Article of the Month -

June 2014

|

THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA:

The World’s Greatest Boundary Monument!

John BROCK, Australia

1) This paper investigates

which portions of The Great Wall(s) of China were mainly erected as

boundary demarcations and the others put up as protection as well as

attempting to highlight early techniques and equipment used by the

Chinese surveyors of antiquity hopefully supplemented by some translated

texts and historic art. The paper will be presented Friday 20 June 2014

at the History Symposium held in conjunction with the 2014 FIG Congress

in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. The History Symposium is organized by the

International Institution for the History of Surveying and Measurement,

a Permanent Institution within FIG,

http://www.fig.net/fig2014/history.htm.

ABSTRACT

”… in the endeavors of mathematical surveying,

China’s accomplishments exceeded those realized in the West by about one

thousand years.”

Frank Swetz – last line in The Sea Island Mathematical

Manual: Surveying and Mathematics in Ancient China.

It is said that the Great Wall of China is the only

manmade structure on Earth which is visible from space (not from the

Moon)! The only natural feature similarly identifiable from the outer

reaches past our atmospheric zone has been named as Australia’s Great

Barrier Reef. This natural wonder of the sea is continuous while the

Great Wall of China is actually made up of a series of castellated walls

mainly erected along ridge lines causing major variations in the levels

of its trafficable upper surface. Some of the barriers built are not

formed from stone but from rammed earth mounds.

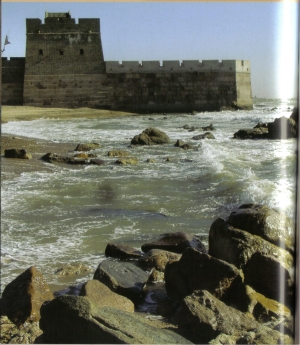

Fig. 1 The moon from The Great Wall instead of

vice versa which cannot actually occur !!!

The purpose for these walls was primarily to

facilitate protection from hostile adjoining tribes and marauding hordes

of enemy armies intent on looting and pillaging the coffers of its

neighbouring wealthier Chinese Dynasty of the time. As the need for

larger numbers of military troops became required to defeat the stronger

opponents, which may sometimes have formed alliances, the more astute

provincial rulers saw a similar advantage in the unification of the

disparate Chinese Provinces particularly during the Ming Dynasty

(1368-1644). In fact the earlier sections of the Great Wall(s) were

constructed to delineate the territorial areas of separately governed

principalities thus representing some of the most ancient continuous

boundary monuments of substance still surviving to this day. This paper

will investigate which portions of The Great Wall(s) of China were

mainly erected as boundary demarcations and the others put up as

protection as well as attempting to highlight early techniques and

equipment used by the Chinese surveyors of antiquity hopefully

supplemented by some translated texts and historic art.

INTRODUCTION

When it comes to the imagination of world peoples The

Seven Wonders of the World holds curiosity of conversation usually when

called upon to name any series of such groups of seven including dwarfs,

deadly sins and so on. Due to the magnitude of its extent The Great Wall

of China quite often is put forward (wrongly) as one of these seven

man-made constructions of amazement. Erected over a vast expanse of

history the “Chinese Wonder” is certainly one of the most visited

edifices by modern tourists but what is available for public viewing is

a mere fragment of the actual 21,196 kilometres of the overall lineal

coverage of the various features included among what has become known as

The Great Wall. Only in the last few years from 2007 has this survey

accurate total been determined through a joint project by China’s State

Administration of Cultural Heritage and the State Bureau of Surveying

and Mapping with the existing previous estimate at that time being less

than half of the true length at a mere 8,850 kilometres ! From the

popular perception the section of The Wall built of stone in the

vicinity of Badaling, near Beijing, has become the vision most

representative of this iconic structure due to its substantial material,

excellent restoration and open accessibility for viewing. Although the

steeply disparate levels of the Wall’s floor area make movement rather

difficult the public authorities responsible for its maintenance and

availability have had handrails installed to assist visitors to pull

themselves up the demanding slopes. My thoughts instantly pondered as to

how the heavily clad Chinese warriors could possibly negotiate such

forbidding barriers of non-evenness as those existing along most of The

Wall where it stood imposingly atop ridgelines separating the northern

territories from the Chinese lands to the south. Then of course, being

the inquisitive surveyor that I am, my next immediate thought was that

how this famous line of walls actually separated the land of one peoples

from those occupied by a rival nation thus being a visible boundary

monument for the delineation of designated lands. By sheer definition

both physically and notionally a wall is erected to “divide” one area

from another thus representing a barrier or borderline across which

incursions are only welcome by invitation or imposed by the invasion of

one neighbour onto the territory of the other. Surveyors always find

fascination and interest in boundary lines with particular attention

directed to what has been placed to define such lines of territorial

demarcation so along with concern about boundary markers comes a

consideration of who actually placed them and how they were surveyed.

