Article of the Month -

February 2006

|

Ghana’s Land Administration Project (LAP) and Land

Information Systems (LIS) Implementation: The Issues

Dr. Isaac Bonsu KARIKARI, Ghana

This article in .pdf-format

This article in .pdf-format

1)

This article has been prepared for the 5th FIG Regional Conference -

Promoting Land Administration and Good Governance to be held in Accra,

Ghana, March 8-11, 2006.

Key words: Land administration; Ghana; LAP’s Institutional Reform

Proposals; GIS/LIS project implementation.

1. INTRODUCTION

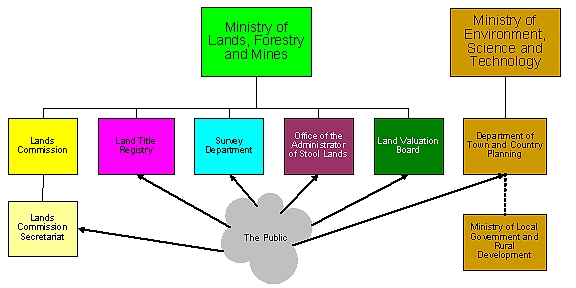

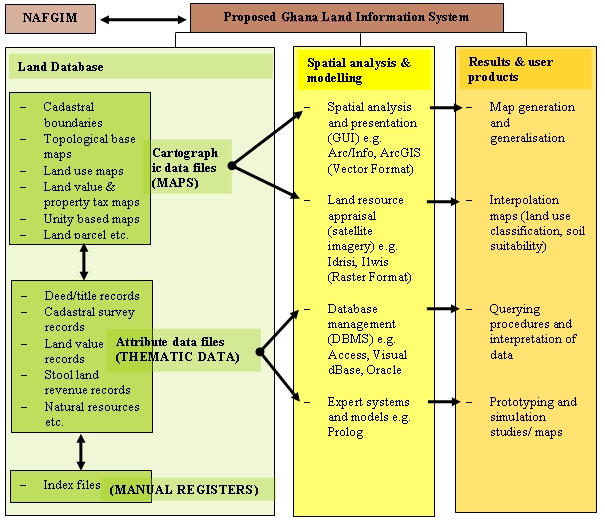

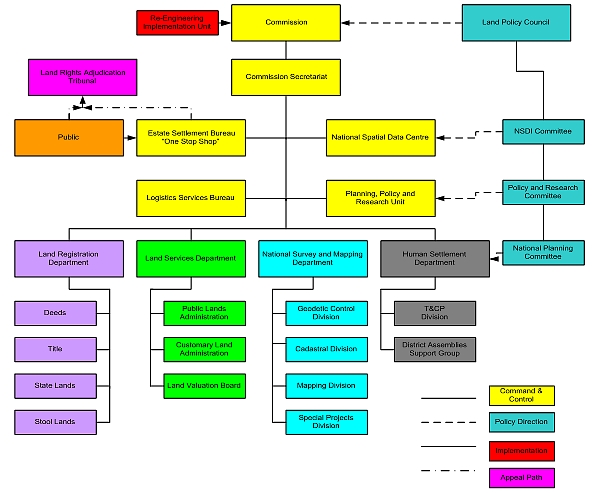

There are six land sector agencies involved in Ghana’s land

administration project (Figure 1). These agencies have technically been

operating manually in an environment beset with conflicting and unreliable

dada, dubious manipulations of existing data by some recalcitrant staff and

tedious retrieval of available information, suggesting the need to establish

or develop computer-based land information systems and networks through

re-engineering processes and pushing for attitudinal change. It is not the

manual systems per se that are the cause of the problems (although they have

contributed significantly); it is the fact that there are costs, delays and

uncertainties as well as rent seeking behaviours in the system. Generally,

details of flow-lines of information are seldom documented or monitored.

Based on better management of information, substantial improvement within

the lands sector can be brought about by analysing and costing existing

procedures, abandoning unnecessary practices and making better use of

existing resources through the introduction of Information Technology (IT)

and LIS (UNCHS (HABITAT), 1990). Essentially, most organisations would be

keen to know how LIS could fit into their overall IT strategies.

‘Land Administration’ as the process whereby land and information about

land may be effectively managed, indicating that land administration

includes the provision of information on land, identifying those people who

have interest in real estate and information about those interests such as

the nature and duration of rights in land. It also includes information

about the land parcel such as their location, size, improvements, ownership

and value. As distinct from ‘land administration’, ‘land management’ is the

process of managing the use and development of land resources in a

sustainable way. Concerned here is with ‘land administration’, even though a

‘cadastre’ could actually be a land management tool and is normally a

parcel-based land information system containing records of interest in land

(for example rights, restrictions and responsibilities associated with such

land). The UN Commission notes that effective and sustainable land

management is impossible without a cadastre or LIS.

Features:

Six independent agencies, three ministries*:

* Five under the Ministry of Lands, Forestry and Mines;

Ministry of Environment supervises Town and Country Planning at

National/Policy level, Ministry of Local Government at Local/Implementation

level

Figure 1: The six existing land agencies involved

in Ghana’s Land Administration Project

LIS and GIS have similar meanings in terms of analytical functions and

other operations performed on the data. However, the principal focus of LIS

is on the land parcel while the architecture of GIS is concerned with

mappable features (Meltz, 1989). The two terms will therefore be used

interchangeably in this paper.

LIS should also be seen as an “institutional entity reflecting an

organisational structure that integrates technology with a database,

expertise and continuing financial support over time” (Carter, 1989, p.

3). I therefore agree with Campbell (1996) that GIS diffusion is affected

not only by the nature of GIS itself but also the structure of an

organisation and the interplay of the two and depend on the extent on

how an organisation is prepared to reinvent this particular form of

technology within its organisational milieu.

The paper examines some aspects of the institutional reform proposals

suggested by the Consultant recruited by LAP, addresses topical LIS

implementation issues in Ghana’s lands sector, looks at the prospects of LIS

implementation, itemises some challenges to be faced, and gives some

recommendations and conclusions that would enable LAP achieve breakthrough

results in LIS implementation.

