| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 41

Capacity Assessment in Land Administration

Stig Enemark, Denmark, and Paul van der Molen, the Netherlands

Contents

Foreword

Executive Summary

1. Introduction

2. What Is Capacity Assessment?

2.1 Capacity Building

2.2 Levels and Dimensions of Capacity Building

2.3 Capacity Development

2.4 Capacity Assessment

3. Basic Land Administration Principles

3.1 Definitions of Land Administration (LA)

3.2 Developing a logical framework for capacity assessment in

land administration

4. Methodology

5. Self Assessment Guidelines

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Land Policy Framework ('what does LA do')

5.3 Institutional Infrastructure ('how is LA organized')

5.4 Human Resources and Professional Competence ('who carries out

LA')

Bibliography

Orders for printed copies

This FIG Guide is facing the widely stated problem of poor institutional

capacity of land administration agencies in many developing and transition

countries. Responding to this problem is not simple. The challenges of

building capacity in land administration are immense and not similar to just

human resource development. Capacity building must be seen as a broader

concept of building the ability of organisations and individuals to perform

functions effectively, efficiently and sustainable.

The Guide aims to function as a basis for improving existing land

administration systems through in-country self-assessment of the capacity needs

especially in developing and transition countries where the financial resources

often are limited. The government may form a group of experts to carry out the

analysis, as a basis for political decisions with regard to any organisational

or educational measures to be implemented for meeting the capacity needs.

The research behind this publication was initiated and funded by the Food and

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FIG and FAO hope that this

Guide can contribute to developing effective and efficient land administration

infrastructures especially in developing and transition countries in support of

poverty reduction, economic growth, good governance, and sustainable

development.

Stig Enemark

FIG President |

Paul Munro-Faure

Chief, Land Tenure and Management Unit

FAO |

Land administration covers a number of functional areas in relation to

governing the possession and use of land. It comprises a range of systems

and processes to administer land rights, land valuation and taxation, and

existing and future land use. Land administration systems are concerned with

the social, legal, economic and technical framework within which land

managers and administrators must operate.

This Guide addresses the ability/capacity of land administration systems at

the societal and institutional level as well as the individual level in terms of

professional competence and human resource development. The guidelines are

developed to serve as a logical framework for addressing each step in the

process of building adequate land administration systems - from land policy,

policy instruments, and legal framework; over mandates, business objectives, and

work processes; to needed human resources and training programs. For each step

the capacity of the system can be assessed and possible or needed improvements

can be identified.

This FIG Guide attempts to provide some practical guidance in addressing the

capacity needs. The first part of the Guide provides a general understanding of

the capacity building concept. It is emphasised that even if the key focus may

be on education and training, to meet the short and medium term needs, capacity

building measures should be addressed in a wider context of developing

institutional infrastructures for implementing land polices in a sustainable

way.

The second part of the Guide presents a methodology for an in-country

self-assessment of capacity needs and some suggestions for addressing these

needs. The methodology is based on a three stage approach by addressing firstly

the national land policy framework (the societal level), secondly the

institutional infrastructure (the organizational level), and finally the human

resources and competences (the individual level). The guidelines are presented

in the form of boxes with relevant questions to be analysed for assessing and

addressing the capacity needs.

It is of course recognised that individual countries are facing specific

problems that may not have been addressed in these guidelines at all. Hence, the

guidelines are meant as a tool for undertaking a structured and logical analysis

of the capacity needs.

In short, the guidelines are designed to pose the right questions in a

structured way rather than giving all the right answers.

1. Introduction

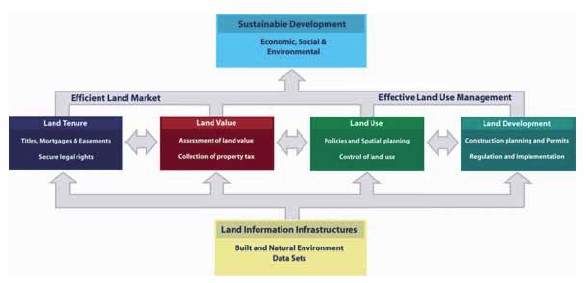

All countries have to deal with the management of land. They have

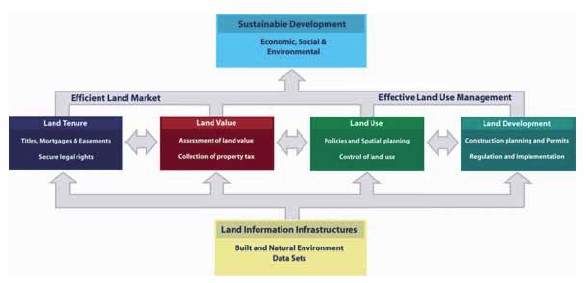

to deal with the four functions of land tenure, land value, land use, and land

development in some way or another. National capacity may be advanced and

combine the activities in one conceptual framework supported by sophisticated

ICT models. More likely, capacity will involve very fragmented and basically

analogue approaches. Different countries will also put varying emphasis on each

of the four functions, depending on their cultural basis and level of economic

development.

The operational component of any land administration system are

the range of land administration functions that ensure proper management of

rights, restrictions, responsibilities and risks in relation to property, land

and natural resources. These functions include the processes related to land

tenure (securing and transferring rights in land and natural resources); land

value (valuation and taxation of land and properties); land use (planning and

control of the use of land and natural resources); and, increasingly important,

land development (implementing utilities, infrastructure and construction

planning). The functions interact to deliver overall policy objectives, and they

are facilitated by appropriate land information infrastructures that include

cadastral and topographic datasets.

There are two key aspects in building such land administration

infrastructures: first the establishment of the appropriate land administration

system itself; and secondly ensuring that there is a sustainable long-term

capacity of educated and trained personnel in both the public and the private

sector to operate the system. In many developing and transition countries this

second aspect of human resource development is often the weakest link. However,

it is important to emphasise that capacity building must be seen in a wider

context of providing the ability of organisations and individuals to perform

functions effectively, efficiently and sustainable. This includes the need to

address capacity needs also at institutional and even more broadly at societal

levels.

This logical framework for capacity assessment is presented in a

number of boxes posing the relevant questions that should enable assessment of

the capacity needs. In total 17 boxes are presented that in a practical way

should reveal both the strengths and weaknesses of the system. The analysis may

lead to the need for organizational changes or improvements. The analysis may

also indicate the need for developing the necessary human resources and skills

base or for improving the competence of the existing personnel.

