Article of the Month -

September 2003

|

Spatial Information for

Sustainable Resource Management

Gerhard Muggenhuber, Chair of FIG Commission 3 - Spatial Information

Management, Austria

This article in

PDF-format.

This article in

PDF-format.

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Indices for Characterizing a Society

3. State of the Art of Spatial Information Management

4. How Society can Benefit from Spatial Information

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

6. Literature

This paper promotes the involvement of spatial information as an important

contribution to decision making as an integrated process within a

multidisciplinary network. Geoinformation (GI) is not any more a single

tool of a small community of Surveyors and Geographers focusing on

Spatial Information Management. GI has crossed the gap between

individuals and enterprises, but there are still some shortcomings in

using spatial information.

In the first part of the paper objectives of information management as a

contribution to sustainable development will be reviewed and the indices

for characterizing resources of a society will be identified. In a second

step the state of the art Spatial Information Management will be described

by examples. Finally the paper focuses on the impact on and benefit for

society and the surveying professions of increased use of spatial

information.

2. Indices for Characterizing

a Society

Usually people in a society are not aware of slow spatial changes over a

longer period of time and thus tools for managing spatial and temporal

information are needed. But how can those relevant spatial components be

defined and how can they be used to optimize the use of resources by a

society?

Traditional mechanism for optimizing resources may help to understand

potentials for optimizing the benefit for a society using temporal

information. A society as a compound of interrelated individuals agrees –

driven by traditional concepts - on value systems and the use of resources

to achieve defined aims for the majority of individuals. In general the

use of the various resources is first of all a decision of the society

dependent on its value system. Spatial information and GI tools are

suitable means to optimise the sustainable use of resources within a given

framework. Societies with various and diverse value systems are

unavoidable under higher social pressure. An example (Thurston, 2003) may

clarify this: It is an unspoken rewarding system in the western society

that (i) headwork is better rewarded than handwork; (ii) financial skills

are better rewarded than technical competences; (iii) management talents

are better rewarded than financial skills. Those societies with a

rewarding system in conformity with their main sources of wealth and

prosperity have a tool for optimizing their resources which also serve as

a shield against poverty. There are obviously mechanisms which facilitate

the optimizing processes in a society to improve an infrastructure.

2.1. Framework for Optimized Infrastructure

Can we derive from the general decision making mechanisms of a society the

processes for improved use of resources related to spatial infrastructure?

The general public is not much interested in technical issues and the

consequences of decision making seem be clouded in mystery.

In his book “The Mystery of

Capital - why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere

else" De Soto [de Soto, 2000] surprises with the empirically grounded

argument that "most of the poor already possess the assets they need to

make a success of capitalism. What they lack is the ability to turn their

assets into usable, mortgageable, multipliable capital…. In the West every

parcel of land, every building is represented in a property document that

is the visible sign of a vast hidden process that connects all

these assets to the rest of the economy…. The vast hidden process is the

western, legalized property system… this system is clouded in

mystery, a mystery to people in both the West and the rest of the world.”

Actually, there are some mysteries that De Soto brings to light. The first

mystery is the "lack of information." The poorest people in the

Third World do not know that they are sitting on valuable material assets.

Secondly the "mystery of capital" itself: Capitalism is what a

legal, property/contract system allows people to create values based on

their material assets. The third mystery is the lack of "political

awareness" of changes: In recent decades, people all over the world

moved to cities - a migration with implications of revolutionary

proportions that have been virtually ignored. The fourth is the “mystery

of forgetfulness” - the "missing lessons learned from history." People

in rich countries don’t even recall how their legalized property system

came into existence. Finally, the "mystery of legal failure"— why

property law does not work everywhere: Third World Countries cannot just

transfer the western legal system without linking it to their own

traditions of values. Doing so is an obstacle for creating values out of

assets.

2.2. Categories of Infrastructure

From the above-mentioned observations we can derive a list of resources

contributing to development of a society’s infrastructure. Most of these

infrastructures have a spatial component. In the following some of that

infrastructure is discussed:

-

Human resources: people contribute with handwork or headwork

-

Natural resources – these are the main resources of an agricultural or

industrial society

-

Infrastructure is a resource developed by a society over time -

infrastructures for transportation and power supply, but also

telecommunication and Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI):

-

Information systems with applications like mapping, land register &

cadastre

-

Political framework, governmental systems

-

Legal framework

-

Administrative systems

-

Transport system

-

Communication network

-

Networks providing goods and service (stores)

-

Security System (internal/police & external/army)

-

Health System

2.3. Human and natural resources

Human and natural resources are usually finite. Sustainable

development provides a framework under which communities can use

available resources efficiently, create efficient infrastructures, protect

and enhance quality of life, and create new businesses to strengthen their

economies.

2.3.1 Human Resource for Geoinformatics

In the field of Geoinformatics training currently several policy

initiatives transcend current education strategies. New job description

will come up with specifications like: Spatial Information Officer,

Information Cartographer, Metadata Specialist (Thurston, 2003).