2. INSTITUTIONAL REFORM PROPOSALS

The land sector agencies are presently bedevilled with poor remuneration,

poor conditions of service and inadequate logistics; lack of transparency in

work processes, delays and cumbersome manual procedures; poor records

management; perceived corruption; mistrust on the part of customary land

owners in land administration generally; lack of technical expertise in new

technology available; and lack of effective collaboration and cooperation

between the agencies.

The need to reform the agencies dates back many years but it was not

until 1999 that the Government of Ghana fashioned out, for the first time, a

National Land Policy ( NLP) to give effect to this reform with a view to: “addressing

some …fundamental problems associated with land management in the country”

; “establishing and developing a land information system (LIS) and

network among related land agencies in the country; linking them up with

sub-regional and regional networks; and establishing and maintaining a

geo-spatial framework database in the Survey Department, requiring all

thematic databases to be referenced thereto” .

In October 2003, the Government launched the LAP to translate this policy

into concrete action, recognising that as Ghana moved towards increasing use

of digital technology and GIS systems, there was the need to design a

properly structured computer-based LIS that would record basic cadastral

information and better allow user access and integration within different

datasets. However, it was believed that the existing agencies had to be

placed under one management since they remained fragmented, ineffective and

inefficient in their present operations.

To give effect to this proposal a number of suggestions were made for a

new Lands Commission with one Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at the famous

Swedru Meeting 1) , namely that the:

- Government divested itself of direct management of stool lands;

- new Lands Commission was to be market focussed;

- process of re-engineering was to be implemented to reduce transaction

cost of land registration;

- law on compulsory land acquisition was to be reformed to reduce the

incentive for unnecessary acquisition of land by Government; and

- Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) remained under the

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development.

1) The six Agencies

met at Swedru in the early part of the project implementation and came out

with what is now termed the ‘Consensus Option’. This is different from the

‘Preferred Option’ as suggested by the Consultant for institutional reform.

It is worthy to note that in 2003 the Government had come out with an

Information and Communications Technology for Accelerated Development

(ICT4AD) Policy that sought to support the modernisation of the Civil and

Public Service through institutional reforms and deployment and exploitation

of ICTs to facilitate improvements in operational effectiveness, efficiency

and service delivery; and develop GIS applications to monitor and support

sustainable environment usage in cases like land and water.

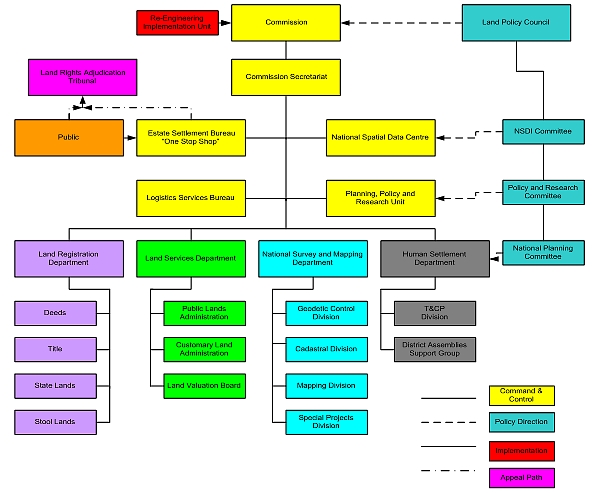

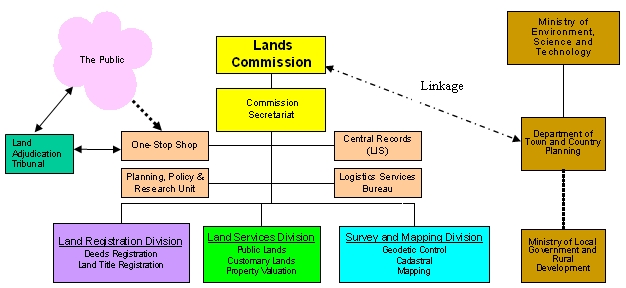

It is against this background that a consultant was recruited to suggest

the preferred institutional reform option after consultation with all

stakeholders including civil society organisations, the private sector and

traditional authorities. Figure 2 indicates the structure of the preferred

option. It is not the intention of this paper to delve into too-much detail

on this structure. The paper will only address some aspects to give the

necessary perspective to the objectives set here. It is important to

recapitulate, however, that major problems to be overcome in implementing

LIS in Ghana’s lands sector agencies will be organisational, managerial and

human based and this explains why a lot of space has been given to

institutional issues in this paper.

Source: Grant, 2004

Figure 2: The Land Administration Structure proposed by LAP the

Consultant

In Figure 2, a number of key features are easily recognisable:

- the Land Policy Council (now the Land Sector Policy Committee (LSPC)

of LAP) is expected to provide policy advice on National Land Policy to

the new Commission; the Steering Committee functions for the LAP will be

conducted by a Committee of the Land Policy Council;

- a One-Stop-Shop (Estate Settlement Bureau (ESB)) is to be adopted

where clients could have all requests on land met at a point of call. This

is to be interfaced with a Land Rights Adjudication Tribunal where the

outcome of all transactions and any Alternative Dispute Resolution or

conflict resolution may be provided subject to appeal to the Tribunal;

- National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) where an integrated

national spatial information will be developed;

- Logistic Services Bureau (LSB) where all supporting services, legal,

financial, public relations, management services and corporate facilities

will be housed;

- an Internal Audit Unit will be attached to the Board of Commissioners

for appropriate tasking and auditing within the total agency;

- the existing Land Agencies will be reorganized into four operating

departments: Land Registration Department, a Land Services Department, a

National Survey and Mapping Department, and a Human Settlement Department

(if TCPD is to be part of the One-Stop-Shop); and

- staffing and pay scales of the Commission Secretariat and Operating

Departments will be independent of civil service recruitment rules and all

conditions of service harmonised.