Identified needs can then be addressed within available resources

of the individual country.

2. What Is Capacity Assessment?

2.1 Capacity Building

“Capacity can be defined as the ability of individuals and

organizations or organizational units to perform functions effectively,

efficiently and sustainable.” (UNDP, 1998). This definition has three

important aspects: (i) it indicates that capacity is not a passive state but is

part of a continuing process; (ii) it ensures that human resources and the way

in which they are utilized are central to capacity development; and (iii) it

requires that the overall context within which organizations undertake their

functions will also be a key consideration in strategies for capacity

development. Capacity is the power of something – a system, an organization or a

person to perform and produce properly. Capacity Building is seen as

two-dimensional: Capacity Assessment and Capacity Development, as

presented in section 2.3 and 2.4 below.

2.2 Levels and Dimensions of Capacity Building

Capacity Building relates to three levels: society level,

organizational level and individual level. These levels relate to their

application of capacity in society and have been identified as follows (UNDP,

1998):

-

The broader system/societal level.

The highest level within which capacity initiatives may be cast is the

system or enabling environment level. For development initiatives that are

national in context the system would cover the entire country or society and

all subcomponents that are involved. For initiatives at a sectoral level,

the system would include only those components that are relevant.

-

The entity/organisational level.

An entity may be a formal organization such as government or one of its

departments or agencies, a private sector operation, or an informal

organization such as a community based or volunteer organization. At this

level, successful methodologies examine all dimensions of capacity,

including its interactions within the system, other entities, stakeholders,

and clients.

-

The group-of-people/individual level.

This level addresses the need for individuals to function efficiently and

effectively within the entity and within the broader system. Human Resource

Development (HRD) is about assessing the capacity needs and addressing the

gaps through adequate measures of education and training.

Strategies for capacity assessment and development can be focused

on any level, but it is crucial that strategies are formulated on the basis of a

sound analysis of all relevant dimensions. It should also be noted that the

entry point for capacity analysis and development might vary according to the

major focus point. However, it is important to understand that capacity building

is not a linear process. Whatever is the entry point and whatever is the issue

currently in focus, there may be a need to zoom-in or zoom out in order to look

at the conditions and consequences at the upper or lower level(s).

2.3 Capacity Development

Capacity development is a concept which is broader than

institutional development since it includes an emphasis on the overall system,

environment and context within which individuals, organizations and societies

operate and interact. Even if the focus of concern is a specific capacity of an

organization to perform a particular function, there must nevertheless always be

a consideration of the overall policy environment and the coherence of specific

actions with macro-level conditions. Capacity development does not, of course,

imply that there is no capacity in existence; it also includes retaining and

strengthening existing capacities of people and organisations to perform their

tasks.

2.4 Capacity Assessment

Capacity Assessment or diagnosis is an essential basis for the

formulation of coherent strategies for capacity development. This is a

structured and analytical process whereby the various dimensions of capacity are

assessed within a broader systems context, as well as being evaluated for

specific entities and individuals within the system. Capacity assessment may be

carried out in relation to donor project e.g. in land administration, or it may

be carried out as an in-country activity of self-assessment. This paper provides

some basic guidelines for self-assessment of the capacity needs in the area of

land administration. The guidelines attempt to address the capacity of the total

land administration system, at societal, institutional and individual level.

3. Basic Land Administration Principles

3.1 Definitions of Land Administration (LA)

FAO defines land administration as “'the way in which the rules

of land tenure are applied and made operational”. It comprises an extensive

range of systems and processes to administer the

-

Holding of rights to land (allocation, delimitation,

transfer, disputes)

-

Economic aspects of land (gathering revenues valuation,

disputes)

-

Control of land use (regulation, land use planning, disputes)

There are more definitions of land administration. In the UN/ECE

Land Administration Guidelines (1996) land administration is defined as the

“process of determining, recording and disseminating information about the

ownership, value and use of land when implementing land management policies”.

Dale & McLaughlin (1999) define land administration as “the processes of

regulating land and property development and the use and conservation of the

land, the gathering of revenues from the land through sales, leasing, and

taxation, and the resolving of conflicts concerning the ownership and use of

land”.

Whatever the case, the definitions share at least certain common

functions. These are shown in the diagram Figure 1 below:

Figure 1. A Global Land Administration Perspective (Enemark, 2004).

Land administration is considered to include a core parcel based

cadastral and land registration component, multi-purposed cadastres and/or land

information systems. Many land administration systems also facilitate or include

information on land use planning and valuation/land taxation systems – although

land administration does not usually include the actual land use planning and

land valuation processes.

The operational component of the land management paradigm is the

range of land administration functions that ensure proper management of rights,

restrictions, responsibilities and risks in relation to property, land and

natural resources. These functions include (Enemark 2004):

-

Land Tenure: the allocation and security of rights in

lands; the legal surveys to determine the parcel boundaries; the transfer of

property or use from one party to another through sale or lease; and the

management and adjudication of doubts and disputes regarding rights and

parcel boundaries.

-

Land Value: the assessment of the value of land and

properties; the gathering of revenues through taxation; and the management

and adjudication of land valuation and taxation disputes.

-

Land-Use: the control of land-use through adoption of

planning policies and land-use regulations at national, regional/federal,

and local levels; the enforcement of land-use regulations; and the

management and adjudication of land-use conflicts.

-

Land Development: the building of new infrastructure;

the implementation of construction planning; and the change of land-use

through planning permission and granting of permits; and the distribution of

developing costs.

Inevitably, all the functions are interrelated. The

interrelations appear through the fact that the actual conceptual, economic and

physical uses of land and properties influence land values. Land values are also

influenced by the possible future use of land determined through zoning, land

use planning regulations, and permit granting processes. And the land use

planning and policies will, of course, determine and regulate future land

development.

The modern land administration system acts within adopted land

policies that define the legal regulatory pattern for dealing with land issues.

