land administration certainly does not occur in

isolation to other levels of development and a range of social,

political and economic constructs. The main objectives and development

of the indicators should not be considered solely in terms of land

administration ‘best practice’, but what is “good enough governance”

(Grindle 2007) and what alternatives may be more applicable. The

framework should be approached as an assessment tool that is considered

along a continuum of various stages of achieving good governance

throughout land administration. Therefore, pragmatic and tangible reform

strategies in the context of the stage of development of a particular

country can be derived.

4. LAND ADMINISTRATION GOVERNANCE OBJECTIVES

The focus at this stage of the project is developing a set of

statements that set out a coherent framework of objectives for good

governance in land administration. Indicators will develop as a result

of an accepted set of objectives that can be consistently investigated

at the grassroots level. The following statements for eight objectives

for good governance in land administration have been developed. The

objectives are based on experience with projects in the land sector and

have been refined during the study in discussions with a broad

cross-section of stakeholders and participants in the land sector. The

objectives of good governance were also developed from an understanding

of the implications of ineffective, inequitable and poorly functioning

land administration systems. Weak governance in land administration is a

key contributor to issues of: informal modes of service delivery,

corruption, illiquidity of assets, limited land markets, tenure

insecurity, inaccurate and unreliable records, informal settlements,

unrealized investment potential in property, land speculation and

encroachment, idle and unproductive use of land, inequitable land

distribution, social unrest, and inadequate provisions of

infrastructure. While this list of issues is extensive, it is not

exhaustive. There are numerous more direct and indirect negative impacts

as a result of poor governance in land administration.

Considering these issues and nature of land administration, good

governance in land administration occurs where:

- Land policy is in line with principles of fairness and equity

- A variety of accepted and socially legitimate rights are legally

recognized and can be recorded

- Land management and associated instruments (zoning and

development control plans, conservation plans, etc.) are justified

by externalities and undertaken in an efficient, transparent manner.

- Land administration institutions have clear mandates and operate

transparently, cost-effectively and sustainably

- Information provided by the land administration system is

reliable, sufficient, and accessible at reasonable cost

- Management, acquisition and disposal of public land follows

clear procedures and is applied transparently

- Property valuation serves public and market needs and property

taxation is clear and efficient in support of policy

- Judicial and non-judicial institutions are accessible with clear

mandates and resolve disputes fairly and expeditiously.

Objective 1 – Land Policy in line with Principles of Fairness and

Equity

Land policy is the foundation on which the systems in a country for

land management, land administration and land development are built.

Policy endorsed by a high authority should be based on principles of

good governance focusing on efficiency, equity and accountability.

The implications of weak governance from deficiencies in policy

include tenure insecurity, encroachment and exclusion on access to land,

informal modes of service delivery, limited land markets, increased

administrative corruption and state capture, and increased land

disputes. Functional ambiguity among institutions often equates to

agencies acting unilaterally and out of touch with community

expectations and desires.

Land policy typically has to recognize that there is a variety of

land tenure regimes in a country. In practice, a continuum of tenure

rights can be observed, especially in the context of developing

countries where different sources of law and different tenure regimes

may coexist. There is thus a diversity of tenure situations, ranging

from the most informal types of possession and use to full ownership.

In most countries land is administered in a number of separate

systems or ‘silos’. These silos include the important silo that

registers private rights in land. Other silos that might exist in a

country include those that administer: public land, land reserved as

forest land, land reserved for protected areas, land held under

customary tenure, land used for agriculture and land used for mining.

Much of the uncertainty in rights in countries with administrative

‘silos’ is due to uncertainty regarding the extent of the jurisdiction

for each silo and overlapping silo jurisdictions.