Surveying appears to have lower public esteem than Geoinformatics.

“I'd like to think training needs are being driven by the marketplace,"

says Kelly, Managing director of ANZLIC.

|

Networks of universities like

UNIGIS provide a service as a global, virtual & multilingual

university for Geosciences, also working together in research and

curriculum development activities related to GIS education. Students

registered in a UNIGIS programme may qualify for the EuroMasterGI, a

European post-graduate qualification in Geographic Information. On the

other side there is simply a lack of interest amongst the student

community in surveying careers. |

Information technology has to take care of the customers as human

resources and as partners in business processes. What are the challenges

for the customers? The customers get more and more involved in the

unpleasant aspects of merging, transforming, overlaying and filtering

information. The Director of the Open Planning Project in New York, Rob

Hranac, (published in [Corbley, 2002]) commented: “GIS users spend

90% of their time searching for datasets and 10% actually using them. Can

you imagine how the industry would grow if those numbers were revised?”

A sound information infrastructure needs more than data. There is urgent

demand for harmonization of services and data for optimised common

use. There is no direct contact any more among creator, provider and user

of spatial data. Therefore data need not only standardized geo-referencing

in order to provide a clear link to administrative units, addresses or

other specific geographic units. There is an increasing demand for

metadata on spatial information. Librarians have been producing and

standardizing metadata for centuries. The spatial information managers

have to do the same for easier access to all the spatial information

created.

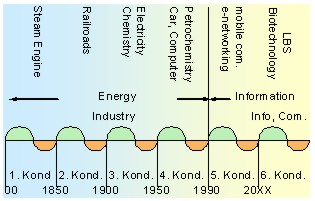

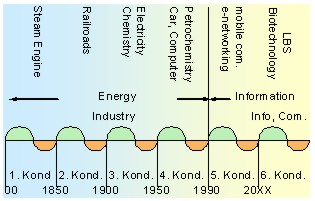

2.4. Information as a Driving Force

The driving force behind economic development depends on the focus of a

society. In Europe the transformation from an industrial to an

information society became obvious during the recent thirty years. The

industrial society needed access to steel and coal - both together

were forming the bases for industrial development. The

European Coal

and Steel Community (ECSC) of 1952 was an essential root of the European

Union and expressing herewith the industrial background. Nowadays in our

information society people are often not yet aware of the new demands on

infrastructure, when changing their main source of income from producing

industrial goods to a service oriented “knowledge economy” based on

information and communication technology (ICT).

Data and ICT are the driving forces behind an information society. So it

doesn’t surprise that at the end of the 20th century the focus was on

digitising data and on building infrastructures for accessing these data.

The next wave might come from integrated services as driving force behind

our society. According to the Kondratieff Cycle (Nefiodoff,

2001 and

Alexander, 2002) the next wave will focus on the ability to cooperate,

which seems to become the key qualification for increasing productivity.

This means: Information becomes interrelated.

|

The Kondratieff Cycle is a theory based on a study of

nineteenth century price behaviour in the US. Kondratieff observed

certain characteristics about the growth and contradictory phase within

long-term periods (which averages 54 years in length). It can be

concluded that there is a systematic structure behind periodically

behaviour of economy. |

2.4.1. Information for Decision Making

Good decisions are based on good information. Good information is

based on good data. Planning, shaping and modelling of proposed plans

are parts of information management which became a fully digital process.

The demand for spatial information for decision-making can be considered

from different perspectives. First and foremost, the process of

decision-making requires information as an input (informed decisions).

Secondly spatial information is needed for impact analysis. As is well

known, decisions have a range of immediate up to long term impacts. In all

cases, the consequences of decisions must be predicted and controlled.

Especially development processes require monitoring and evaluation of the

decision’s outcome. This is the reason why the increased need for spatial

information is becoming a challenge for people who are involved in decision

making with spatial components.

Data collection and data analysis have contributed to an improved

understanding of social and environmental impacts on planning and

development actions. With new surveying, communication and information

technologies decision-makers have more spatial information and thus

accountability on the interrelationship of communities, impacts and effects

of decisions. Finally the decision-makers have a powerful instrument for

future developments.

2.4.2. Information as Part of an Infrastructure

It is not just about the availability of information but we also need

links as a bridge from existing knowledge to new information. Information

exchange as a process enables humans to share and acquire knowledge from

others. Information technologies (IT), developed to support information

processes, are still designed to operate within established structures of

closed systems. In order to overcome the barriers of closed

communication cycles and to grant wider access to knowledge, it is not

sufficient to deliver data. There is a demand for information entities

containing indicators for potential common interests, values, interpretation

patterns including rules for intended goals. New knowledge can only be

achieved when incoming information can be linked to existing knowledge.

Therefore a different view on information results in a different knowledge,

which also depends on existing knowledge. Spatial Information services have

to consider the users perception.