Uncovering source material about the ancient Chinese surveyors has not

been easy due to the language barrier between English and Chinese as

well as the long periods of banishment of foreign inquisition and

examination imposed by the Imperial Chinese decrees of isolation

intended to maintain the non-contaminated superior Chinese lifestyle.

However my determination has paid off through my discovery of a

brilliant English text by Professor Frank J. Swetz on Chinese

mathematics as it so pertains to surveying purchased from the

Pennsylvania State University Press via the internet for a very

reasonable fee which also included packaging and postage. The much

anticipated publication arrived in very quick time indeed !

CHINA’S GREAT SURVEYORS

|

“The Sea Island Mathematical Manual:

Surveying and Mathematics in Ancient China” by Frank J. Swetz is

an examination of a Chinese teaching text called the Haidao

Suanjing (translated as the Sea Island Mathematical Manual)

compiled in 263 AD by Liu Hui, an official during the Kingdom of

Wei (220-290 AD).also known as the Three Kingdom Period, being a

somewhat unsettled time under the reign of an emperor named Cao

Pei. Nine problems associated with varying situations of field

surveying are solved using the application of right angled

triangles confining such hypotheses to micro-scale land areas

within which the subject areas can be assumed to be planar and

thus unaffected by any considerations of earth curvature or such

spheroidal nuances. In the earliest known Chinese mathematical

text the Zhoubi Suanjing (translated as Perimeter Gnomon

Manual), published between 100 BC and 100 AD, the material

published represents established surveying practices including

accomplished application of right triangle theorem in operation

for hundreds of years. With this long history in mind the period

mentioned clearly covers the lifetimes of the legendary Grecian

Fathers of Geometry Thales (624-527 BC) and Pythagoras (569-475

BC) so the level and extent of mathematical knowledge and |

|

|

accomplishment of the Chinese is truly

remarkable indeed. To clarify the subjects covered in this

ancient corpus of knowledge it is necessary to define “zhou” as

“perimeter” and “bi” as “gnomon” being a shadow staff for

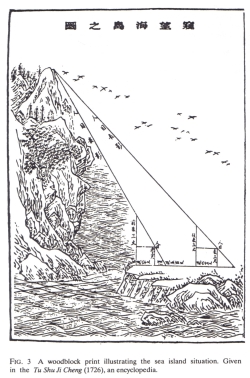

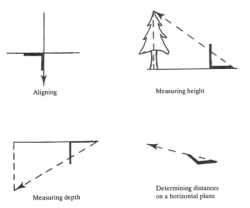

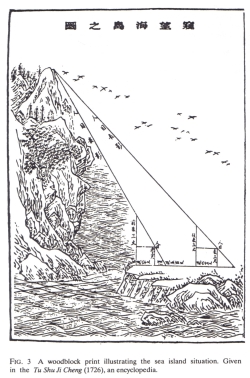

position reckoning by the sun. Also employed by the Chinese was

the set square (ju) to determine the heights of remote objects

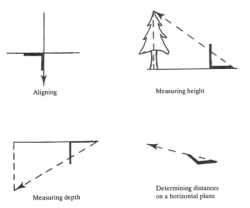

through the proportional geometry of triangles (see Figure 3).

To measure distance the ancient Chinese mensors used the

customary rope which in more recent times was replaced by tapes

and long wires supplemented with the use of plumb bobs for line

propagation and horizontality. |

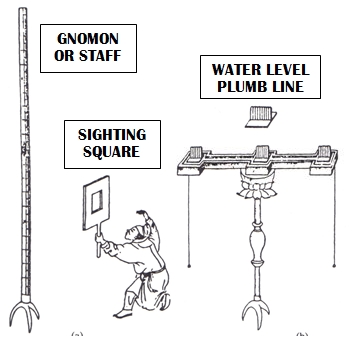

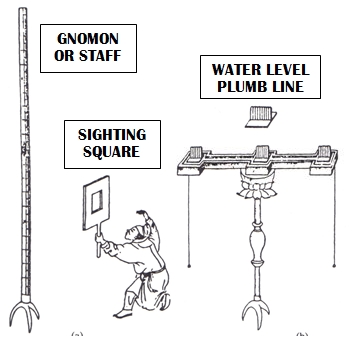

Fig. 4 Chinese surveying equipment of the ancients.