A key strategy to address the problems arising from administrative

silos, particularly in an environment of limited rule of law, is the

adoption of a holistic approach to land administration through policy

formulation and/or legislative reform. National land policies and

comprehensive legislative frameworks have been developed in many

countries, particularly in Africa where about 15 countries have

formulated new land policy and enacted in the past two decades new

legislation which recognizes existing and future private property

rights. This has involved significant effort and consultation. However

this effort has often resulted in little change in the formal

recognition of rights. In Africa a large part of the problem has been

difficulty in funding and implementing the new laws.

An alternative approach to the holistic approach to policy

formulation and legislative reform is developing policy and legislation

in a piecemeal approach. This is the traditional approach to policy

development in developed and developing countries. This approach

involves the development of a policy and legal framework to register or

record a set of specific rights in a defined locality and is typically

implemented by developing procedures and building stakeholder support

through a series of pilot studies.

Objective 2 – Property Rights have Legal Recognition

This objective is concerned with the legal recognition of property

rights, the consonance between the rights recognized by the legal

statutory framework and the rights on the ground that have acceptance

and legitimacy in the community and the enforceability of the legally

recognized rights. The legal recognition of rights is very much related

to power structures in the community.

Informal settlements, informal building and construction and tenure

insecurity are key implications of weak governance in this area. Weak

governance in the legal framework for land opens gaps for speculation,

unproductive use of land, and a lack of clarity in rights leading to

social unrest and land disputes. The economic, social and environmental

implications can have a widespread impact on government and the

community.

There are many projects that have successfully implemented programs

to systematically register rights. These projects cover a wide number of

countries, including Thailand, Lao PDR, Indonesia, Honduras, Peru,

Armenia, and Kyrgyz Republic. The systematic process, which is typically

undertaken as an open process for the whole village or community, is

usually more transparent than the traditional sporadic approach. The

systematic approach provides the metrics for a production process with

checks and balances. A systematic process is also most cost-effective,

particularly where geodetic control or base mapping is required.

A key requirement for an efficient systematic process is the fact

that the teams in the field have clear rules to establish rights. Many

of these rules are based on the recognition of long-term occupation

rather than the provision of documentary evidence. Pilot activity is an

important strategy to build capacity by developing and field testing

efficient procedures, and building stakeholder support. A key lesson

from several projects is that municipal and administrative boundaries

and easements should be defined as part of the systematic registration

process. In many countries changes in other requirements such as

planning norms and standards are necessary before formalization can be

undertaken.

Although there has been success in systematic registration in many

countries, fewer countries have been able to keep property in the formal

system and encourage a ‘registration culture.’ In many countries there

is often a long list of unclear prerequisites for the registration of

rights and frequently there is a great deal of official discretion in

how these prerequisites are interpreted and implemented. One strategy

that has been implemented to address this problem is the establishment

of one-stop-shops (OSSs), where an OSS is a single point of contact that

manages the processes required to obtain the necessary approvals.

An alternative approach to formalization or systematic registration

is to focus on tenure security rather than regularization. This

particularly applies in the case of informal settlements in urban and

peri-urban areas, but also to areas under customary and common property

regimes. An approach based on tenure security might combine: (i) the

provision of both personal rights (such as temporary or permanent

permits to occupy, short term leases) and real rights (freehold, surface

rights, long-term leaseholds); (ii) the provision of individual rights

and of collective rights; (iii) the provision of transferable and of

non-transferable rights.

Community understanding of the land rights that are recognized by law

and the associated processes to give effect to the legal recognition is

essential. The laws need to be consistent with local customs. Gaining an

understanding of community practices and concerns is an important first

step, particularly in countries where the formal system is neither

efficient nor well regarded. Best practice in community awareness

includes a comprehensive web page, a customer relations manual that is

available to all staff, media training for senior officials, a range of

promotional material including posters, brochures and media campaigns on

national and local television and newspapers. In less developed

countries efforts have focused on village meetings and village plays.