2.4.3. The Value of Information

In business world surrogates are often used because we have no access to

the original. The ownership title is such a wildcard. Information as a

wildcard allows us to model a “virtual world” for orientation and

decision-making. Thus information allows a remote observation of space and

time in a way we could not do otherwise – like environmental scenarios.

What kind of information infrastructure is needed to let these mechanisms

work? The recent introduction of the Euro increased the awareness for the

demand of integration of individual, fragmented markets into a joint

European one. Some of the lessons learnt may also be helpful in a

knowledge-based economy for introducing information as a surrogate (of given

values) for facts proved or collected. This applies for the land market

and the ensured information on property in the same way as for spatial

information in general.

2.4.4. Political System as Framework for Sustainability

In most countries, the idea is that the government will tell you what is

good for you. However sustainable development can only be achieved by

creating trust in the approach of a society in general. Participatory

democracy, decentralisation and community empowerment can support such a

sustainable development in a society. The practice according to

Ian Bremmer

from the consulting business is still that development is linked to

individual politicians rather than with the whole society: “Investors are

starting to understand that economic reform depends on the politicians

promoting it, remaining in power.”

Decisions are made at different administrative or organisational levels.

Nowadays, there is a global tendency to decentralize decision-making

and delegate responsibility to regional or local authorities or

organizational units. As a result, the number of points where decisions are

made has been increasing and this leads, among other things, to a greater

need to share geoinformation.

Modern governance requires transparency and the involvement of

communities and citizens in the decision making process. Decentralisation

and community empowerment are strategies to achieve transparency and

participatory democracy. This also applies for community based land

management processes in particular and development administration in

general. Modern spatial information management tools facilitate

decentralisation, community empowerment, and citizen participation, which

guarantee social cohesion and sense of belongingness.

2.4.5. Legal and Administrative System

The legal system, especially the property laws of a country reflect the

rather sustainable concept in people’s minds. In Europe most of the land

administration systems were created for tax purposes and have their roots in

an agricultural society.

The legal system has an essential impact on the use of spatial

information:

- a sustainable land market is based on secured Property Rights and

access to relevant public information for Government and citizens,

- a legal framework established to secure the Intellectual Property

Rights are an essential component of an information market. Market

distortions deriving from a high percentage of misuses – like in music and

software industry - would have a negative impact on use and trust in

spatial information.

- Data Protection legislation protects individuals against abuse

of information based on an understanding of the national security issues,

but has an impact on access to information.

|

The Bathurst

Declaration on Land Administration for Sustainable Development

(Bathurst, 1999) calls for a commitment to provide effective legal

security of tenure and access to property. It identifies the need for

the promotion of institutional reforms to facilitate sustainable

development and for investing in the necessary land administration

infrastructure. It recommends the active participation by local

communities in formulating and implementing the reforms, and it sees an

increasingly important role for IT in developing the necessary

infrastructure and in providing effective citizen access to it. |

2.4.6. Land as a Multipurpose Resource

The market value of land is no longer derived from agricultural benefit,

but increasingly interesting for industrial use, for urbanization and as a

resource for transport systems. All of them offer higher prices than the

agricultural land market. The land market became distorted – rules for use

(land use planning) have been developed. Even in a post industrial society

real property rights are one of the cornerstones for the land market - a

driving force for economic development based on four pillars.

|

Figure: Four pillar-model of the Land Market - based

on three pillar model of (Dale, 1999). |

2.4.7. Rural Resources for Urban Development

There is a global trend of migration from rural to urban areas because

urban environment seems to offer better jobs, income and infrastructure. The

urban-rural conflict becomes visible in the slums and suburbs. More and more

rural resources are used for urbanization: human resources as well as land

are used for urban development. Human resources become a main part of urban

economy. On one side the “brain-drain” is a hindrance for rural development

– on the other side the rural regions serve as buffer for economic

fluctuation as long as there is a rural infrastructure to which people can

come back.

The United Nations estimate that by 2025 54% of the world’s 7.8 billion

population will be living in urban areas. The percentage is higher in the

developing countries which also results in a breakdown of the transport

system. “We have to change the way we move ourselves if we are to avoid

the gridlock of environmental degradation brought out by transport” said

Kurt Hoffman, director of the London-based Shell Foundation.

Statistical data point out rural areas as multidimensional reserves

for human resources that are needed for urban development. Human

resources and human knowledge are some of the most important resources

for sustainable development all over the globe but especially in

high-industrialised countries. The globalisation of economy and the

complexity of global ecology need experts. The high-industrialised countries

have met this need within the last decades and consulting services,

education and training became substantial export articles to developing

countries.

2.5. Land and Water Resources

Land serves as living environment and as a base to fulfil the various

human needs with three main functions (Banko

& Mansberger, 2001): (i) economic, (ii) social and (iii) ecological

functions, whereas the priority setting of functions characterises a

society.