It also acts within an institutional framework that imposes mandates and

responsibilities on the various agencies and organisations. As such it should

service the needs of both the individual and the community at large. As a result

the system acts as a kind of backbone in society since it is the key to

administering the relationship of people to land. Benefits arise from efficient

land administration through its role in guarantee of ownership, security of

tenure and credit; facilitating efficient land transfers and land markets;

supporting management of assets; and providing basic information and efficient

administrative processes in valuation, land use planning, land development and

environmental protection. A Land Administration System designed in this way

forms a backbone for society and is essential for good governance because it

delivers detailed information and reliable administration of land from the basic

foundational level of individual land parcels to the national level of policy

implementation.

3.2 Developing a logical framework for capacity assessment

in land administration

The land administration activity is never an end in itself, but

operates within a certain context of land policy, land management and good

governance. The justification for paying attention to land administration is to

be found in its application in the field of providing security of tenure,

regulating the land markets, levying land tax, planning and control of land use,

land reform etc. From a financial point of view this will mean that the

investments and costs of a land administration system should be justified by

macro-economic factors (like the importance of land market transactions;

industrial and agricultural development towards economic growth; and

environmental sustainability of land and natural resources) and micro-economic

factors (such as land as a collateral for micro credit for households and small

businesses; paid mortgage interests that underpin the financial institutions;

and paid land taxes that underpin public services).

To put it briefly: capacity needs in land administration are

highly influenced by the way governments want to administer the land, and also

by the way regulations and organisations are implemented and managed within the

country.

It emanates from the earlier given definitions of land

administration that governments pursue political objectives of which many are

land related, such as poverty eradication, sustainable agriculture, sustainable

settlement, development of economic activity, and strengthening the role of

vulnerable groups within the society. In order to realise these objectives

governments could develop a policy on how the land ('access to land') and the

benefits of the land ('access to land related opportunities') are to be

allocated. With the aim of implementing such policies governments define how

they want to regulate land related activities in society, such as holding rights

to land, economic aspects of land, and control of land use and development.

For this, the government needs a mandate. Therefore the

government promulgates laws and prescriptions to legitimize these regulations

within the three areas of holding rights to land, control of land use, and

economic aspects of land:

-

Regarding the issue of 'holding rights to land', the rules

and prescriptions define the mode in which rights to land can be hold

(customary law, land law), who will have access to holding rights to land

(land reform), through which mechanisms people can acquire rights to land

(e.g. sale, lease, loan, gift, inheritance, allocation by chief), how

security of tenure can be guaranteed (customary traditions, land

registration system and cadastre), how land disputes are to be adjudicated

(customary traditions, civil or administrative law).

-

Regarding the issue of 'economic aspects of land', the rules

and prescriptions define how the government might levy taxes on land (land

taxation), through which mechanisms the tax base might be assessed (land

valuation), and how disputes might be adjudicated (administrative law).

-

Regarding the issue of 'control of land use', the rules and

prescriptions define how the government might regulate the use of land and

its resources (planning control, subsidies, permits, management of state

lands, customary traditions), through which mechanisms the government will

have the competence to interfere in private rights to land (planning law,

public acquisition of land, expropriation), and how disputes are to be

adjudicated (customary traditions, administrative law).

In order to implement the rules and prescriptions the government

assign mandates within the public administration regarding the tasks to be

carried out. This includes policies on centralization/decentralization,

public/private roles, customer orientation, public participation,

accountability, liability, and good governance in general. In order to exert the

given mandate, the organizations have to define their business objectives, work

processes, ICT policy, quality management procedures, and their relationships

with other organizations e.g. by means of spatial data infrastructures. (van der

Molen, 2003b).

In order to make the organizations work they have to identify the

staffing policy, the required expertise and skills (education and training

analysis), and the tools for educational development such as education and

training programs and opportunities for continuing professional development.

By consequence, basic principles for land administration capacity

are as follows:

-

Policies and a legal framework that define the private and

public status of land in terms of tenure, value, and use.

-

Mandates allocated to the public administration in order to

establish transparent and viable institutions.

-

Organisations that are empowered to meet the societal demands

at lowest possible costs in order to optimize the support to land tenure

security, land markets, land use control, management or natural resources,

land reform and other land related social structures

-

Managers and employees who are empowered to meet individual

demands in terms of skills and professional competence for working efficient

and effective.

-

Businesses and citizens, who are empowered to participate

effectively in order to comply with the land related social arrangements.

4. Methodology

As already stated above, capacity building is not similar to just

human resource development. It addresses the broader concept of the ability of

organisations and individuals to perform functions effectively, efficiently and

sustainable. The logical framework developed in section 3.2 above may then be

organized into specific steps that can be considered as building blocks in the

Guidelines on Capacity Assessment in Land Administration.

This should not be done in a normative way. Research reveals that

because of the very nature of land administration systems no systems can be

designated as “the best”. As explained in section 3.2 above, land administration

systems have to serve certain functions in society, as they are defined by the

same society given its own policy, jurisdiction, history, and national and local

culture.

Therefore, the specific steps should serve as a guideline for

countries which are ambitious to assess, in logical way, the capacity of their

existing land administration system in order to identify any needs for

improvements in terms of organisational or educational measures.

The guidelines will then serve as a logical framework for

addressing each step from land policy, policy instruments, and legal framework;

over mandates, business objectives, and work processes; to needed human

resources and training programs. For each step the capacity of the system can be

assessed and possible or needed improvements can be identified.