Policy needs to be developed for parcel boundaries and the status of

survey records in re-establishing boundaries. One of the dangers of

increasing accuracy and decreasing cost of surveying and mapping

technology is the specification of a standard just because it is

technically possible rather than because it is needed. Experience in

many countries suggests that survey accuracy is not a major concern. No

project in the developing world has been able to implement and sustain

high-accuracy surveys over extensive areas of their jurisdiction. Those

countries that have been successful in registering significant numbers

of titles have tended to concentrate on relatively simple, low cost

survey methods and produced graphical standard cadastral index maps.

Objective 3 – Land Management instruments are justified, efficient

and transparent

Land management and other instruments, including land use planning

and zoning instruments, are justified by externalities and are

implemented efficiently and transparently. The land management and

administration systems become the foundation for the hierarchy of other

instruments which support a wide range of natural resource use rights

for activities associated with land, air and water. These include land

use zoning, site development, allocation and use of air space, the

allocation and use of water resources, and the use and exploitation of

fish, forest, mineral and other natural resources. Each level of rights

in the hierarchy is accompanied by more a specialised land management

governance system because they represent value adding in different

markets and economic systems.

Land management is regulated by imposed land use planning and

associated development restrictions. Effective land use planning must be

in line with community needs and undertaken in a participatory way. The

consequence of poor land use planning is informality as people will find

informal means to cope with their needs, particularly when planning

designs inadequately predict or supply the necessary infrastructure.

Issues affecting land use arrangements, which often directly affect

people’s livelihoods, can result in high levels of social unrest. There

are also often problems enforcing master plans as they are either

developed without due consideration of implementation arrangements and

capacity or developed in a non-participatory approach that meets strong

community resistance. Similarly, zoning restrictions should be justified

by external effects, and determined in a transparent and participatory

way. Regulations and restrictions should be made in line with the

capacity to enforce them.

Other forms of formally recognized rights, such as airspace rights

for apartments have become important instruments for property

development in cities, especially where the supply of approved, serviced

land sites is typically a constraint. However, in many developed

countries and the former socialist republics, the selling off of rights

to apartments without proper governance arrangements has given rise to

significant building maintenance and redevelopment problems associated

with old and unsafe apartment blocks.

Some countries have moved to register water right allocations and to

establish a water trading market to enable water rights attached to land

to be traded, often in a manner that is independent of the land itself.

Water rights are now becoming a major issue in China, India and other

South East Asian countries, with several river systems no longer flowing

and water demand dangerously depleting minimal environmental flows.

Development of controls on many of these rights will be extremely

difficult generally given the lack of or poor state of formal land

records management systems and particularly in regard to planning

schemes and the provision of public assets under these schemes.

In all developed and developing countries there has been a gradual

evolution in the systems to recognise rights for the exploitation of

natural resources. This evolution has occurred in parallel with the

development of systems to recognize private rights in land and in the

wider policy context of the management of common pool natural resources,

the recognition of and disposal of public land, and tax and fiscal

policy. There has been a general trend to separate systems to allocate

and exploit natural resource from the systems to recognize land rights.

An example of this is the policy introduced in the nineteenth century in

most developed countries to separate mineral rights from land rights. A

more recent example is the separation in many countries of water rights

from land rights. The systems introduced to support these policies are

models for many developing countries. The recent initiatives to

recognize and support carbon trading and growing concern about climate

change will add increased emphasis on the need for improved systems for

recording natural resource rights and distributing the benefits from the

allocation of these rights.

Objective 4 – Land Administration institutions have clear

mandates, and operate transparently

Land administration will only operate at an optimum when the roles

and responsibilities of all interested agencies are clear, unambiguous

and followed accordingly. This applies both horizontally between

agencies and vertically between levels of hierarchy, factoring in

private sector and community involvement. Introducing good governance

techniques into public sector organizations often requires widespread

changes. A common approach in land administration reform activities is

to streamline services. This often requires merging of agency

responsibilities into a single “land” agency, introducing new technology

and strengthening human resource capacity. Introducing civil service

standards and codes of conduct are two methods to improve operational

accountability in the area of human resource capacity.