2.5.1. Land as Economic Resource

Beside capital and labour land is one of the classical production factors

of an economy. It can be seen as a product itself or as a mean for producing

other goods. The land market has some specifics: Firstly, the supply of land

is constant within a region. The concept of the free-market system that

supply of goods (land) can be increased works only for some branches of the

land market - e.g. the supply of building land can be increased by

modification of zoning. Secondly, land is not a homogeneous product: Parcels

differ e.g. in regional sites, in the degree of existing infrastructure, in

soil quality. So each parcel is not fully substitutable. Land and water are

a basic necessity for the food industry, for energy resources (e.g. oil,

coal, water) and for the cultivation of renewable resources (e.g. wood).

2.5.2. Land as Social Resource

All non-economic benefits for human beings from land can be summarized as

social resources of land. These aspects include the function of land to

regulate the climate and the water supply as well as the purification of air

and water.

Land often has an emotional component for its residents. The

region of birth often is seen as homeland. Many military conflicts were

justified by claims for the same region by different nations. But land also

is an inspiration medium for artists. The beauty or the specific landscape

of a region often are the catalyst for the composition of paintings, poems

or music.

The function to reduce noise emissions becomes increasing

important in densely populated areas or areas with a high rate of traffic.

Considering the protective function for human beings, land plays a

schizophrenic role: Besides of the climate conditions, the specific

topography of land is the reason for most natural disasters, e.g.

avalanches, floods or landslides. On the other hand land can protect people

from natural risks – once again due to its specific topography. Thus

information about land becomes an important part of modelling and

planning within the frame of disaster risk management. The following

example clarifies the potential role of spatial information within

disaster risk management: The Government of India and UNDP started a

joint Natural

Disaster Risk Management Programme under which a database for disaster

risk management and sustainable recovery is built.

2.5.3. Land as Ecological Resource

The ecological function of land in terms of climatic change and

conservation of natural resources and biodiversity has received increasing

attention by the international community (UN 1992; UNFCCC 1992, 1998).

International agreements address the requirements for the functioning of

ecosystems. As a consequence of that many worldwide and national initiatives

focus on awareness of biological and diversity issues. Landscape is

recognised as a unique mosaic of biotic and abiotic features (for example:

cultural, natural or geomorphologic features). It is recognised that the

change in land use practices is important factors for both biodiversity

and diversity of landscapes, which again asks for modelling tools of

spatial information.

3. State of the Art of Spatial Information Management

3.1. Thirty Years of Spatial Information

Looking back at the history of Spatial Information Management shows the

progress made and better explains the current challenges as well as next

steps to be taken.

Thirty years ago we learned about GIS. We focused on implementing and

tuning a stand-alone tool - a unique GIS-package adapted to the internal

needs of a company. We were happy to ride the horse and accepted frictions

caused in our production processes.

Twenty years ago we were focusing on digitizing data – everything had

to become digital. We stuffed our information into bits and bytes. Everybody

did it his own way, which turned out to be a hindrance for data exchange.

Ten years ago we realized that we did similar things and needed to

share data. We realized that frictions in sharing information are not only

caused by data, but also by institutional settings.

Nowadays we try to improve our institutional setting by cooperation –

some even by merging organizational unit, but there is always an additional

organization to cope with – so cooperation is needed anyway.

During these years our focus has been shifting from hardware and

software (“How to use GIS?’)

· to data acquisition (“From were to receive more data?”),

· to data quality (“Why all these different data do not fit?’),

· to data integration (“Why did you use a different reference model

?”) and

· to process integration (“How can multi-institutional cooperation

provide a better service?”)

As a result from that a lot of effort are necessary for standardization (ISO-TC211,

OGC and within all the GIS-companies,

GSDI,

EU-INSPIRE), but still there are frictions.

3.1.1. Cooperation Forced by Technical Improvements

Within the last decade a lot of changes have took place in the field of

data collection, data processing and equipment (GPS, laser-scanning, digital

imaging and image processing). The development was mainly technology

driven. Thirty years ago surveying equipment got an innovative push by

the computer technology. The competition on new technologies led to the

merging of companies and partnerships between companies. At the

beginning of this process companies of similar profiles merged (like Wild

and Kern). Later on companies of rather different backgrounds also merged.

Surveying equipment met software (Leica, Helava, System9). Nowadays

cooperation is seen under a wider perspective (e.g.

Partners of Leica) and goes beyond the approach to integrate software

into some hardware (surveying equipment).

It seems that the business models changed. The change from supply

to demand driven developments, products and services requires the

involvement of heterogeneous expertise. Therefore a flexible cooperation can

bring more benefit than just merging companies, which caused many frictions.

The next step of this business approach resulted in combining tools used in

that process e.g.: “Total Management Systems for Real Estate” with GIS

(e.g.:

SAP and

ESRI).