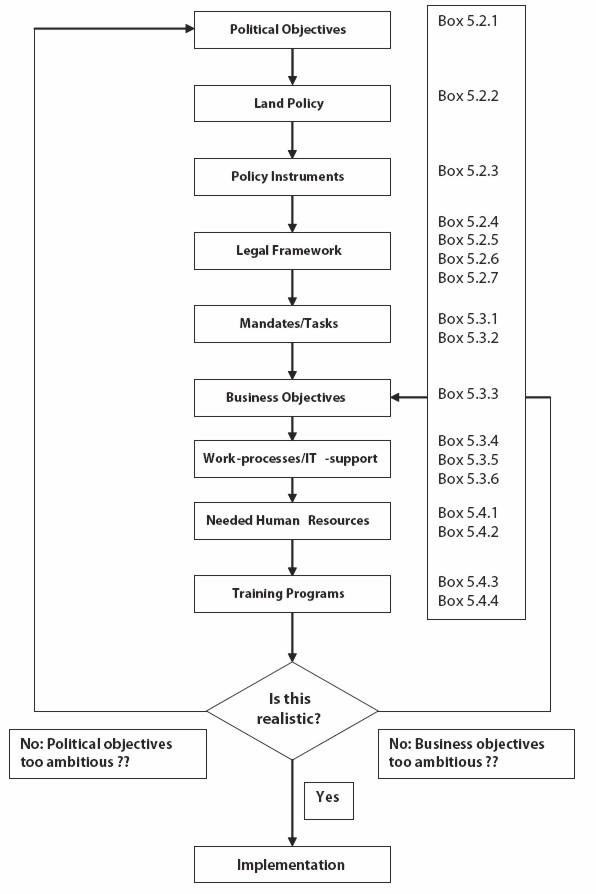

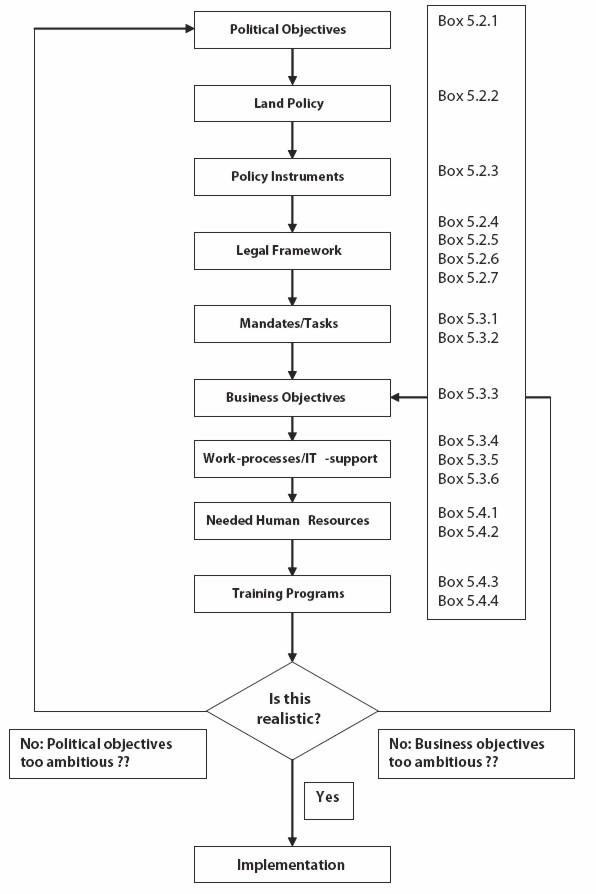

The steps are identified in the logical framework presented in

figure 2 below. Each step is then addressed in a box posing some key questions

to be analyzed. Some comments are given in each box in order to facilitate the

analysis. The analysis may lead to the need for organizational changes or

improvements. The analysis may also indicate the need for developing the

necessary human resources and skills base or for improving the competence of the

existing personnel.

The analysis must of course be realistic. For example if a

country such as Indonesia wished to have a land administration system supported

by a land title and cadastral surveying system similar to Denmark or Australia,

this could possibly require 40,000 professional land surveyors and 30 or more

university programs educating professional surveyors (based on Steudler et. al.,

1997). Clearly this is not realistic even in a medium term perspective. As a

result, there is a need to develop appropriate solutions matching the stage of

development and specific characteristics and requirements of the individual

country.

Therefore, the analysis may lead to adjustment of the political

objectives and/or adjustment of the business objectives for the individual

organizations. This is shown in the diagram below. It should be stressed that

the methodology is mainly aiming at developing and transition countries.

Figure 2. A logical framework for self-assessment of

capacity needs in land administration

5. Self Assessment Guidelines

5.1 Introduction

The guidelines are presented as a number of boxes following the

logical framework presented in section 4 above. The guidelines aim to function

as a basis for in-country self-assessment of the capacity needs in land

administration. The government may form a group of experts to carry out the

analysis, as a basis for political decisions with regard to any organisational

or educational measures to be implemented for meeting the capacity needs.

5.2 Land Policy Framework ('what does LA do')

5.2.1 Political Objectives

What are the political objectives that relate to access to land

and land related opportunities?

- Is the government well aware of the importance of the land issue

for sustainable development?

- Is it recognised that land is a key issue in terms of political

objectives?

Comments:

In many global documents such as Agenda21 and other UN, FAO and

Habitat declarations land is considered as crucial issue. Main political

objectives such as poverty eradication, sustainable housing and

agriculture, strengthening the role of vulnerable groups (indigenous,

women), are one way or another related to access to land, and to

land-related opportunities. This definitely impacts on the policy of

donor agencies (e.g. the English policy on 'better livelihoods for

people', the German policy on 'land tenure in development cooperation',

and the Dutch policy on 'business against poverty'), and on Poverty

Reduction Strategy Papers for the World Bank.

Land policy could be defined as the way governments deal with the

land issue. It is within this context that we can identify the function

of land administration systems, as a supporting tool to facilitate the

implementation of a proper land policy in the broadest sense.

Impact on capacity:

Linking land administration systems to political objectives promotes

good business focus for land administration organizations, and provides

a justification for investments in establishment, maintenance, and good

governance |

| |

5.2.2 Land Policy

Are the political objectives well expressed in the current land

policy?

- Does the land policy address the key issues?

- Is the access to land, the allocation of land, and the resulting

land use in conformity with the political objectives?

Comments:

Governments should develop a policy on how the land ('access to

land') and the benefits of the land ('access to land related

opportunities') are to be allocated. With the aim to implementing this

policy governments define how she wants to regulate land related

activities in society, such as holding rights to land, control of land

use, and economic aspects of land.

Access to land and land related opportunities can be approached in

different ways, for example from the point of view of equality of land

distribution, or encouraging viable farming through imposing a minimum

size of the holdings, or combating large holdings through enforcing

ceilings of land ownership, etc. Access to land can also be through the

rental market, which is especially applicable in urban areas, but also

in rural areas in the form of short leases. Access to land is not only a

matter of having the opportunity to benefit from land. Important is that

this should be possible in a sustainable way; therefore the security of

tenure plays a key role.

Impact on capacity:

If the way the government wants to allocate the land and the benefits

of the land is clear, it provides focus to land administration

activities, which will enhance their ability/capacity to fulfil the

political objectives. |

| |

5.2.3 Policy Instruments

Which instruments are at the disposition of the government to

regulate the land related activities in society regarding:

- The whole complex of holding rights to land?