Surveying tools from ancient China are well testified

through artwork, artifacts and descriptions being sighting or reference

poles (gnomons), biao; set square, ju; plumb line, xian; water level,

zhun, ropes and cords later replaced by tapes, bu che. As more commonly

known in English as “The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the

Circular Paths of Heaven” dated to circa 100 BC - 100 AD, it takes the

form of a discussion between Zhou duke Zhou Gong and a Grand Prefect

called Shang Gao when the nobleman asks of the official: “May I ask how

to use the set square?” to which the response comes: “Align the set

square with the plumb line to determine the horizontal, lay the set

square down to measure height, reverse the set square to measure depth,

lay the set square down to determine distance. By revolving the set

square about its vertex a circle can be formed, combining two set

squares forms a square.” (see Figure 5) The length standards and

languages adopted were quite variable before Emperor Zheng took power in

221 BC after defeating the provinces of the weaker leaders to earn the

title of The First Emperor. Through his rigidly despotic regime he

introduced a single currency, standards for weights and measures as well

reducing the alphabet down to a mere 3,000 characters in a single spoken

dialect ?!? Putting into practice the new specifications of mensuration

surveying devices were made to differing lengths depending on the

accuracy required, with sighting poles quoted to be 20 and 30 chi

respectively in the problems of the Haidao being the equivalent of 7 and

10.5 metres. The standard Chinese set square for field use had sides of

2 chi (0.7 metre) but could be made to lengths of 12 or 23 chi plus (4.2

or 9.1+ metres) to achieve finer results.

The Haidao Suanjing was the mathematical aid to solve

the field problems which confronted the surveyors consisting of nine

individual circumstances summarised as:

-

The sea island problem to calculate the

height of a remote island;

-

The pine tree problem to ascertain the

height of a distant tree;

-

Size of a distant walled city problem;

-

Depth of a ravine problem;

-

Height of a building as viewed from a

hill problem;

-

Width of a river mouth problem;

-

Depth of a clear pool problem;

-

Width of a river problem an

-

Size of a city from above problem.

|

Fig. 5 Set square measurements as per

some from The Haidao Suanjing. |

Considering Chapter Nine of this contemporary text to

be inadequate for precise measurements Liu introduced a method of

calculation called chong cha (translated as “double difference”), a

concept well understood and employed by all prudent surveyors as a

mechanism to compensate for systematic errors present in monitoring

equipment being readily eliminated by repeat observations at 180 degree

orientation.

The essential work of the surveyors in Imperial China

was directed towards the four purposes as listed:

-

Mapping required for the existence and

maintenance of the political state;

-

Verification of cadastral land boundaries for

ownership and taxation;

-

Supervision of public works such as roads,

aqueducts and canals and

-

Warfare reconnaissance and target assessment.

Such considerations are elements of all the great

civilizations in their expectations and demands upon their land

surveyors with particular recognition of the skill and authority

demonstrated by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. From the most

ancient Chinese classics instructions pertaining to waging war contained

references to the vital need for accurate mapping and techniques to

determine the position of the enemy from satellite posts. From before

the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) such as Zhou Dynasty (1025-256 BC) classics

as the Zhou Li (Rites of the Zhou Dynasty), Zhan Guo Ce (Records of the

Warring States), Guan Zi (The Book of Master Guan), Sun Zi Bing Fa

(Master Sun’s Art of War – 5th century BC) and Sun Bin Bing Fa (Sun

Bin’s Art of War – 4th century BC) the existence and use of maps were

cited on many occasions.