Technology empowered individuals and local communities to create

their own IT-solutions with integrated tools for spatial information

management. While the amount of digital spatial data collected at the local

government level is dramatically increasing, but little is incorporated in

the public domain. This development might still be rather an opportunity

than a threat. One day all these data can contribute to aggregated

information as a result of an integrated, well coordinated approach to

spatial information.

3.1.2. Cooperation Forced by Economic Pressure

In the past technical development of equipment resulted in a faster and

more cost-efficient data production. In the next step improvements focused

on optimised production processes within individual companies. In the

meantime organizational improvements can be obtained by streamlining

procedures as inter-institutional “Clustering” processes.

The increased financial pressure on public institutions as well as on the

private sector forced the process of rethinking their business models.

Duplication of work is not affordable any more. All kind of outsourcing

became fashionable e.g. acquisition and maintenance of spatial data.

Traditions were given up in favour of process oriented cooperation along the

chain of added value and led to clustering (www.giscluster.at).

Whatever can be provided by somebody else in a more efficient way is

preferable to in-house solutions. That situation calls for partnership and

teamwork across disciplinary lines, bridging different commercial sectors,

which is also an opportunity for local communities: “Paradoxically

the lasting competitive advantages of a global economy are increasingly

focusing on local conditions – knowledge, partnerships, motivation:

components which hardly can be reached by afar rivals” according to

[Porter, 1998].

3.2. Good Practice

There is a growing number of applications and services utilizing spatial

data to provide business solutions in government agencies, business

enterprises and the communities such as

emergency

management, disaster risk management,

natural

resource management,

land

administration,

environmental

monitoring,

health,

geo-marketing,

routing,

tourism and

finance.

Data policy, institutional framework, technology and standards are emerging

as the four major pillars of a spatial data infrastructure. The following

examples provide some overview of activities:

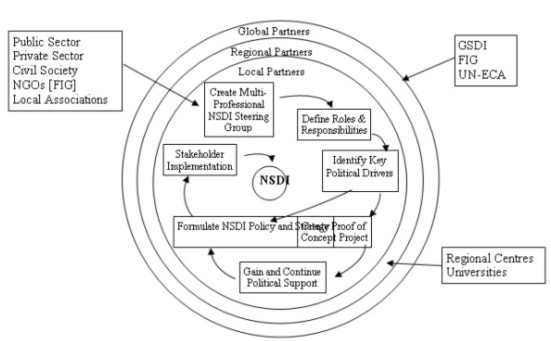

Fig.: Iterative process for achieving NSDI [FIG Publ.30]

3.2.1. Awareness of Spatial Information Policy

The Europe, Asia and the Pacific and America are actively involved in

coordinating the development of a Regional Spatial Data Infrastructure:

There are also attempts to establish a

National Spatial

Information Framework (NSIF) in Africa.

3.2.2. Standardized Spatial Information on Global Level

The global user community for spatial information standards consists of

nations, non-governmental organizations, such as the United Nations,

multilateral banks and international initiatives and programmes.

International Organizations facilitate the use of spatial information from

rather different angels. Improved solutions through standardizations,

development of integrated services and cooperation are supported by

organizations such as:

|

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) TC-211 aims at

establish a structured set of standards for information concerning

objects or phenomena that are directly or indirectly associated with a

location relative to the Earth.

OpenGIS Consortium (OGC) -

specifications support interoperable solutions with "geo-enabled"

web-tools and location-based services to make complex spatial

information and services accessible and useful for other applications.

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)

develops interoperable technologies to lead the Web to its full

potential. W3C is a forum for information, commerce and communication. |

3.2.3. Spatial Information Policy on Global Level

Many international organizations address the issue of spatial

information, acting as opinion leaders, policy makers as well as providers

of economic, environmental and financial data – all of them interrelated

through spatial information. Some interested links are given:

|

UN-HABITAT runs two major worldwide campaigns – the Global

Campaign on Urban Governance, and the Global Campaign for Secure

Tenure. UN-HABITAT is monitoring global trends and assesses the

progress of implementing the Habitat Agenda by two main instruments:

Global Urban

Observatory and Statistics and

Best Practice Database.

UN – FAO has launched special activities and programmes to mobilize

governments, international organizations and all sectors of civil

society in a coordinated campaign to eradicate hunger and to turn the

slogan “Food for All” into reality. FAO - publications related to

Spatial Information:

|

|

Two Wold Bank publications on resource management and spatial

information:

|

3.2.4. Spatial Information – Activities on Regional Level

Integrating tools for a joint information infrastructure is a long

process similar to the political decisions in Europe to establish an

integrated economy. The decision on a common currency was made in the

1950´ies and needed 50 years for implementation. The strategy decision on

telecom liberation showed good results within 10 years. Telecom and wireless

internet are tools needed to set up Tele-cartography and Location Based

Services. The increasing integration of the European economies led to an

increasing demand for pan-European information products. Activities for

geoinformation in Europe started with strategies, but focus more and more on

a practical approach:

|

The EU-INSPIRE Project is a

triggering force for a joint European action on spatial data

infrastructure in practice. A coordinated decentralized approach

should ensure a flexible solution based on information to be summarised

for implementing and monitoring policies of decision-making (regional,

national and community).