- The whole complex of planning, development and control of land

use?

- The whole complex of land valuation and taxation for gathering

revenues?

Comments:

Governments have to identify which instruments they want to apply in

order to implement the political objectives and the way of allocating

land and the benefits of land. If a government aims at providing its

citizens with very secure title to land, it should for example put an

adequate title registration system in place. If the government wants to

control land use, e.g. there should be a system of land-use approvals

through permits. If governments want to redistribute land ownership,

e.g. there should be a land reform policy in place combined with

mechanisms for acquisition and distribution. If a government wants to

control the land market, there should be measures of a market

regulation. Briefly: policy objectives and the 'how to do' question go

together.

Impact on capacity:

A good link between objectives and instruments provide a good

starting point for the clarification of user requirements for land

administration systems and thereby the ability/capacity of systems. |

| |

5.2.4 Legal Framework – General

Does the legal framework provide sufficient legitimization of the

government's regulations?

- To which extent does the framework meet the demands of the rule

of law, e.g. the constitutional law?

- Is the issue of public consultation well addressed in the

procedural rules?

Comments:

Governments are expected to work within the principles of good

governance and the rule of law. Good governance is normally defined as

'the way power is exercised in managing a country's economic and social

resources for development'. This includes five major elements:

effectiveness of the law making process; existence of mechanisms for

mobilizing public support; effectiveness of the management of the public

sector; effectiveness of the enforcement of the law; and existence of

appeal procedures.

The Rule of Law can be defined to exist when there are measures for

peaceful solution of disputes based on law rather than on force, and

measures for controlling the government itself through limitations of

official power by a variety of legal mechanisms, both substantive and

procedural (Moore, J.B., University Virginia). There are five major

elements: guarantee of basic rights; separation of powers; legality of

the administration; constitutionality of laws; judicial remedies and

judicial review.

Impact on capacity:

A legal framework that legitimizes governmental actions also provides

a legally meaningful land administration system, and enhances its use. |

| |

5.2.5 Legal Framework – Land Rights

Does the legal framework provide enough clearness and transparency

regarding the whole complex of holding rights to land?

- Are the rights people might have to land (including role of

customary law) sufficiently transparent?

- Is it clear who has access to obtaining rights to land?

- Do the regulations address the equity and fairness on access to

rights to land (land reform)?

- Are the procedures for establishment, transfer and abolition of

rights to lands clear and well accepted?

- Do the regulations for the land market serve equity and fairness

without moving people in illegality or informality?

- Is security of tenure provided and to which extent (land

registration, titles, cadastres, conveyance procedures)?

- Are there appropriate means for conflict resolution in place

(courts, mediation, traditional means)?

- Can legal and administrative arrangements enforce these issues

in a way that comply with good governance and the rule of law?

Comments:

The latest definition land registry and cadastre is from Kaufmann &

Steudler in 'Cadastre 2014' (1998, saying it is 'a methodically arranged

public inventory of data concerning all legal land objects in a certain

country or district, based on a survey of their boundaries; such legal

land objects are systematically identified by means of some separate

designation; they are defined either by private or public law; it

contains the official records of rights to legal land objects'. This

definition is building upon earlier definitions for example by the

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG, 1995).

Important is that land administration systems, which exist in the

first place of land registers and a cadastre, are based on legally

recognised rights and interest in land. Such systems therefore flourish

if there is enough clarification on the nature and form of lands rights,

procedures for establishment, transfer and abolition etc. Regarding the

earlier mentioned policy objectives (box 1 above), these should be

reflected in the way rights to land is defined, and how procedures for

holding rights in land are designed.

Impact on capacity:

The existence of an adequate legal framework for land rights that

meets the demands of society, enterprises and individuals will enhance

the ability and capacity of the land administration system to serve

society needs. |

| |

5.2.6 Legal Framework – Land-Use

Is the whole complex of planning, development and control of land

use well defined and enforced?

- Is there a policy at various government levels clarifying about

how to use the land?

- Is the relationship between planning, development and control of

land use well defined?

- Is it clear how the government might interfere in private rights

to dispose of their land?

- Are there enough opportunities for the government to acquire

private land for public development purposes?

- Are the rules for the governmental management of state lands

clear and adequate?

- Are there enough legal and administrative arrangements to

enforce these issues in a way do they comply with good governance

and the rule of law?

Comments:

Governments tend to exert a certain control to the development of

space in the country. In extreme form this might occur by declaring all

landownership to the state and allowing land use according to the

government's decisions only. The government in any case has to decide to

which extent she wants to have control over land use. This requires

regulations defining the way these powers might be exerted.

For example, the legal meaning of zoning plans should be clear. In

what way are they binding to the citizen, and are they binding to the

government itself? If citizens do not comply with the land-use

regulations, how can the government enforce the regulations and

interfere in private rights to land? This is even more demanding in

situations where the government may want public acquisition of land,

through pre-emptive rights and expropriation. Planning, development and

control are, this way, interrelated components of land use control.

Impact on capacity:

Referring to earlier definition of land administration (UN/ECE,

1996), it was said that land administration provides the context for

determining, recording, and disseminating information about ownership,

value and use of land when implementing land management policies. The

existence of an adequate legal framework for land planning and land use

rights will enhance the ability and capacity of the land administration

system to serve society needs from both the government and the citizen

perspective. |

| |

5.2.7 Legal Framework – Land Value

Is the whole complex of valuation and taxation of land for

gathering revenues well defined and enforced?

- Can land be used as a tax base?

- Is the impact of taxation on the use of land and land markets

taken into account?

- Do the valuation methods fit to the societal needs?

- Do the people comply with the rates that convert land value into

the levied tax amount?

- Are there legal and administrative arrangements in place to

enforce these issues in a way responding to good governance and the

rule of law?

Comments:

Land taxation is considered as a major source of income especially

for local governments. Four aspects are of importance: who is the

taxpayer; what kind of land and property is the land to be taxed; what

is the valuation mechanism; and what is the rate to be levied based on

this information.

The balance between income tax and land tax should be carefully

considered and the procedures and efforts invested in the land

valuation/taxation procedures should be balanced against the revenue

gained through taxation of land and property.