SURVEYING IN CHINESE MYTHICAL LEGEND

As far back as around the 29th century BC Chinese

mythology has an event supporting a Noah’s Ark Biblical epic of a Great

Flood which wiped out the world with the only survivors being Fu Xi and

his wife (who may also have been his sister?) Nu Wa who held equal

status with her husband in Taoist tradition for repopulating the Earth

with the tools of creation – the compass and set square! It is indeed

prophetic for the future surveyors of China that these two instruments

of myth would become their own devices for carrying out their survey

tasks. Fu Xi is variously said to have ruled as “The First Emperor” (of

folklore!) for over 115 years commencing in either 2952 or 2852 BC. As a

folk legend this guy had everything useful to a surveyor in the wild

bush land as he was said to have been a shaman who could tame wild

creatures as well as being capable of controlling the weather.

Furthermore he is credited with inventing many things among which were

cooking, trapping, fishing, music, writing, the calendar and angle

measurement! When images of Fu and Nu are shown Fu holds the compass and

Nu the set square with their snake-like bodies intertwined. This pair

would appear to me to represent an archetypal couple of Surveyor Gods to

which the later surveyors may have called upon for heavenly guidance

during their surveying assignments.

MAPS FROM ANTIQUITY

During 1973 an archaeological dig of a Han Dynasty

tomb at Mawangdui in the south west region of Changsha discovered three

silk maps of a marquisate dated to the Western Han period (206 BC to 6

AD). One of the silken charts was drawn at an approximate scale of

1:180,000 depicting mountain ranges, rivers, occupied areas and

topographical features with contours. Through a comparison with a modern

map of the same area it was very clear that the surveyors and

cartographers who contributed to the historic work must have been

capable of reliable and highly precise map production. One of the charts

was prepared to plot troop locations within the designated mapping zone.

Regarded as the Father of Chinese Cartography Pei Xiu

(AD 223-271) was made Minister of Works in 267 by the first emperor of

the unified Jin Dynasty (265-316). He assembled all known cartographic

works at that time postulating the following set of six principles for

good map making:

-

The use of an appropriate scale in drawing;

-

The employment of a rectangular grid system;

-

Accurate measurements between major landmarks

including the projection

onto a plane of those with different elevations precisely executed;

-

Determination of accurate elevations;

-

Measurement of right and acute angles and

-

Measurement of curves and straight lines.

As each of the pronounced principles required a

working comprehension of the use of right angled triangles

mathematically it formed the basis of the Chinese surveying and

cartographic process for the facilitation of the surveying and

preparation of most reliable and impressive maps from the mysterious

empire. Military needs were the not the only area to which such

standards of precision and accuracy were applied by the Chinese

autocracy. Due to the common occupation of areas adjacent to or nearby

to rivers and estuaries careful planning was carried out to design civil

works for the diversion of waterways through canals and irrigation, all

of which demanded a high level of correctness and skill to make

preliminary reconnaissance surveys followed by the precision necessary

to construct such intricate systems of water utilisation. Such respect

was held for the surveying skill commensurate with the very survival of

the populace translated onto the godlike qualities of the revered

leaders of China when the legendary emperor/engineer Yu the Great

(c.2200-2100 BC, Xia Dynasty) (also often depicted with a set square in

hand!) was described in the following way:

“Emperor Yu quells the flood, he deepens rivers and

streams, observes

the shape of the mountains and valleys, surveys the high

and low places,

relieves the greatest calamities and saves the people from danger. He

leads the floods east into the sea and ensures no flooding or drowning.

This is made possible because of the Gougu right triangle theorem.”

During early periods the term for astronomers and

surveyors were exactly the same, chou jen or literally “surveyors of

heaven” which clearly portrays the divine status bestowed upon China’s

ancient surveyors.