The EU-EULIS project within the

eContent-programme aims at establishing a European Land Information

Service by accessing national land information across borders via the

Internet. |

In 1999 the EC published a Green Paper on “Public

Sector Information”. In 2001 a “White Paper on Governance”

announced that all EU-legislation will be accessible for free on the

Internet in all the Union languages through the EUR-Lex portal. In 2001 the

EC has launched “eEurope

2002: Creating a EU Framework for the Exploitation of Public Sector

Information” which focuses on the economic aspects of public sector

information.

|

The right to re-use public sector information will support the

growth of the European Content Markets similar to the US where the

reuse of public sector information has given way to an information

market that is up to 5 times the size of the EU market (Spira-Study,

2000). Europe is seeking for a balance between initiating market growth

and charging for public sector information on the way to a knowledge

economy. The key factor for success seems to be the joint interest

of partners involved based on economic factors as driving force for

improved services. |

3.2.5. Spatial Information on National Level

|

The vision of the

Spatial Information

Council for Australia and New Zealand (ANZLIC) is that economic

growth, social and environmental interests are underpinned by spatially

referenced information. ANZLIC's facilitates easy and cost effective

access to spatial data and services provided by a wide range of

organisations in the public and private sectors. |

In the United States the

Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) is developing the National

Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) in cooperation with organizations from

State, local governments, the academic community, and the private sector.

The NSDI encompasses policies, standards, and procedures for organizations

to cooperatively produce and share geographic data. The goal of this

Infrastructure is to reduce duplication of effort among agencies, improve

quality and reduce costs related to geographic information.

In Canada

GeoConnections a national partnership initiative is working to build the

Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure (CGDI), which will make Canada's

geospatial databases, tools and services readily accessible on-line.

3.2.6. Cooperation on Spatial Information on Operational Level

- “The GeoData Alliance (www.geoall.net/)

is an innovative, non-profit organization open to all individuals and

institutions committed to foster processes to enable the creation,

effective flow, and beneficial use of geographic information.

- In Austria the GIScluster (www.giscluster.at)

is a fusion of companies that offer a broad selection of know-how and

services along the chain of added value. This interdisciplinary

cooperation within the business of ‘spatial data management’ includes

acquisition, management and the visualisation of data.

- The ‘Three Ordnance Surveys’ of Great Britain, Ireland and

Northern Ireland cooperate on building and maintaining national databases

[Murray et al., 2001]. They intend in the long run standardisation of

data, structures, identifiers and formats.

- The Austrian software company Progis (www.progis.com)

is applying new approaches to ‘Precise Agriculture’. Their

decentralized approach of shaping the business procedures supports the

dataflow between farmers and the regional agricultural administration

centers to be used also for updating. Updating has to involve the farmer,

who knows about the actual changes in the field.

- An other good example for an integrated approach comes from Canada:

The “Land and Water

British Columbia Inc.” under the “Ministry of Sustainable Resource

Management” is responsible for land issues but also for

Water Licensing,

Water Use Planning,

Water Resource Information.

4.

How

Society can Benefit from Spatial Information

4.1. Benefit or Threat for Educational System

New tools and methods for learning came on the market during the last

years to support knowledge transfer and to enable virtual lecture rooms.

Will that change the whole educational systems? Can they substitute

traditional lecturing or replace the teachers? Questions that cannot be

answered yet, as the access to electronic media is the limiting factor for

this new technology at the moment: 50% of the population of North America

are able to surf in the Internet, whereas only approximately five percent

population have access to Internet. But there is no doubt that e-Learning

brings about new opportunities for knowledge transfer – also in terms of

life long learning.

The use of spatial information technologies is providing substantial

economic, legal and political advantages. Possession of spatial information

has also contributed to military power. We need to reflect on the

potential significance of technological and institutional changes for the

widening or lessening of social and economic gaps in society.

Traditionally intellectual and emotional engagement is attached to a

certain location. These place-based communities are increasingly being

complemented by virtual ones where people ‘meet’ and become involved with

others without regard to distances. The risk that Internet accelerates the

detachment of individuals from the places within which social networks are

formed is balanced with the opportunity to interact with self-defined

communities electronically in response to exclusion from local communities.

As people transfer more of their time and loyalty from actual to virtual

communities, the balance between place-based and non-place based

communities is shifting, with potentially wide-ranging implications both

for places and communities, and for the influence of place on individuals

(Goodchild et al., 1999, - Varenius-Project). This development might be a

disadvantage for the communities in rural areas.