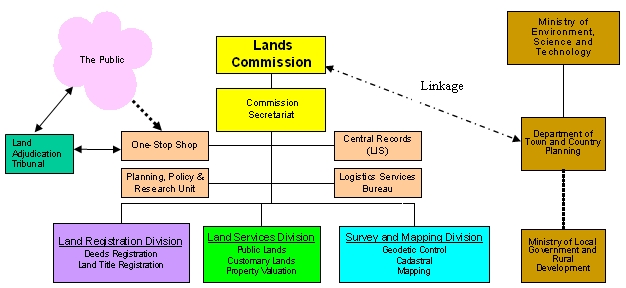

Whilst the consultant thought it possible to achieve a complete

integration of land administration services along functional lines, which

will require the merging of some units and the elimination of others and

preferred the inclusion of the Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD)

within the MLF, the LAP is pushing for a linkage between the two whilst

still resourcing the TCPD under the LAP (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Land Administration Structure

proposed by LAP to Cabinet, December 2005

Again, the NSDI initially proposed by the Consultant to be part of the

new Lands Commission structure, has given way to a LIS unit that may be

linked to Ghana’s NSDI (NAFGIM) 2)

that ought to be truly national, representing a whole-of-government

approach to gathering, sharing and presenting geo-referenced information;

and this is better placed under the National Development Planning Commission

or under the Office of the President.

2) Investigations at

the Environmental Protection Agency indicate that NAFGIM is now more or less

defunct and ought to be ‘resuscitated’.

The next part of this paper zeros in into the (Central Records) LIS

segment in Figure 3, examining in some detail LIS implementation issues. A

two-pronged approach is employed: firstly, a broad discussion on a GIS

co-ordinating mechanism for the lands agencies is established and a GIS

configuration at that level proposed. Focus is then directed to the agencies

to examine the envisaged structure and processes of GIS implementation in

the LAP and the role of the agency’s future implementation team. Thereafter,

the initial implementation requirements of the LCS including the

institutional arrangements for the GIS project implementation under

the project are considered, dwelling also on the role of GIS as a planning

support tool. Secondly, approaches and sources to learn best practices in

GIS implementation are provided as a checklist.

3. LIS PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION: THE RELEVANT ISSUES

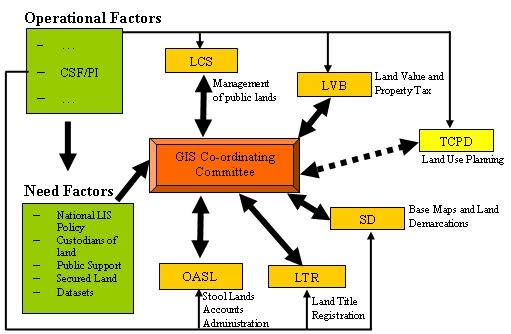

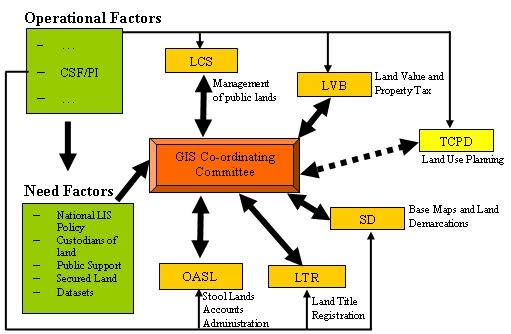

The LAP envisages a holistic approach in the introduction of GIS in land

sector agencies. Some co-ordinating mechanism has to be established for

these agencies in GIS implementation at the very outset, even before the

envisaged one-stop-service. A phased-out incremental approach is advocated.

Figure 4 shows a schematic framework for co-ordinating land sector agencies

as they currently exist.

Figure 4: Proposed GIS co-ordinating mechanisms

for the Agencies

Before Figure 4 is discussed, it is important to mention that a GIS

organisational model for the agencies would have to be based on the fact

that the LAP is gunning for the merging of the land agencies as one body. It

has, however, been noted by experts that the very nature of corporate

working (through the adoption of the enterprise model) was problematic and

that since its adoption may warrant major structural changes in

organisations involving huge financial outlays, the corporate/enterprise

model had never been actually used even by local authorities where they were

expected to be adopted widely (Campbell and Masser, 1995; Local Government

Management Board (1993); Reeve and Petch, 1999).

The proposition that, in the initial stage of implementation, each agency

should be re-engineered and strengthened as individual bodies since

re-engineering will involve creating centres of information about land

administration, land values and taxes et cetera involving the coordination

of organisational and technological change ought to be taken seriously. The

issue then would be ensuring proper networking arrangements between the

existing agencies (after re-engineering) under the GIS Coordinating

Committee that will operate as a Land Information and Management Advisory

Board, with links to Ghana’s SDI, NAGIM. GIS has a critical role to play in

this and whilst there is need for organisational reform, the ‘big bang’

approach cannot be a viable option, technically. After the merger of the

agencies the above ‘departmental approach’ may metamorphosize into a ‘GIS

enterprise model’ but only after care consideration based on empirical

evidence.

Referring back to Figure 4, each agency will have to use appropriate

suite of methodologies (for example Critical Success Factors

(CSF)/Performance Indicators (PI)) and others where appropriate

(constituting operational factors)) to determine its needs in relation to

the overall national need (need factors, that look at national GIS goals,

land as a resource, the role of custodians of such lands, the public as

stakeholders and issues relating to datasets) whilst being co-ordinated by

the GIS Coordinating Committee. The Committee is expected to oversee data

integration and ensure increased capacity for data sharing, instilling the

concept of information as a corporate resource into all the land agencies.

Each individual organisation’s long term plan must relate directly to the

long-term plans of the central government (LAP) it serves (Huxhold, 1991).

For GIS implementation, there should be clear lines of responsibility for

each participating agency and adequate incentives that allow work to be done

constructively to achieve the GIS project objectives.