Major valuation mechanisms are based on an assessment of the market

value of the property. This means that the system should provide the

most important basic information regarding the taxpayer, the taxable

land, and the taxable value. This also goes for countries where the land

tax is based on some form of what is called cadastral income (as a kind

of estimate of the benefit one could reap from the property).

Impact on capacity:

Clearness about valuation procedures, land taxation laws, and the

authorities will contribute heavily to the ability/capacity of the land

administration system. |

5.3 Institutional Infrastructure ('how is LA organized')

5.3.1 Allocation of Mandates - General

Are the mandates in place for exertion of land related legal

framework?

- Are the mandates overlapping?

- Are the mandates clear and manageable?

Comments:

Clear mandates within the public administration enhance the

effectiveness. There are countries where various organisations have a

mandate on land related issues (for example the issuing of land titles).

This is not only causing frictions in the public administration, but

moreover also confuses the citizens. Governments should take into

account the operational aspects of the mandate. It makes no sense to

impose a mandate that is expected not to be workable and manageable.

Impact on capacity:

The ability/capacity of any land administration system relies on

clear mandates. Without a clear and manageable mandate, good performance

can never be guaranteed. |

| |

5.3.2 Allocation of Mandates - Decentralisation

Does the allocation of mandates reflect a well-balanced approach

to decentralisation?

- Are the linkages between the mandated organizations well defined

to ensure good institutional co-operation?

Comments:

Land administration is often associated with decentralization. The

reason is that decisions on land very much affect ordinary people, and

therefore it is efficient and effective to allocate these tasks at the

appropriate local level of government. In allocation of tasks at that

specific level, the need for sharing information should be taken into

account. E.g. application of information technology can provide a system

of central processing and storage, and local information management.

Impact on capacity:

The ability of land administration organisations should on one hand

reflect the importance of local presence, on the other hand guarantee

countrywide application. This balance is important to meet customer

demands. |

| |

5.3.3. Business Objectives - Customer Orientation

Are the business objectives for mandated organisations clear and

specific?

- Does the mandate include meeting the demands of the customers

and other stakeholders?

- Is there a clear policy in place for the management of customer

relations?

Comments:

Implementing a mandate is one thing, doing it in a customer friendly

way is another. Many government organizations seem to believe that good

customer orientation is not relevant for them, because they perform a

public task. On the other hand it could be argued that exerting a public

monopoly includes even more attention to customers than in commercial

business, as the customers of public organizations normally don’t have a

choice. Dissatisfaction will be their basic attitude.

To push government organizations forward towards customer

friendliness, it might be advised to include ‘customers’ in their

mandate, or in the derived mission statement.

Maintaining good relationships with customer’s urges for good market

communication such as telling the customer what he can expect and

thereby avoiding over-expectations. This may sound very commercial, but

if -for example- land registers and cadastral maps are in digital

format, these databases could provide many sorts of land information,

both standards- and customized products that can be electronically

accessed, making helpdesks necessary, call centres, product folders,

complaints procedures etc. If customers have to pay a certain price for

a product, they require financial transparency, especially in the case

of government organizations. In the commercial environment this is less

important, as customers can go to the competitor if they are unsatisfied

by the performance of a company.

Impact on capacity:

Customer orientation requires a certain amount of dedicated staff,

with specific expertise and skills. |

| |

5.3.4 Work Processes

Are the work processes for realization of the mandate well defined

and manageable?

- Are the work processes monitored and evaluated?

- Is the organizational structure well designed for the execution

of the work processes?

- Is there a policy in place for design of spatial data

infrastructures at national and local level?

Comments:

Having good control of the organization’s performance is impossible

without a clear description of work processes, in terms of activities,

requirements and responsibilities. This is the basis for monitoring and

accountability. At the same time a clear description offers

opportunities to identify and abolish inefficiencies. Processes in the

field of land management often tend to be very complicated and

bureaucratic. The lack of transparency regarding procedures in, for

example, the areas of land titling, the land market, and land use

control is often mentioned as a main source for cumbersome operations.

Therefore, talking about capacity in the sense of ability, the

capacity of organizations to deliver is at stake. From the management

point of view, the way of monitoring of work processes is important.

During the process itself the key steps should be evaluated, in order to

identify bottlenecks and delays.

Sound land administration also requires support from a well-developed

spatial information infrastructure for sharing geo-referenced

information at national and local level. This includes the need of

adequately to address conceptual and policy issues such as data access,

intellectual property, cost recovery, and design of an efficient

institutional framework.

By creating an infrastructure and the relevant linkages positive

results will emerge. Clear responsibility for data maintenance and

upgrade will be established, duplication will be reduced and analysis

improved. Sound decision-making processes are developed for governments

at all levels, and valuable information is created for academic

institutions, the private sector and the community (see FIG publications

no 30 and 31 on Spatial Information and Land Information Management for

Sustainable Development).

Impact on capacity:

Basically capacity is delivered through work processes. Without

appropriate attention to work processes, and the structures in which

they have to operate, the ability of organizations for a good

performance can be questioned. |

| |

5.3.5 Information and Communication Technology (ICT)

Are the ICT applications well designed to support the work

processes and the business objectives?

- Is the internal and external information flow clearly specified?

- Is the information technology sufficient for further development

and maintenance of the information system?

Comments:

Many processes in the field of the administration of land require

huge amounts of data. This is typically the case for land registration

and cadastre, but also –as examples- for monitoring the land market,

land use planning and control, land taxation, management of natural

resources and land reform.

In the case of land registration and cadastre the maintenance of

these datasets is the main challenge, as the establishment, transfer and

deletion of rights and interests to land is a continuous process

resulting in changes of the datasets at a daily bases. Without

mechanisms for maintenance, the investments in the establishment of

these datasets will soon have no return. The solution for dealing with

these high transactional datasets is the application of ICT, although

prior to the introduction of adequate ICT products many countries were

successful in keeping their datasets up to date in a manual way. It

could even be good for employment! Whatever the case, nowadays these

organizations dedicate substantial amounts of money to system design,

system development, and system operations.

It is, however, well understood that installing hardware and software

as such is not the way to fully benefit from ICT. At the contrary, it is

actually considered as the last step in the process of applying

ICT-tools. Management literature reveals a (at least) three-step

approach. Beginning with analyzing the flows of information within the

organization itself and between the organization and its external

environment (customers, other stakeholders), then analyzing which

software is suitable for good support of these flows, and then finally

the selection of hardware that suits best. In ICT-terms one says that

first of all there should be a good understanding of the ‘information

infrastructure’, before entering to the issue of ‘ICT-architecture’.