4.2. Knowledge is Information in Action

The question is about combining multi-source spatial data with

processes into usable information products. It is all about

maximising the economic, social and environmental benefits from

investment already having been made in spatially referenced information. The

realisation is based on at least three components: data, processes and

knowledge. Progress has been made to improve the procedures of spatial data

acquisition, but the real challenge is the workflow:

- to organise business processes that support the availability

of, and accessibility to geo-information in the right place, at the right

time and for the right person;

- to create and maintain data models and databases from which

information can be extracted, processed and shared by many stakeholders at

any given time.

How can we deliver the right information to the right people at the right

time, if the right information must be derived from here-and-now parameters

that change daily? The answer comes from business model innovation. In other

words: the result of human activities on different locations is an

integral part of information required and should be considered as part of

our modelling processes.

4.3. Changing Role for Surveying Profession

Finally the role of the surveyors will not stay untouched by the modern

information management including data acquisition methods and distribution

technologies for streamlining inter-organizational workflows. Surveyors have

to develop from pure data collectors to information managers.

In the past dramatical changes in our geodata business derived mainly

from technological innovations. In the meantime however changes are more and

more caused by improved business processes with a sever impact on our

surveying business. Some of our customers and even some partners like

National Mapping Agencies started innovative reorganization processes, which

had some drawbacks:

- Reorganization takes time and resources – during that time customer

contacts are weakened.

- The renewed organization may again not fit because the business world

is changing constantly.

Even running the traditional “change script” faster does not work.

The reaction to increased business pressure with organizational changes

often is the wrong way. The most dynamic firms shift business models

without organizational changes. Instead of shifting organizational blocks we

have to shift mindsets!!!!

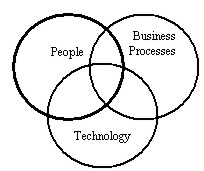

|

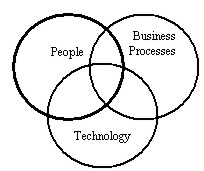

Fig. Integration of processes.

|

Some decades ago the strong position of surveyors with almost a

monopoly in geometric data acquisition was mainly based on

technology and people - technological innovation combined with highly

skilled experts. In the meantime technology became cheaper and easier in

its use. This led to a wider user community: thematic experts acquire

geodata themselves. This trend was increased by another change: Geodata

became more detailed in their “thematic resolution”. The required

knowledge for geodata assessment shifted from geometric to thematic

issues with the consequence that thematic experts are more involved in

data acquisition than surveying experts. |

But nevertheless surveyors are needed more than ever. The merging of

global geodata requires well-based knowledge about coordinate systems and

map projections. In the future four additional main activities have to be

realized by professional surveyors in the field of “Spatial Data

Management”:

- Coordinator of the workflow for geodata sets

- Information Manager (including documentation: metadata)

- Quality Manager (QM) for geodata

- Expert for integrating business data, thematic data and geodata across

different professions to generate “geoinformation for decision making”.

Or with other words: the surveyors have to mutate from “Geodata

Collectors” to “Managers in Geodata Clusters”. The training and

communication of these skills and the understanding of demands and language

of other professions will be essential for the success as a surveyor.

Surveyors, who contribute to the consulting business, experience already

today the wide range of skills and inter-professional cooperation needed.

The interval for launching new products will increase and business models

have to be adapted to the faster and more automated sampling of geodata. The

trend to lower costs for surveying and data capturing will continue.

Due to the broad thematic orientation and huge amount of geodata needed

for a wide spread field of users the organisation of data acquisition

requires new strategies. Co-operations and partnerships of companies and/or

institutions on a local or regional level (Public/Private Partnerships) in

so-called “Geodata Clusters” could be the key development. “Geodata

Clusters” will need a core group for the managing of geodata: Surveyors with

their education and knowledge of geodata management have to take this

position: Providing service for our customers and bridging contributions

from different professions. From that point of view I wonder how long it

will take national surveying associations to open up their communication

to other professions e.g. by organizing cooperations for developing a

better service to the customers.

There is a strong need for Spatial Information for public and

private decision-making

Decision-making for improved use of limited resources is highly related

to spatial information. Especially the basics of geoinformation (links

between men and land) should be maintained countrywide to enable and

guarantee unobstructed common and personal welfare.

Good Governance requires affordable integrated solutions for

access and use of geodata for an increasing number of users.

New Technologies opens opportunities to acquire more and detailed data

in a shorter time and enables real time access to geoinformation for a

nearly unlimited number of users. Within the last years powerful tools for

the storing and processing of geodata appeared on the market. However new

systems are still not affordable for local governments and communities in

many countries. Policies and strategies are necessary to make new

information and communication technologies accessible to poor people too.

Decentralisation and Community Empowerment require Spatial

Information Experts at local level.

The use of geoinformation resources requires knowledge at a local

level about data acquisition, data processing, and the visualisation

of data. The degree of geoinformation expertise is varying and depending

on the responsibility of a specific person or user group.