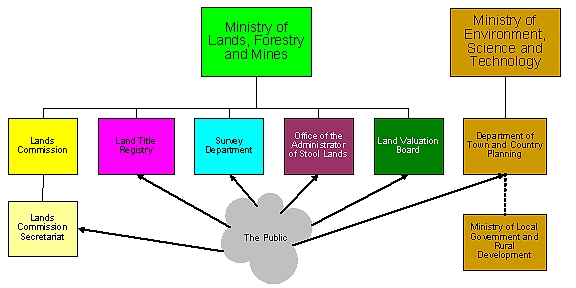

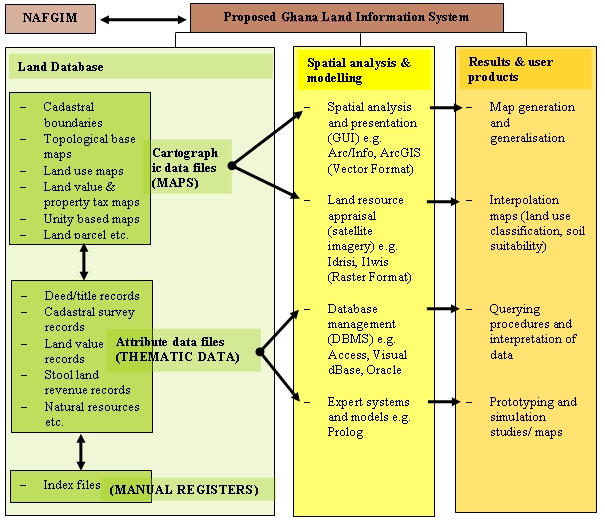

What should the LIS configuration for Ghana’s land sector under the above

co-ordinating mechanism be like? It is suggested that it comprises three

basic sections namely a ‘land database’, a ‘spatial analysis and modelling’

component and a ‘user products’ element. The land database may be divided

into three sections namely cartographic data files (maps), attribute data

file (descriptive data) and manual registers (see Figure 5 below).

Ideally, spatial analysis and modelling may have four sections. It would

utilise software with capabilities for vector and raster operations where

appropriate. It is important that standards exist to ensure effective and

efficient data sharing among agencies. Applications must conform to existing

practices and procedures simplified with the aid of expert systems and

numerical models where appropriate (Lai and Wong, 1996). A Data Base

Management System (DBMS) would be used for querying operations and

interpretation of data. It is expected that some manual systems such as

‘index’ filing would run concurrently with computer-aided information

systems.

Roles of the various departments must be spelt out early. For example

cadastral boundaries and topological base maps must be the responsibility of

the SD whilst land use maps must lie within the purview of the TCPD working

closely with SD as with all other agencies. The end result will be map

generation and generalisation (spatial data queries and analysis),

interpolation maps (land resource appraisals), querying procedures and

interpretation of the attribute data (DBMS), and prototyping and simulation

studies (expert systems and models) where appropriate.

Source: after Chidley et al. (1993)

Figure 5: Proposed GIS configuration for Ghana’s land sector

The first requirement is the automation of the agencies GIS

non-spatial database. “It is costly to collect, store and shift through

large quantities of unnecessary data. Hence, the most cost effective

approach is to collect only the data required for the specific tasks…”

Yaakup et al, 1995, p. 731). Non-graphical data in the agencies have resided

in files and are quite well indexed but most of this will still have to be

converted into digital format. It may be necessary to start with a simple

database like Microsoft Access and scale this up to Oracle in

the future. The building of spatial databases using ArcGIS, for

instance, with a customised interface can then follow at which stage

accurate master addresses or proper owner data sets would have been

obtained.

The next part of the paper dwells specifically on how implementation may

occur within those agencies.

There is to be a GIS Project Team at the Head Office (headed by a

qualified but high-ranking officer (co-ordinator)), which is expected to

play an internal co-ordinating role and be the source of technical

information for all sections of the agencies. The team will encourage user

participation, develop local expertise, demonstrate the effectiveness of GIS

technology through research and innovation and liaise with NAFGIM on GIS

standardisation and networking issues. The GIS Departments at the regional

levels will help transfer GIS technology to the regions directly and

supervise the district offices. Both regional and district levels will be

responsible for GIS implementation and therefore are to be seen operational

units. At the district level, “NGOs by their nature of their field

presence, can potentially serve as vehicles to support the transfer of GIS

technology to the district administration” (Sahay and Walsham, 1996, p.

392).

It is to be noted in Figure 5 that this proposed GIS structure must be

integrated into the present agencies systems, headed by the respect Heads of

Agencies, as far as is practicable. What is to be addressed are the roles of

these Heads of the Departments after merger. Would it be practical to make

them GIS ‘experts/godfathers’ (Reeve and Petch, 1999) and GIS ‘Project

Co-ordinators’ as well? Another issue are the roles of the new Regional

bosses as the administrative heads of the regions. Do they become hybrid GIS

managers (Reeve and Petch, 1999)? In other words, do they all necessarily

have to be retrained to become the GIS experts at the highest level in the

head office and the regions in the long run? Even though this is highly

recommended, the principal actors and users of the GIS project must

themselves decide on this. In this respect, it must be acknowledged that GIS

is to be implemented in a context in which there are going to be differing

opinions and priorities that have to be harmonised. There is a need,

therefore, to devise mechanisms that aim at maximising synergy between the

different actors and users or implementers of the GIS project (Sahay and

Walsham, 1996).

As a corollary, another critical issue is supervision of work in the GIS

units. Who supervises work at the agencies and what is to be the specific

role of the GIS Coordinating Committee? An allusion was earlier made to some

of these roles. However, it is important to state that each agency, that is

now administratively independent, is to have separate GIS teams whose role

it is to mainly develop “an appropriate set of methods for collecting,

analysing, storing and sharing information and subject these to technical

and [spatial] analysis” (Fox, 1991, p. 65). The Committee’s role will

then be catalytic only, focusing on pushing for renovations of existing

buildings to house the GIS units, ensuring training and appointment of

well-trained staff, scouting and purchasing and installing equipment

knowledgeably and seeking management support, among others. It is expected

to “either include, or allow for participation of local interest such as

private enterprises, community groups and non-governmental associations

concerned with spatial information for [land administration] purposes”

(Fox, 1991, p. 65). The Committee must ensure that there is standardisation

of data through constant contact with NAFGIM if revitalized.