Impact on capacity:

Ability of organizations to meet their specific functions in society

requires appropriate management of ICT in the organization. Whatever

level of ICT application is at stake, this remains important. Especially

organizations that apply ICT gradually - from simple to more complex

approach - should have a sound ICT-policy otherwise it may lead to

serious problems at a later stage. |

| |

5.3.6 Good Management

Are the guiding principles for good management clear and

understandable at all governmental levels?

- Is the allocation of tasks and responsibilities to managers

appropriate and do they have the necessary power of execution?

- Are the managerial tools in terms of planning control,

accountability and liability appropriate?

- Is the system of performance monitoring appropriate?

- Are the financial mechanisms appropriate and do they meet the

business demands?

- Does the organisational culture encourage the sharing of values

towards good performance?

Comments:

Good management of organizations is about responsibility and

accountability, as this is the way people co-operate. The more functions

in the organization are spread over people, the more people are asked to

rely on the performance of the other people. The allocation of tasks and

responsibilities by consequence should be clear and transparent. Besides

it might be observed, that sometimes people have certain

responsibilities, without having the powers to exert their

responsibility properly. Allocation of tasks and responsibilities

therefore should go together with the allocation of appropriate mandates

to these people.

A related issue is the way managers administer in the sense of

planning and control. Meeting business objectives (for example:

delivering building permits based on zoning plans within e delivery time

of say 30 days) require careful planning at various levels, and control

mechanisms to guarantee delivery. In the quality management approach one

speaks about the ‘plan-do-check-act’ cycle. Embedded in the system of

clear allocation of tasks, responsibilities, powers and accountability,

this way of working forms the basic tool for managers.

Planning is not only about staff resources; it is also about money.

Being responsible for budgets requires similar mechanisms as mentioned

above. Again embedded in the allocation of tasks and responsibilities,

planning and control with respect to money is the basic tool for

financial management.

Impact on capacity:

Ability of organizations to deliver depends on the mechanisms of

planning and control to form good management. |

5.4 Human Resources and Professional Competence ('who

carries out LA')

5.4.1 Assessment of Human Resources

Is there a policy in place determining the amount of staff and

their required competences?

- Do the managers and employees know which job-categories require

which expertise and skills?

- Do the organizations know how to assess the need for qualified

personnel?

Comments:

In most developing and transition countries capacity assessment and

development in terms of human resources is considered to be the most

critical. This is about assessing the need for individuals to function

efficiently and effectively within organizations and within the broader

system, and it is about addressing the gaps through adequate measures of

education and training.

Land Administration is about people – from politicians, senior

professionals and managers, middle managers and administrators, to

office and field personnel, - whether in public or private sector. At

the senior level a broad vision and understanding is required. At the

more practical level the players in the system need to have an

understanding of the overall system but some will have much more

detailed and specific skills that need to be developed.

In order to assess the capacity needs there is a need to identify the

work processes in relation to the different land administration areas,

such as land registration, subdivision, surveying and mapping, land-use

planning and sectoral land management, land valuation and taxation. The

content of these work processes should be identified in relation to, the

legal and organisational framework for fulfilling the land policies.

Next step is to identify the personnel needed at various competence

levels to carry out the work processes. This is simply to assess the gap

between the existing capacity and the capacity needed to undertake the

land administration tasks in the short, medium and long term. The

assessment should include both the public and the private sector.

Impact on capacity:

Assessing and addressing the capacity needs in terms of human

resources is of course crucial to the ability/capacity of total the land

administration system. |

| |

5.4.2 Assessment of Educational Resources

What kind of educational and training resources are currently

available?

- Do the educational and training programs have sufficient

capacity?

- Are the educational and training programs appropriate?

Comments:

Once the capacity needs in terms of qualified personnel are

identified, the next step is to consider the ways and means to address

the gap. For the purpose a review of the current educational and

training resources is essential.

The review should include in country as well as out-of country

educational opportunities, and it should include national as well as and

local educational institutions at different levels.

The existing programs at university level should be reviewed and

assessed against the capacity needs. However, since land administration

is a very interdisciplinary area there may be any adequate educational

programs available. A new program may then be developed and hosted by a

faculty providing the right combination of professional and research

skills.

Surveying education has traditionally leaned strongly toward

engineering. A Land management approach to surveying education will,

however, need a shift to teaching management skills applicable to

interdisciplinary work situations and developing and running appropriate

systems of land administration. Surveying and mapping are clearly

technical disciplines (within natural and technical science) while

cadastre, land management and spatial planning are judicial or

managerial disciplines (within social science). The identity of an

adequate land administration program should be in the management of

spatial data, while maintaining links to the technical as well as social

sciences.

The existing programs at technician level should also be examined

against the capacity needs. These programs may, however, have a more

specialised profile to meet the needs for trained technicians in

specific fields.

The review of the current educational resources should of course

include the range of qualified teaching staff, range of equipment,

instruments and building facilities, etc.

Impact on capacity:

Sufficient and adequate educational resources are essential to

provide the professional competence required for developing and

maintaining appropriate land administration systems. |

| |

5.4.3 Means of Educational Development

What kind of educational development is needed and adequate to

address the capacity needs?

Capacity development includes a whole range of options with regard to

the design of educational programs:

- The design of in-country programs at diploma, bachelor, and

master’s level should consider the immediate short-term needs for

well-trained technicians as well as the longer term needs for

qualified professionals. The training policies should meet these

needs by adopting a modular structure to ensure flexibility, e.g.

the diploma program may be merged with the first part of the

bachelor program, and the program may allow existing personnel to be

updated and upgraded to fulfil the capacity needs. A recently

developed educational program in Malawi is an example of such a

flexible and interdisciplinary approach (Enemark and Ahene, 2003).

The programs should draw from local/regional teaching expertise to

ensure long-term sustainability.

- The design of programs at certificate level, e.g. a one-year

program aiming at training “land clerks” for the tasks undertaken by

traditional authorities such as basic land measuring and recording

related to the formalization of customary land rights.

- Sandwich and franchise programs: Such programs should be

considered to balance the lack of in-country educational capacity.

Out-of country training, and study tours abroad may also be

considered in this regard.