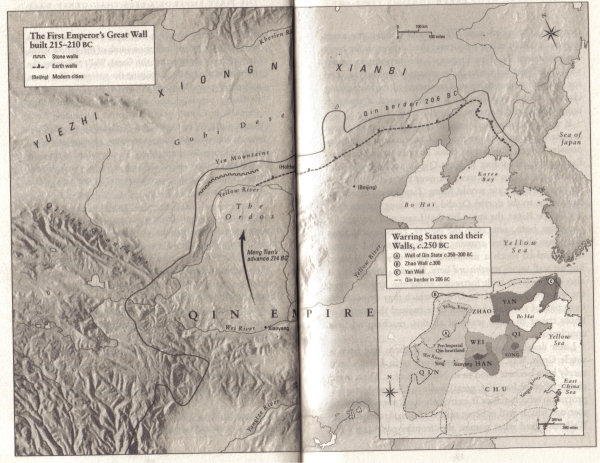

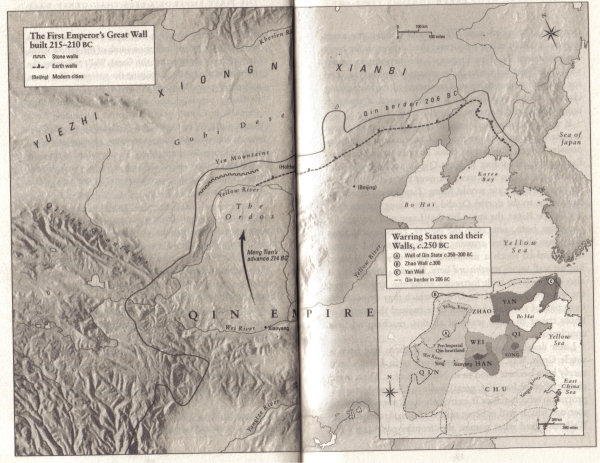

EMERGENCE OF THE WALL

Prior to the unification made under Zheng’s

dictatorship in 221 BC China consisted of a diverse group of what was

termed The Warring States mainly focused on the preservation of their

limited principalities from the territorial ambitions of their various

not-so-friendly neighbours. Thus the first series of boundary walls were

erected as defences for their own individual bits of turf, therefore

truly being boundary monuments by design. This earlier epoch was known

as the Zhou Period but was comprised of Qin, Zhao and Yan States who put

up their walls of separation for both protection and demarcation from

350 to 215 BC.

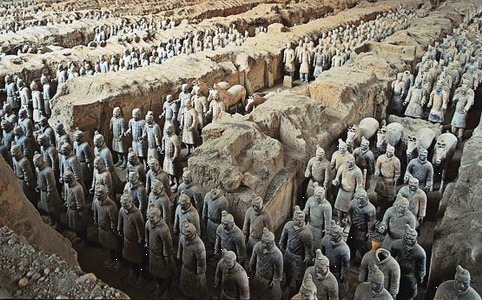

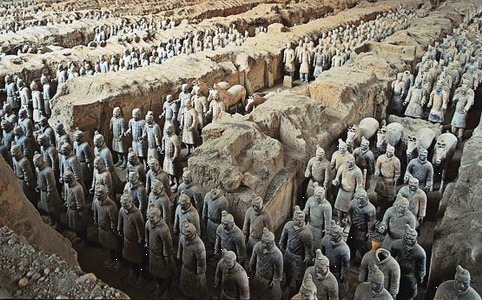

Fig. 6 The First Emperor’s heavenly guards in his spectacular burial

place in Xian.

However when Zheng took over domination of the

disparate factions he soon embarked on what history has declared to be

the commencement of Great Wall construction with the express purpose of

keeping at bay the hostile tribes to the north of this structure and in

so doing created the physical delineation of his Qin Dynasty empire in

the northerly direction. Within the relatively brief reign of just over

a decade up until 210 BC upon his death, The First Emperor had been

successful in constructing some 4,000 miles (6400 kms) of the first

Great Wall in addition to creating the other major tourist attraction of

modern China – The Terracotta Warriors guarding his tomb at Xian.

Contemporary accounts during the construction of this megalomaniacal

monument give an estimate of around 7,500 entombed statues of which only

1,000 have so far been uncovered for public viewing.

|

Extending from the Ordos ranges in the west

right through to the coast in the east this rather humble wall

in its height and substance had been the inspiration for later

rulers to build similar barriers but with more durable and

impressive material along some of the most inhospitable terrain

and precipitous ridgelines across the mainly northern area of

the Chinese empire. As this first attempt at a “Great Wall” was

clearly not impregnable to armies of horse cavalry as they only

stood at heights of 1 or 2 metres for the majority of its length

without ramparts or towers it was the mere concept of a physical

symbol to convey the message to any potential invader that to

pass across this boundary would invoke dire repercussions by the

Chinese Imperial Forces and thus it was a most emphatic border

delimitation. It is interesting to note that this “first”

attempt at a “Great Wall” was punctuated along its length by

beacon towers or pillars which were clearly placed |

Fig. 7 The First Emperor’s “Great Wall” boundary monument. |

|

for determining strategic locations or other

troop position points. Could they have also been utilized by the

surveyors for mapping and surveying activities? It is a

tantalising notion indeed! |

Fig. 8 The First Emperor’s northern boundary line as delineated by the

first “Great Wall”

The two Han Dynastic Periods from 202 BC to 220 AD

saw the western extension of this Wall. From this time onwards more

local walls were erected from 220 to 1234 while during the domination of

the Mongols from 1234 to 1368, the latter under the leadership of the

mighty Genghis Khan himself for a period, the Wall was left to natural

decay and dilapidation until the rise of the mighty Ming Dynasty.