Effective mechanisms are required to ensure the behaviour of land

administration institutions is managed and to eliminate or minimize any

negative social impacts of the services provided. Monitoring

institutional behaviour in the public sector is often a low priority in

developing countries. Without appropriate mechanisms, weak governance

can lead to administrative corruption and “financial leakages”,

overloaded courts, indeterminate dispute resolution, limited protection

for the vulnerable, an ineffective implementation of policy and laws and

ultimately social unrest.

Cost-effective, accessible and reliable service delivery by land

institutions is an important attribute to an overall measure of

governance in land administration. Service delivery, most often provided

by a government institution, should also be widely used by the public

and other institutions. Broad participation in services represents

equity of access regardless of authority, wealth, location, ethnicity or

gender. The impact of poor governance within a land administration

institution is often reflected in poor service delivery. Issues include

user uncertainty, a lack of public trust and participation, slow service

delivery, high and uncertain costs and an unsustainable system. The

overall process of service delivery should be seen as business rather

than bureaucratic processes. Streamlining of process flows is an

essential part of achieving efficiency. Computerization may be a means

to doing this, but more readily, this should be undertaken as a

complementary tool.

A large part of effective service delivery is good records

management. This is essential for maintaining the integrity of secure

tenure through property rights registration. Record data should be

simple and unambiguous. The actual records should be easily identifiable

and retrievable. Dealings with records need to be undertaken according

to a set of standard procedures that are set out in operational manuals.

A comprehensive set of procedures should include variations to

procedures caused by technology, levels of authority and the location of

services.

The system should be readily accessible to those registering

dealings, considering costs as well as information and procedural

requirements. A cost structure needs to be applied that is not an undue

barrier to participation. Physical access often requires some level of

service to be decentralized. Options of one-stop-shops,

private-public-partnerships for front office services, local lodgement

points and mobile services are different strategies that offer services

close to the public. Registration procedures need to be clearly

understood by the general public without the unnecessary involvement of

external professional service providers.

System sustainability relies on a guarantee of financing to maintain

services and operations. This may be achieved through external

government budget allocations or self funding structures. Institutions

aiming for the latter financing strategy typically demand a reform of

the system that addresses inefficiencies and the effectiveness of

service delivery. Involving the private sector in service delivery is

one approach possible where contracts are well designed and managed.

Capacity building options within the government sector should

emphasize efficiency improvements and quality and these strategies

should not be limited to technical procedures but involve management

resources also.

Objective 5 –Land Administration information is reliable and

accessible

Information leads to empowerment. Empowerment means that people can

make informed decisions, they have knowledge and capacity to

participate, and are able to question decisions which may affect them.

This is particularly relevant to the poor who often lack vital

information, communication mechanisms and visibility to voice their

concerns (UNDP 2003). Broad access to information is also critical for

policy making. Public dialogue and disclosure of information between

government sectors is important. Increased access, information sharing

and dialogue assists policy development to ensure policies reflect the

needs of the people.

Similar to the effects of weak governance on service delivery, issues

arising from a lack of information include public distrust, lack of

oversight, poor data management, and under-utilized data for decision

making in both government and private sectors. Quality and reliability

of data in the public arena requires a level of control in the

maintenance and dissemination of data. Therefore roles, responsibilities

and obligations of data custodians of information should be clear in

both the public and private sectors. An industry model to set data

security and cost structures between ‘free’ versus ‘fee’ public

information, and access and dissemination policies for onward use of the

data should be considered at high level.

Broad access to information is an empowering and participatory

mechanism for a land administration system operating under conditions of

good governance. Strategies for ensuring accessible information are

overcome in theory once there is general consensus by government at a

high level that public records should be made available upon request.

Once a positive decision on access is made by a government that balances

privacy, security and public access concerns, access strategies can be

readily put in place. Practical obstructions to access information are

acknowledged as an issue in many countries particularly where there has

been a long period of poor record management. Access to any public

information should be up-to-date, unambiguous, and reliable.