- Training programs may be designed for e.g. hands-on training at

the workplace. This will normally also include a program for

training the trainers.

- Continuing Professional Development (CPD): Such programs may be

designed to improve the competencies of the existing work force in

relevant areas. The programs may be developed provided by the

universities as well as by private course providers. The programs

should be developed in cooperation between the course providers and

professional practice.

- Virtual programs: This includes distant training at local,

regional, national and international level. Such programs are

normally rather expensive to develop and the provision demands a

well-established national IT-infrastructure.

- Other measures: This may include workshops, seminars, etc. to

promote understanding, debate, and analysis of land issues at the

policy, management and operational levels.

Impact on capacity:

Land administration systems cannot be developed and sustainable

maintained without an adequate and sound educational base. |

| |

5.4.4 Means of Professional Development

What kind of professional development is needed and adequate to

address the capacity needs?

Professional development in the area of land administration is a

shared responsibility of the employers, the employees, and professional

institutions, supported by the educational institutions. A range of

options are available:

- Professional institutions such as a National Association of

Surveyors play a key role in developing and enhancing professional

competence. This relates to areas such as ethical principles e.g.

through adoption of model codes of professional conduct suitable for

performing the tasks and serving the clients and the societal needs.

FIG offers some guidance in this area (FIG publication no. 16 on

Constituting Professional Associations, and no. 17 on Statement on

Ethical Principals and Model Code of Professional Conduct).

- Professional associations may adopt requirements continuing

professional development to be followed by their member in order to

maintain and enhance professional competence (see FIG publication

no. 15 on Continuing Professional Development).

- Professional associations may also cooperate on regional level

e.g. to enhance educational and professional standards, and to

facilitate mobility through means of mutual recognition of

professional competence (see FIG/CLGE, 2001 on Enhancing

professional Competence of Surveyors in Europe, and FIG publication

no. 27 on Mutual Recognition).

- Establishing a National education and research centre may be

used a means ensure sustainability and continuity, and to develop a

corporate memory of land administration experience within the

country.

- In countries where there is an on going land administration

project e.g. supported by the World Bank, the Centre could act as an

ongoing body of knowledge and experience in land administration and

using the actual project as a long-term case study and operational

laboratory. The centre could provide educational programs and

supervise establishment of educational programs at other

institutions. The centre could interact with international academics

and professional bodies to interact and assist the development of

local academics.

Impact on Capacity:

Land administration systems cannot be developed and sustainable

maintained without sound professional institutions supporting

professional development. |

Dale, P. and McLaughlin, J. D. (1999): Land Administration. Oxford University

Press

Enemark, S. (2002): The Danish Way. Ten articles presenting the professional

areas of surveying and Land Management in Denmark.

http://ida.dk/DdL/The+Danish+Way/

Enemark, S. and Ahene, R. (2003): Capacity Building in Land Management –

Implementing Land Policy Reforms in Malawi. Survey Review, Vol. 37, No 287, pp

20-30.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_2002/Ts7-7/TS7_7_enemark_ahene.pdf

Enemark, S. (2004): Building Land Information Policies. UN, FIG, PC IDEA

Inter-Rgeional Special forum on the Building of Land Information Policies in the

Americas. Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26-27 October 2004.

http://www.fig.net/pub/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf

FIG Permanent Institution: International Office of Cadastre and Land Records

(OICRF). http://www.oicrf.org/

FIG Publications no. 11, 15, 16, 17, 27, 30. FIG Office, Copenhagen.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pubindex.htm

FIG/CLGE (2001): Enhancing Professional Competence of Surveyors in Europe.

FIG and CLGE, FIG Office, Copenhagen.

http://www.fig.net/pub/CLGE-FIG-delft/report-1.htm

FIG/UN-Habitat (2002): Land Information management for Sustainable

Development of Cities – Best Practice Guidelines in City-wide Land Information

management. FIG Publication No 31. FIG Office, Copenhagen.

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub31/figpub31.htm

Kaufmann, J. and Steudler, D. (1998): Cadastre 2014. FIG/Kuhn Druck, AG

Switzerland.

http://www.fig.net/cadastre2014/

Steudler, D. et. al.(1997): Benchmarking Cadastral Systems. The Australian

Surveyor, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp 87-106.

UNDP (1998): Capacity Assessment and Development. Technical Advisory Paper

No.3.

http://magnet.undp.org/Docs/cap/CAPTECH3.htm

UN-ECE (1996): Land Administration Guidelines. UNECE, Geneva.

http://www.unece.org/env/hs/wpla/docs/guidelines/lag.html

UN-ECE (2001): Land (Real Estate) Mass Valuation Systems for Taxation

Purposes in Europe.

http://www.unece.org/hlm/documents/2002/hbp/wpla/mass.valuation.pdf

UN-ECE (2004): Guidelines on Real property Units and Identifiers. New York

and Geneva.

http://www.unece.org/hlm/wpla/publications/Guidelines%20On%20Real%20Property%20-%20FINAL.doc

UN-ECE (2005): Social and Economic Benefits of Good Land Administration.

Second edition. New York and Geneva.

http://www.unece.org/hlm/wpla/publications/UNECE%20Statement%20-%20Final%20version.pdf

UN-ECE (2005): Land Administration in the UNECE Region – Development trends

and main principles. UN, New York and Geneva.

http://www.unece.org/env/documents/2005/wpla/ECE-HBP-140-e.pdf

UN-FIG (1999): The Bathurst Declaration on Land Administration for

Sustainable Development. FIG Office, Copenhagen,

http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub21/figpub21.htm

Van der Molen, P. (2001): The importance of the institutional context for

sound cadastral information management for sustainable land policy, FIG Regional

Conference, Nairobi, 2002

Van der Molen, P. (2003a): Six proven models, FIG Working Week, Paris.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_2003/TS_11/TS11_2_vanderMolen.pdf

Van der Molen, P. (2003b): Future Cadastres, FIG Working Week, Paris.

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_2003/PS_1/PS1_3_vanderMolen.pdf

Williamson, I., Enemark, S., Wallace, J. (Eds): Sustainability and Land

Administration Systems. Proceedings of Expert Group Meeting, Melbourne,

Australia, 9-11 November 2005 (270 p.)

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/research/SDI_research/EGM%20BOOK.pdf

|