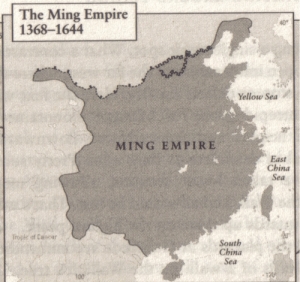

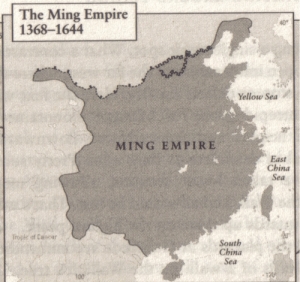

Probably more well-renowned for its treasured blue

and white ceramics the Ming Dynasty was much more than just a ruling

class of potters. After crushing the Mongol Army in 1368 the Ming

leaders could not have imagined that their dynasty would prevail right

through until 1644 when they were out-manoeurvred by the Manchus whose

reign is called the Qing Dynasty lasting until 1911.The modern populist

vision of a Great Wall of stone with crenellated ramparts and beacon

towers running along the mountain tops as far as the eye can see is owed

to the work of the Mings whose capital works program included this

monumental construction. Their intentions certainly were to fortify and

protect their territory and citizens from the ravaging marauders but by

placing their walls along ridge lines which were already natural borders

separating two different tracts of land they had unintentionally set

about placing the most famous and impressive boundary monument ever

created by man on earth.

During war and peace the Ming kept on building their

wall despite much dissension about the cost of such a capital works

program when other areas were considered to be deserving of more

priority. However up until 1568 there were still many defensive gaps in

the wall and hardly any beacon towers of note at all. All was soon to

undergo major improvement in these areas at the behest of one of China’s

heroes named Qi Jiguang who became the principal architect of the Great

Wall in its iconic modern image of the grandest of designs. With an

upbringing which indoctrinated discipline, loyalty, martial arts,

philosophy and dedication Qi, at the age of forty, was entrusted with

the duty to reinforce the northern wall to a military standard against

the perceived northern savages. Embracing his assignment with

enthusiastic zest Qi knew exactly how and what he was intending to

achieve but as has been the custom from time immemorial the Imperial

Treasury forced him to rein in his grandiose ideas with his desired

3,000 forts reduced to 1200 of which only 1017 were actually built. Any

appeals for urgency to construct Qi’s reinforcements greatly dissipated

after the treaty with Altan in 1571. Nevertheless the resourceful

soldier was able to exploit the paranoia of the bureaucratic officials

convincing them that there was no better time to prepare for war than

during peace time so the substantial construction scheme was allowed to

carry on in earnest. Finally taking around ten years to come to fruition

Qi had ultimately succeeded in facing the existing Qin Wall with bricks

and stone while turning the top of the structure into a paved roadway or

trafficable stepped areas where slopes became too inclined. This roadway

was to be crenellated for protection while under assault as well as

being punctuated with forts standing on blocks 10 to 15 metres (3-4

storeys) above the Wall itself each accommodating up to 50 men together

with food and ammunition. Qi’s Great Wall was a fully self-contained

interactive defensive network which was never actually subjected to any

engagements to practically test its effectiveness so the Chinese legend

had created the future symbol of China without realising that it would

never be utilised for the purpose for which he had so systematically

devised it. As can be seen from the map of the Ming Dynasty this

magnificent Great Wall creation did indeed follow the northern boundary

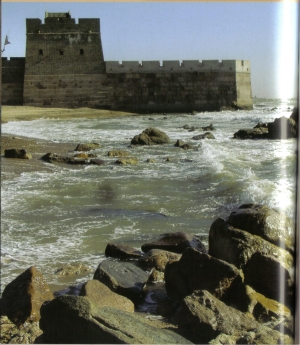

of the territorial limits of the Ming Empire easterly as far as the

ocean at Shanhaiguan.