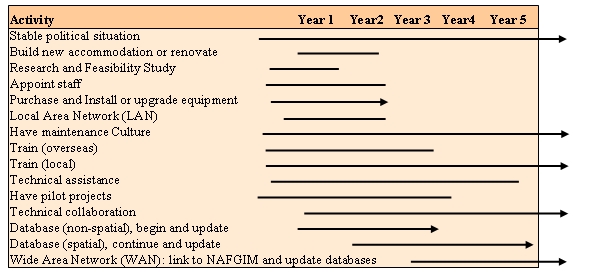

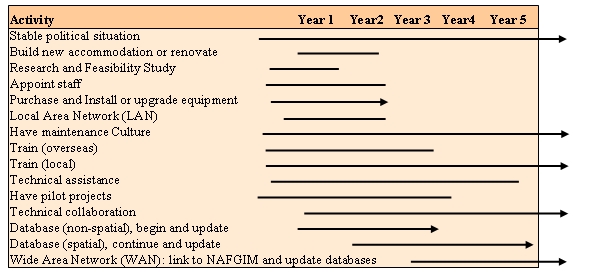

Table 1 shows examples of GIS strategic planning and choices using a bar

chart that may engage the attention of the Committee. Arrows suggest that

activities are to be sustained for a lengthy time period. After installing

equipment, for instance, they ought to be upgraded periodically over a long

period. The comprehensive long-term plan of LAP of 15 years and above will

ensure that analyses and constant appraisal of the needs of the agencies

will be consistent with the individual goals of the agencies and thus

prevent unrealised expectations and disappointments (Huxhold, 1991).

Appointment of well-trained staff, for instance, can begin shortly before

feasibility study is completed and before GIS application starts. The

acquisition and installation of GIS must be approached with a strategic plan

and choices made under a stable management environment to ensure

sustainability (de Man, 1996; Madziya et al., 1989; Geertman and Stillwell,

2002).

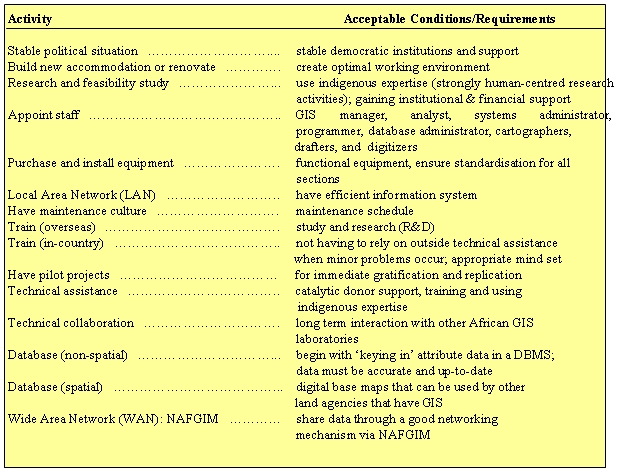

Table 1: Example of some national GIS strategic choices using a bar

chart

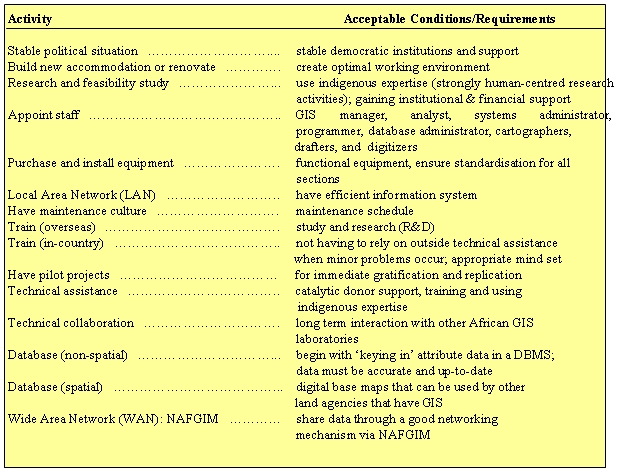

Table 2: Conditions and requirements associated with GIS strategic

choices

It is hoped that the first three years of GIS implementation will be

devoted to training of core staff abroad, providing a LAN to all agencies

whilst training in-house. Collaboration with other (African) GIS

laboratories is recommended and a maintenance culture should be cultivated

and sustained throughout the project’s life span.

Table 2 above shows the conditions and requirements associated with the

choices as indicated in Table 1. In the appointment of staff, whilst is may

be necessary to get appropriate job descriptions like the ‘systems

administrator’ in the initial stages, because the agencies would want to

develop their own applications in future, ‘computer specialists’ may later

to be seen as ‘experienced advisors or facilitators’ rather than as experts

leading the process (Reeve and Petch, 1999).

The next part of this paper relates the agencies to the national

strategic plans and choices elaborated above. Some guided steps are provided

to determine the readiness of the agencies for GIS use (Wiley, 1997).

The development of GIS must be tailored to suit specific organisations as

objectives and circumstances vary and each approach would therefore require

a different plan and treatment. A sequence of six steps has been found as

useful guide in the case of the Agencies. Each step provides a specific

activity, or a set of activities and their outputs provide information for

subsequent steps. Constraints to the introduction to GIS may be social,

economic, environmental or institutional or even legal and the design of any

interventions must be explicit. Interventions must recognise the capacity of

government, the agencies and staff to implement them and the resources

available must be specified early (Fox, 1991).

Step one: The agencies must have proper organisational structures. They

are expected to have layouts of office space and capacity to ensure the

suitable placement of equipment and easy physical circulation of staff. The

present structures in some agencies appear to create congestion. A long-term

approach of creating suitable accommodation should be included in strategic

planning of the agencies, including determining the agencies institutional

constraints on GIS use. LAP is expected to address these. The agencies

should, however, each have revised organisational charts detailing hierarchy

of responsibilities and clearly defined roles. It is worthy to note that it

was not until 1998 that an attempt was made under the prompting of the Civil

Service Performance Improvement Project (CSPIP) for any of such agencies to

have such charts.

Step two: The agencies must ensure that there are data standards for

their operations. Standards may consist of GIS guidelines on both spatial

and non-spatial data usage. Standards include the quality, reliability,

classification, accuracy and resolution of graphical and attribute data. The

agencies are expected to have good basic standards that can facilitate the

integration of other agencies’ data resources, ensuring accurate data sets

and maps.