Decision-makers need another education and training programs in

information technology than people involved in the implementation or

maintenance of IT systems or specialists for data capture. Policy has to

focus its activities on capacity building in the broad field of

geoinformation technology.

Sustainable development requires information exchange between

different levels of public and private institutions.

The use of clearly defined standards facilitates the sharing and

exchange of geoinformation amongst various user groups. But the increasing

number of collected and available geodata also requires a detailed

description of the data, the so-called metadata. Metadata in the context

of SDI facilitates access to data and can also prevent duplications that

may arise from limited knowledge of available data residing at different

locations.

Implementation of spatial data infrastructure requires cooperation

between the private and the public sector and amongst all professions

involved in land management.

Land registers and land cadastres as part of SDI mostly are the

responsibility of public authorities. But decision-making processes demand

additional thematic information about land collected and maintained by

various public or private institutions or by professionals trained in a

particular trade. Partnership and cooperation among all groups is

necessary for successful geoinformation management.

Spatial Information is an essential part of the infrastructure

in a country.

The acquisition and maintenance of geoinformation itself seldom is a

cost-covering activity in a country. But the availability of

geoinformation has positive impact on public as well as private business

and welfare with consequences for the national economy. The creation of a

countrywide SDI must be a primary objective at all levels of

administration.

Decentralisation and Community Empowerment require a specific

geodata policy.

As shown above various private or public users on different levels of

administration require spatial information for decision-making – often

based on the same geodata. The number of units involved with geodata

management is increasing with the degree of decentralization. To avoid

redundancies and inconsistencies in the collection, storage, maintenance

and the distribution of geoinformation, policy has to provide the legal

and the administrative framework as well as the business environment

to clarify the responsibilities of various actors involved in geodata

management. The regulations have to include detailed specifications in

terms of the tasks for the units, in terms of the topics of data, and the

defined working areas. Geodata policy also has to coordinate strategies

for the integration of procedures within spatial information management.

Alexander M. (2002):

The

Kondratiev Cycle: A generational interpretation. ISBN: 0595-21711-7,

Published by iUniverse.com, 2002.

Badhurst (1999):

The

Bathurst Declaration on Land Administration for Sustainable Development.

Published by The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG). ISBN:

87-90907-01-9, Dec 1999, Frederiksberg, Denmark.

Banko G., Mansberger R. (2001):

Assessment of "Non-Monetary Values of Land" for Natural Resources Management

Using Spatial Indicators. In: Njuguna, H., Ryttersgaard, J. (Eds.):

Proc., International Conference on Spatial Information for Sustainable

Development, Nairobi, Kenya, 2-5 October 2001; FIG Commission 3, 310-322.

Corbley, K.P. (2002):

The GeoData

Alliance: A New Hope. Reprint from GEOWorld July 2002., (2002).

Dale P. (1999):

Is technology a blessing or a curse in land administration?. UN-FIG

Conference on Land Tenure and Cadastral Infrastructure for Sustainable

Development, Melbourne, Australia, Oct. 1999.

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 30:

The

Nairobi statement on spatial information for sustainable development.

FIG in co-operation with the United Nations, ISBN: 87-90907-19-1

Frederiksberg, Denmark 2002.

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 31:

Land

Information Management for Sustainable Development of Cities - Best

Practice Guidelines in City-wide Land Information Management. FIG in

co-operation with the UN-HABITAT, ISBN: 87-90907-21-3, Frederiksberg,

Denmark 2002.

Goodchild, et al. (1999):

Introduction to the Varenius-Project, International Journal of

Geographic Information Science, 13(8): 732-745, 1999.

Mansberger, R. (2003):

Geoinformation in Support of Decentralisation and Community Empowerment.

Proceedings of the Third Meeting of the Committee on Development Information

(CODI). United Nations, Economic and Social Council - Economic Commission

for Africa. Document Nr. E/ECA/DISD/CODI.3/27. 10-16 May 2003. United

Nations Conference Centre, Addis Ababa.

Muggenhuber G. (2003):

Geoinformation in optimized Business Processes. FIG Working Week,

Paris, 2003.

Murray, K. (2002): Bray, C.: Better connected: the three Ordnance

Surveys improve georeferencing links. Proceeding of the AGI Conference

at GIS 2001. United Kingdom 2001.

Nebert, D.(2001):

The SDI

Cookbook, GSDI-Publication, 2001

Nefiodow L.A. (2001),

Der

sechste Kondratieff, ISBN: 3980514447, Oct.2001.

Porter, M.(1998):

Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.

Free Press, 592 pages, ISBN: 0-684-84146-0 (1998).

Study for the EC by Pira International on commercial exploitation of

public sector information, October 2000

Thurston J. (2003): The New

Geo-Jobs, a second look in the New Millenium. In:

geoinformatics.com, Vol.6/2003, ISSN 13870858.

World Bank (2002):

Land

Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction, ISBN: 0-8213-5071-4,

Washington 2002. |