|

Fig. 9 (left) Qi Jiguang’s statue proudly standing within

view of his greatest project – The Great Wall

Fig 10. (right) The Ming Empire 1368-1644 |

|

For a long period after the Manchu conquest of the

Mings in 1644 the dynasty known as the Qing once again subjected the

Great Wall to abject neglect and inattention right up until 1911 being

over 260 years of the abrogation of required maintenance. Even between

1911 and 1949 there was a negligible effort to restore China’s iconic

symbol of the nation’s historical accomplishments. It was left to the

Communists from 1949 until the current day to set about an extensive

renovation of Qi’s magnificent edifice. Through the very recent actions

of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage not only has the wall

been refurbished but two more areas at Huanghuacheng and Hefangkou have

been prepared for touristic inspection to provide even greater

accessibility to this marvel of Chinese civil construction. Both of the

existing viewing sites at Badaling and Mutianyu have also been upgraded

in the latest improvements to further demonstrate China’s enthusiasm to

show off their legendary monument to the rest of the world.

|

|

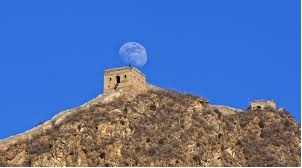

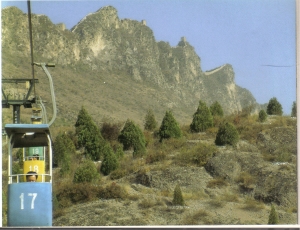

| Fig. 11 THE GREAT WALL

FROM THE SKY

...TO THE SEA |

|

CONCLUSION

My journey of discovery into the surveyors of ancient

China combined with the fascinating epic tale of the history of the

Great Wall of China has given me an incredible appreciation for the

brilliance of the great surveyors and engineers of the Imperial Eastern

civilization. My Homeresque revelation of the mythological figures of

Chinese folklore whose symbols were to become the future measuring

devices for the surveyors of yore was most exciting and very surprising

along with the amazing echelons of mathematics and measurement that were

achieved by this covert culture.

REFERENCES

Harrison-Hall, Jessica, The British Museum Pocket

Timeline of China, (The

British Museum Press, Malaysia 2008)

Man, John, The Great Wall – The extraordinary history

of China’s wonder of

the world, (Bantam Books, Transworld Publishers, London 2009)

Swetz, Prof. Frank J., The Sea Island Mathematical

Manual: Surveying and

Mathematics in Ancient China, (Pennsylvania University

Press, USA 1992)

JOHN BROCK CURRICULUM VITAE 2014

Private land surveyor since 1973, Bachelor of

Surveying from Uni. of NSW (1978), MA from Macquarie Uni., Sydney

(2000). Now Director of Brock Surveys at Rosehill (near Sydney). Papers

presented all over world inc. Egypt, Germany, France, Hong Kong, Canada,

Brunei, New Zealand, Greece, UK, USA, Israel, Sweden, Morocco, PNG,

Italy and Nigeria. Since 2002 regular column Downunder Currents in Royal

Institute of Chartered Surveyors magazine (London) Geomatics World.

Institution of Surveyors NSW Awards – Halloran Award 1996 for

Contributions to Surveying History and 2002 Professional Surveyor of the

Year. Contributor to FIG Institution for the History of Surveying and

Measurement awarded FIG Article of the Month March 2005 for “Four

Surveyors of the Gods: XVIII Dynasty of New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1400 BC)”

and FIG Article of the Month January 2012 for “Four Surveyors of Caesar:

Mapping the World.” First international Life Member of the Surveyors

Historical Society (USA), Life Member of Rundle Foundation for Egyptian

Archaeology and Parramatta & District Historical Society, Foundation

Member Australian National Maritime Museum and Friends of the National

Museum of Australia, Member of RAHS, National Trust of Australia, Hills

District Historical Society, Prospect Heritage Trust, International Map

Collectors Society and Friends of Fishes (Canowindra).

CONTACTS

John Francis Brock

P.O. Box 9159,

HARRIS PARK NSW 2150, AUSTRALIA.

Tel: 0414 910 898 Fax: +61 (0)2 9633 9562

E-mail:

brocksurveys@bigpond.com

|