Step three: The appropriate staff (with requisite training) must be

available (Fox, 1991; Edralin 1991). Computer specialists would be needed to

provide network support (support advisors) (Reeve and Petch, 1999). Drafters

and cartographers must be involved from the very beginning as they would be

expected to conduct updates and ensure maintenance to the database. The

transfer of trained staff should be done with some circumspection as

unplanned transfer of key project staff would create implementation

difficulties (Sahay and Walsham, 1996).

Step four: The agencies must have appropriate funding. Investments in GIS

require the need for availability of adequate funds for maintenance,

upgrades and updates of equipment and software. Future budgets must start

with current budgets and the agencies must find out what it is spending now

on information management and project into the future (Wiley, 1997). The

public and other users must pay for services provided to recover partial

expenses of the GIS development.

Step five: The agencies must create and have a maintenance culture. It is

pertinent to note that ‘the Ghanaian has no maintenance culture’ and

therefore programmes to ensure that all equipment remain functional at all

times is critical to GIS operations. An Estate Manager with knowledge in

facility management, a Database Administrator and a Systems Administrator

responsible for maintaining the system in a continuous operational mode,

among others, must be employed.

Step six: The agencies must ensure data sharing. Since this would be the

agencies first attempt at seeking data integration with other agencies, they

must embrace the policies on data standards and sharing; and the role of

NAFGIM as a ‘SDI and Clearing House unit’ in Ghana is crucial in this

respect.

The above six steps and the detailed procedures, are by no means

exhaustive, and should not be followed rigidly or sequentially as they are

not to be seen as linear. They could be varied and adapted to make the best

of every situation at any one point in time. What is important is to

understand the purpose of each step or detailed procedure and modify or

change them to suit specific circumstances. It is not being projected here

that without these requirements, GIS cannot be initiated as these are only

guides for effective implementation of GIS in the agencies at the

micro-level.

With GIS, as with any planning support systems, the agencies must list

their GIS tasks and identify staff and users who will operate the system,

set out the resources needed and estimate the time needed to accomplish

various tasks and activities. They must also have on their drawing boards,

which tasks are to be completed before others are commenced, draw up work

plans for their projects as a whole, draw individual personal work plans and

allocate money and equipment appropriately. In much more detail, they must

arrange administrative matters and logistics well in advance such as

checking and arranging security clearances for staff and equipment in the

use of maps and computers. They must budget for staff, equipment and

transport costs, provide and co-ordinate technical support in consultation

with LAP and make provisions for contingencies and iteration of steps in the

GIS planning process (FAO, 1993).

The GIS projects must be made to evolve and systems development must take

place in an incremental manner (Sahay and Walsham, 1996). On this score, it

may not be too appropriate to begin with a critical path analysis as changes

are expected to occur frequently. Based on the concept of a preceding

activity, a critical path analysis is a task which has to be completed

before another can be started (FAO, 1993). However, a detailed work plan

(e.g. a planning table or bar chart) as indicated above, when followed but

underpinned with modifications and innovations as changes would allow, can

be an invaluable tool to GIS implementation success in the agencies.

What issues are to guide the agencies in implementing GIS? The next part

of this paper will be devoted to actual experiences of GIS implementation

findings and their sources to help learn useful lessons. This operates as a

checklist for GIS implementation (see Table 3 below). It has become

imperative to learn from best practice and experience in GIS development so

as not to be seen to be reinventing the wheel.

|

Lessons reported about institutions or individuals in GIS

implementation

|

Madziya et al. (1989):

- political support is critical;

- public organisations need low-risk GIS solutions; and

- acquisition must be approached with a strategic plan.

Rourk (1989):

- institution process flows to be altered or replaced by the GIS must be

well understood;

- employees must be involved in the development; and

- lines of communication among developers, users and management must be

established.

Levinsohn (1989):

- all agencies affected should be involved early in the process;

- full range of key decision makers, line managers and technical staff

should be involved throughout;

- executive commitment is highly important; and

- consensus building is required as opposed to implementation by

directive.

Fox (1991):

- failure to adopt a new technology because of constraints has

consequences and foreseen consequences can become constraints;

- culture of government organs strongly influence the adoption of

information technology;

- establishment and operation of these systems require a large number of

specialist with broad experience and knowledge; and

- organisations are affected by their structure and order.

Sahay and Walsham (1996):

- balance between technical and social;

- transitions to GIS are made in a gradual rather than an abrupt manner;

- actors must work together as a team for the progress of the project;

and

- develop mechanism that maximises synergy between actors.

Campbell (1994):

Four factors that enhances successful GIS implementation:

- simple applications fundamental to the work of potential users;

- user directed implementation involving all stakeholders;

- awareness of the limitations of the organization; and

- high degree of organisational stability or the organisation’s ability

to cope with change.

Lai and Wong, (1996):

There must be:

- simultaneous adjustments between users practices and technological

evolution;

- changes in operating procedures, service provision and power relations

in organisations;

- integration of local (indigenous) knowledge and established

(exogenous) knowledge;

- standardisation of development visions to gain common ground among

major participants;

- progress toward achieving systems that are easy to use; and

- long-term development that requires continual funding and elaborate

support infrastructure.

Speer, (1997):

- the presence (or absence) of ‘project champions’ will likely dictate

the success (or failure) of the project.

Reeve and Petch, (1999):

- GIS project leaders need to be sensitive to the nuances of the

organisation in which they work; and

- People are the key to GIS success.

Nebert (2001): On the concept of SDI

- ensure key government, commercial and value-added data/related service

providers are represented as key stakeholders in the development and

implementation of national SDI;

- collaboration of government data suppliers on coordinated, supportive

policies that relate to spatial data access and distribution including

availability of free data, pricing, copyright and use/integration of

electronic commerce;

- an access infrastructure and policy that is non-threatening to

stakeholder mandates;

- sustainable long term business models;

- early and clear indication of the role of the private sector;

- early marketing and promotion of the entire SDI programme;

- awareness and adoption of international standards;

- organisations must prioritise their data;

- organisations to collect metadata a little at a time; and

- organisations must publish their metadata using OpenGIS Consortium

Catalogue Services Specification.