Computerization strategies are very useful for supporting public

information access policies as they can significantly improve storage,

access, retrieval and sharing of data, both spatial and textual.

Computerization is also essential for web based access. Ensuring

adequate resources are available to support computerization and ongoing

maintenance is critical. This also requires systems be in place to

integrate decentralized operations whether they are manual or automated.

The cost of this reform strategy should ensure that those costs passed

on to the consumer are not overly onerous. Accessible and easily

adaptable information will increase demand for its use in decision

making. As with first registration, during the early stages of

computerization and publicly accessible data, costs should be minimized

to encourage participation and increase demand for the formal system and

services provided.

Objective 6 – Transparent Public Land Management Processes

Generally, public land and other public assets are badly managed

throughout the world. There is limited awareness of both the

consequences of weak governance in public land management and how to

improve the situation. Public land is often treated as a “free good”,

whereas “good” land in terms of location, use and service delivery is in

fact scarce and valuable. State land allocations are often not

undertaken transparently. The state may be stripped of its assets

through “land-grabbing”, i.e. the transfer of state land into private

hands through questionable, if not illegal, means. Illegal land

exchanges usually leave special interest groups favoured in land and

other natural resource concessions. There may be political interference

in management decisions, and compulsory purchase may be used

inappropriately to further private interests.

The possible impact of illicit misappropriation of state assets on

development processes and poverty eradication is enormous. It has both

direct and indirect negative impacts on development. Economic and social

impacts, including social unrest and disputes are widespread due to

illegal allocations, disposal and use of public land.

Public land management is a critical factor for ensuring good

governance in the administration of land in a country. There are common

factors involved in poor public land management. There is typically

ambiguity in authoritative roles and responsibilities, a lack of

accountability or methodology in the systems of allocation,

appropriation, disposal or use of public land, and a lack of information

on state assets. Weak governance in this area has direct and indirect

implications for citizens, and broader effects on economic development,

political legitimacy, peace and security and development cooperation.

There are a number of elements that can be applied to a strategy for

developing good governance in this area. These elements are applicable

to any country situation or stage of development. While the following

strategies have good intentions, reform is difficult as key stakeholders

in the equation often have vested interest in keeping the status quo.

Therefore, these suggestions are best applied in parallel within a

whole-of-government “good governance” strategy.

Objective 7 –Property Valuation serves the market need and

taxation is clear and efficient in support of policy

Property valuation and taxation has important implications for

governance in land administration. Land resources in all societies are

finite and a fundamental basis for social and economic development. An

equitable, fair and easily understood taxation system is more likely to

have willing participants, than an unclear and non-transparent system.

Poor systems for property valuation and taxation can be an indication

of poor governance in land administration. These lead to uncertainty in

market prices, difficulties in valuing property, constrained land

markets, increased land disputes and appeals, loss of revenue and

inequitable property tax burdens.

Valuation procedures provide the framework for statutory valuation

purposes and should be transparent and fair. Different methods for

valuing property depend on the sophistication of the property market. A

standardized method should nonetheless be chosen that covers all

property. Valuation information or sale values should be made publicly

available to improve transparency in the property market. These elements

are necessary to remove the common practice of under-declared values

associated with high property transfer fees and taxation rates.

Objective 8 – Judicial and non-judicial institutions are

accessible to resolve disputes

Land administration systems should aim to assist the resolution of

disputes over land. Mechanisms to resolve disputes may be available

through the judicial system or alternative administrative systems. These

mechanisms must be accessible, unbiased and efficient in resolving

disputes for all citizens. During initial adjudication of property

rights, local level adjudication teams that work directly in the village

with local authority is an effective strategy for resolving minor

boundary or rights disputes to advance formal registration. Strategies

for dispute resolution must be culturally sensitive and guidelines

should be prepared to assist mediations that encounter conflicting

issues between customary and statutory laws.

5. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

This paper presented the current approach taken in attempting to

translate governance into the land domain. Drafting a Conceptual

Framework will create an investigation platform for governance in land

administration. This framework can then be integrated in various country

contexts to help in the identification of structural deficiencies that

lead to unsatisfactory performance in the land domain. This can be used

to devise more complementary policies to ensure positive outcomes within

the land administration domain.

The draft Conceptual Framework has undergone rigorous consultative

process with a range of land administration experts. In the main draft

Conceptual Framework document, of approximately 180 pages, each of the

eight objectives are comprehensively illustrated using current practices

and project examples, largely from World Bank experience. The eight

objectives and study approach highlight the key themes and sub-themes

and how these themes are interpreted in terms of the implications where

governance is lacking. The scope largely interacts with fair policies,

legitimate rights, participatory land management, transparent

institutional functioning, especially in terms of public land

management, information access, clear and efficient land valuation and

taxation and equitable dispute resolution procedures.

Continuing with the development of this draft Conceptual Framework

requires further economic analysis. Following this, the next phase will

concentrate on developing a final set of indicators and a rigorous

methodology to conduct country case studies which assess governance in

land administration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is based on preliminary findings from a broader study on

land sector governance by the World Bank’s Agriculture and Rural

Development Department, with support from FAO, UN-Habitat, and other

development partners. The views expressed here are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent those of the World Bank, its Executive

Directors, the countries they represent, or of any of the supporting

institutions. The authors appreciate the comments and advice of the Bank

team as well as other members of the project advisory committee, case

study authors, and comments from the public during the e-conference. A

number of authors are contributing to the development of the Conceptual

Framework and there experiences and wisdom are greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

Burns, T., 2007. Land Administration Reform: Indicators of Success

and Future Challenges, Agriculture and Rural Development, Discussion

Paper 37, World Bank.

Dobriansky, P., 2003. Principle of Good Governance, Economic

Perspectives, March.

FAO, 2007. Good Governance in Land Tenure and Administration: Land

Tenure Studies 9, Rome, FAO.

Grindle, M. S., 2007. "Good Enough Governance Revisited." Development

Policy Review 25(5): 553-574.

McAuslan, P., 2002. “Tenure and the Law.” In Land, Rights and

Innovation: Improving Tenure Security for the Urban Poor, ed G. Payne.

London: ITDG Publishing.

UNDP, 2003. Access to Information, UNDP Practice Note, prepared for

UNDP.

UNESCAP, -. What is Good Governance?, Poverty Reduction Section,

Bangkok.

UNHABITAT, 2004. Urban Governance Index: Conceptual Foundation and

Field Test Report, August.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Tony Burns

As founding and Managing Director for Land Equity International, Mr

Burns has over ten years involvement at management levels on

multilateral financed land administration, tilting and policy projects.

He is the Team Leader for the Governance in Land Administration study

(Oct 2007-Nov 2008). He has over 20 years experience in land management

and natural resource projects covering the full project cycle, and is an

expert in project design, land policy review, evaluation of cadastral

survey and mapping procedures, land titling, land administration and

spatial information systems. Mr Burns also has interest and experience

in management of change, performance auditing and assessment of project

implementation against objectives and milestones. Mr Burns recently

authored a World Bank, Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion

Paper on “Land Administration Reform: Indicators of Success and Future

Challenges”.

Kate Dalrymple

Kate is a Senior Land Consultant at Land Equity International

currently working on assignment in Lao PDR on the Laos Land Titling

Project Phase 2. Kate also provides technical support and assistance to

the Managing Director and team leaders contributing to the research

dialogue and development of land administration strategies and policy.

CONTACTS

Dr. Kate Dalrymple

Land Equity International

PO Box 798

Wollongong 2520

AUSTRALIA

Tel. + 612 4227 6680

Fax + 612 4228 9944

Email:

kdalrymple@landequity.com.au

Web site: www.landequity.com.au

|