Geertman and Stillwell, (2002)

- characteristics of the policy context (e.g. democracy or dictatorship)

influence the preferred technology and the way it is used.

Dunn, (2002)

- appropriate uses of GIS were those that consider first the political,

social and institutional context before providing technical evaluation;

and

- those projects that are most likely to fail are those in which

technocratic ‘quick fix’ approaches are adopted.

Karikari, Stillwell and Carver (2003a)

- the successful initiation [and implementation] of GIS pilot

projects by Ghanaian experts will depend on a strong financial base

and a strong management support (with GIS champion(s) playing vital

roles);

- strong management support and strong financial base

would indicate the readiness for GIS use [and implementation];

- the readiness for GIS [implementation] would depend on the

political and economic situation of the country with donor countries

playing catalytic roles; and

- any successful GIS prototype or pilot must be well

documented to ensure continuous funding (from within) and

therefore ensure sustainability.

Karikari, Stillwell and Carver (2003b)

- if NAFGIM is it to ensure the full realisation of the potential of

geospatial information technologies, then it must resuscitated and made to

develop a strong business case and have an aggressive campaign to sell the

concept of SDI in Ghana.

Table 3: Typical examples of GIS

implementation findings to help learn useful lessons

|

4. RECOMMENDATIONS

Ghana’s Land Sector Agencies must:

- determine that envisaged LIS pilots are administratively workable with

the view to involving the ultimate end users (the public and custodians of

land); have a phased approach, starting with research or adaptive work

(involving these pilot projects) that is scaled up subsequently as

experience demands, before a full-scale application is embarked upon;

- involve requisite staff from the outset;

- ensure that prospects are reasonable that adequate funding will be

available from within (current budget) and if needed from without

(LAP financial assistance);

- improve their performance through more stable appointment policies;

- reassess the staff strength with the view to rationalising their

structures and promoting competent professional staff on the basis of

merit;

- clarify their obligations and prerogatives with the objective of

ensuring accountability of management;

- give a sustained effort at building up their information systems and

analytical capacity through human resource development and research;

- evolve strategies aimed at removing or reducing corruption to improve

their image;

- improve conditions of service and pay levels;

- retrain professional staff to cope adequately with work processes

through a focused and continuous training programme (including study

tours/conferences) in IT, GIS and land related courses;

- create sinking funds or revolving funds from the very outset to be

replenished periodically, purely for maintenance of equipment and

back-ups;

- have an internal independent audit teams;

- ensure that charges on services provided are determined by the

interplay of the forces of supply and demand as far as practicable;

- improve financial performance by removing or reducing waste, raising

operating efficiency, exercising better control of inventories and

improving billing and collection of ground rents among others;

- set milestones, pausing and ascertaining reasons for successes chalked

and problems encountered; and have these well documented during and after

each pilot’s implementation stage;

- recognise that appropriate staff with training in IT and GIS will be

sine qua non in their work processes and in the successful

implementation of the LAP;

- recognise that once trained, such professionals need to be motivated

to stay in LC through incentives and good remuneration;

- recognise that cultural change is needed if LAP is to be successful;

- consider making data analysis on land data part of the agency’s

mission;

- acknowledge that Ghanaians lack a maintenance culture and recognise

that the ‘triad’ in IT are hardware, software and expertise; and

that maintenance of equipment and upgrading of software and back-ups must

be planned from the very outset and carried out promptly following

well-planned maintenance schedules;

- watch attitudes; and

- concentrate on the Big Picture (LAP).

It is recommended that LAP itself be repositioned:

- LAP should restrict itself to facilitating and monitoring the project.

(It should ensure project management/control, monitoring and evaluation

only);

- components of LAP, with the exception of Component 4 (dealing with

monitoring and evaluation and project management), must be headed by

Agency Team Leaders based as much as possible on current mandates. Agency

Team Leaders must be empowered;

- implementation must occur at ‘Implementation Agency’ level where all

pilots, including GIS ones, must be done: There is the need, in this

regard, to develop a deep sense of ownership by making use of the LAPs

Regional Co-ordinators as far as practicable; and

- LAP must resource and strengthen the Agencies and relevant

stakeholders by providing sustained logistical support, material and human

resources development. Procurement must be decentralised to these agencies

as far as practicable).

5. CONCLUSION

The underlying concern in this paper is that land must be better managed

in Ghana, and this involves a better land-information management, the

monitoring and modelling of such phenomenon as land use change and

encroachments. In this context, it is observed that the successful

implementation of GIS to support land administration in the lands sector in

Ghana will be confronted with a series of challenges: the need to provide

frameworks within which GIS can evolve as a tool in an orderly way in the

Land Sector Agencies; the need to find ways to democratise GIS in land

administration and management systems and structures within Ghana; the need

to generate designs that are innovative and practical so they will meet

specific land sector needs; and the need to provide support infrastructure

and services that will enable GIS to operate effectively and efficiently in

the lands sector in relation to other sectors. Each of the agencies will

have to be re-engineered, at the very outset, to improve efficiency and

effectiveness in the delivery of services that are provided to the user.

This calls for the urgent need to identify weaknesses, bottlenecks,

inefficiencies, duplication, threats and opportunities in respective

agencies. On this note, the agencies must recognise that major problems to

be overcome in improving land information practices will be organisational,

managerial and human based. It is the way in which the responsibility for

land data is to be allocated and distributed between institutions, how

records are to be kept and administered and on the skill and education of

the people who are expected to run these systems that would determine their

success and failure, and not the technology employed (Karikari et al. 2005,

p. 358).

REFERENCES

- Campbell, H., 1994, How effective are GIS in practice? A case study of

British local government. International Journal of Geographic Information

Systems 8, 309-325.

- Campbell, H., 1996, Theoretical perspective of diffusion of GIS

technologies. In Masser, I., Campbell H., and Craglia M., (eds), 1996, GIS

Diffusion: Adoption and Use of Geographic Information Systems in Local

Government in Europe (London: Taylor & Francis).

- Campbell, H., and Masser, I., 1995, GIS and Organisations: How

Effective are GIS in Practice (London: Taylor & Francis).

- Carter, J. R., 1989, On defining the Geographic Information System. In

W. T. Ripple (ed.), Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems: A

compendium (Falls Church: VA., ASPRS/ACSM).

- Chidley, T. R. E., Elgy, J., and Antoine, J., 1993, Computerised

Systems of Land Resources Appraisal for Agricultural Development, Land and

Water Division, FAO.

- De Man, W. H. E., 1996, Geographical information technology in support

of local planning and decision-making: Challenges and opportunities for

Southeast Asia. In Tung Fung et al., (eds), GIS Asia, 195-199.

- Dunn, C., 2002, GIS for development in lower-income countries. ITC

News, No.1, Enschede, The Netherlands, 27-28.

- Edralin, J., 1990, Conference Report - International Conference on

Geographical Information Systems: Application of Urban Regional Planning,

Nagoya, UNCRD: 1.

- FAO, 1993, Guidelines for Land-Use Planning, Food and Agriculture

Organisation of the United Nations Development Series 1, Rome.

- Fox, J. M., 1991, Spatial information for resource management in Asia:

A review of institutional issues. International Journal of Geographical

Information Systems, Vol. 5, No. 1, 59-72.

- Geertman, S., and Stillwell, J., 2002, Planning Support Systems in

Practice (Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag).

- Grant, D., 2004, Institutional Arrangements, Lands Sector, Ghana,

Unpublished Paper, Ministry of Lands, Forestry and Mines, Accra.

- Huxhold, W. E., 1991, An Introduction to Urban GIS (New York: Oxford

University Press), 230-268.

- Karikari, I., Stillwell, J., and Carver, S., 2003a, Land

administration and GIS: The case of Ghana, Progress in Development

Studies, 33, 223-242.

- Karikari, I., Stillwell, J., and Carver, S., 2003b, GIS adoption in

Ghana’s lands sector agencies: futuristic organisational model and

development stages for the Accra Lands Commission Secretariat (LCS). Our

Common Estates, RICS Foundation.

- Karikari, I., Stillwell, J., and Carver, S., 2005, The application of

GIS in the lands sector of a developing country: Challenges facing land

administrators in Ghana, International Journal of Geographical Information

Science, Vol. 19, No. 3, 343-362.

- Lai, P-C and Wong, M-K, 1996, Problems and prospects of GIS

development in Asia. In Tung Fung et al., (eds), GIS in Asia: Selected

papers of the Asia GIS/LIS, AM/FM and Spatial Analysis Conference,

219-229.

- Levinsohn, A. G., 1989, A strategic planning based approach to the

design of land information systems. Proceedings of the Urban and Regional

Information Systems Association, Vol. 2: 30-38.

- Local Government Management Board, 1993, Benchmarking Guidelines: A

Guide to Evaluation (Luton: LGMB).

- Madziya, R.G., Mattiussi, R., and Willis, G., 1989, Doing it right: An

information management system. In Bijan Azad (ed.), Proceedings of the

Urban and Regional Information Systems Association, Vol. 3, 1-9.

- Meltz, S., 1988, An approach for implementing land information systems

for rural and urbanising counties. Surveying and Mapping, 48, 35.

- Nebert, D. D. (ed.), 2001, Developing Spatial Data Infrastructures:

The SDI Cookbook, Technical Working Group, Global Spatial Data

Infrastructure (GSD1), Version 1.1, May.

- Reeve, D. E., and Petch, J. R., 1999, GIS, Organisations and People: A

Socio-technical Approach (London: Taylor and Francis).

- Rourk, R. W., 1989, Conquering the GIS implementation curve through

successful pilot project studies. Proceedings of the Urban and Regional

Information Systems Association, Vol. 2, 76-87.

- Sahay, S., and Walsham, G., 1996, Implementation of GIS in India:

Organisational issues and implications. International Journal of

Geographical Information Systems, Vol. 10, No. 4, 385-404.

- Speer, E. D., 1997, Implementation Issues of GIS Applications in

Developing Countries, (http://www.esri.com/library/userc…oc97/proc97/to

- accessed March 2001).

- UNCHS (HABITAT), 1990, Guidelines for the Implementation of Land

Registration and Land Information Systems in Developing Countries: with

Special Reference to English Speaking Countries in Eastern, Central and

Southern Africa, Nairobi.

- Wiley, L. 1997, Think evolution, not revolution, for effective GIS

implementation. GIS World Inc., 10, 4, 48-51.

- Wiley, L. 1997, Think evolution, not revolution, for effective GIS

implementation. GIS World Inc., 10, 4, 48-51.

- Yaakup, A., Ibrahim, M., and Johar, F., 1995, Incorporating GIS into

Sustainable Urban and Regional Planning: The Malaysian Case. Proceedings

of Geoinformatics ‘95, Vol. II, Hong Kong, 26th - 28th May, 728-736.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dr Isaac Bonsu Karikari is a Principal Lands Officer with the

Lands Commission, Accra. He is a Core Team Member (Advisor on Land

Administration) to the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), Ministry of

Finance and Economic Planning, Ghana and the Lands Commission’s Team Leader

of the World Bank’s supported Land Administration Project. He is also the

Head of Geographic Information Systems, Training and Manpower Development

Unit of the Commission). He is an Associate Member of the Ghana Institution

of Surveyors, Chair of the Research and Development (R&D) Sub-Committee of

General Practice Division of that Institution; a Member of the Board of

Examiners (BOE) of General Practice Division; and Local Chairman, Scientific

Committee for the 5th FIG Regional Conference on ‘Promoting Land

Administration and Good Governance’, Accra, Ghana, March 9-12, 2006.

CONTACT

Dr Isaac Bonsu Karikari

Lands Commission Secretariat

PO Box CT 5008

Cantonments

Accra

GHANA

Tel. + 233 21 777325 (office)

Fax + 233 21 761840

Mobile: + 233 24 3103439

Email:

drisaackarikari@yahoo.co.uk

|